- Stephen Dodgson

- Robert Fayrfax: Missa 'Sum Henricus Octavus'

- Marcello Abbado

- John Bell Young

- Cairo

- Stephen Shellard

- Christian Immler

- Mahler Chamber Orchestra

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

WHAT HARPSICHORDISTS CAN LEARN FROM PADEREWSKI

ENDRE ANARU investigates, and offers a suggestion

Far be it from me to teach others better than myself to practice their art. But, I must draw attention to this issue lest musicians keep poking away at Music until nothing is left but wood chips and dust.

After a hundred year (or so) lacuna, the art of the harpsichord was revived in the twentieth century. The amount of research and discussion is astounding, but I fear that though many critics of historically informed performance (HIP) are on the right track: something is wrong with the results. But they can't quite figure out what it is.

Close-up photo taken by Egemen Şahin in Vienna, Austria in 2024 of an old keyboard instrument

First, we must remember that this language of harpsichord playing has been relearned without a living exemplar of its speech. No one was left alive who had heard and mastered the art of harpsichord playing before it was annihilated by the new methods and the new instrument of the fortepiano. That its sound is a little off kilter in not at all to be surprised. The question becomes:

Is there anything that can help add to the stock of knowledge that might assist resuscitating harpsichord performance into a living and breathing language?

Second, the revival of ancient music that took place after 1945 is itself a stylistic rejection of Pre-World War II musical notions, and a continuance of the rejection of nineteenth century practice. But the rejection became more and more tenuous as time passed and more and more irrelevant as the style changed, but the mind-set of the critics did not. By 1955 most keyboardists were not playing like nineteenth century pianists, and the ones that were, were either the old-timers (Egon Petri, Josef Hofmann - both of whom were sidelined by health issues), or were relegated to the back of the professional bus (like Earl Wild or Shura Cherkassky, both outstanding pianists whose careers did not properly flourish because they were practitioners of older stylistic methods. In Wild's case, it was repertoire such as Liszt operatic paraphrases and Cherkassky for his flexible approach to rhythm and layered sounds). But HIP performers have been lambasting those modern pianists who did not play in the nineteenth century fashion, as if they did. They didn't. I omit names for the sake of potential quagmires of argumentation.

I suggest that attending to very old 78rpm recordings and piano roll recordings of pianists (and certain specific ones at that) would be useful as they reveal techniques of performance that have been forgotten and are of interest because they are real expressive devices. That they are out of fashion is irrelevant.

After you cool your jets in offence at such an obviously nonsensical idea, I ask this: 'In what way can they be useful?' I follow here then the philosophical approach of pragmatism - a quintessentially American psyche construct - as exemplified by John Dewey (1859-1952). The answer to 'What is true?' is 'What works in real life'. Thus, in this hypothesis building experiment, the search is always for the useful.

Concerning the old recordings, the reason is simple: on early recordings we can hear how people spoke (that is musically spoke) before the catastrophe of 1914, before modernism, before jazz, before recording technology changed how to listen (and how to perform).

This next point is very important: I am not suggesting that these pianists represent a performance practice tradition that extends back in the remotest past (though it was always to habit of those pianists to trace their lineage: this one to Bach, another to perhaps Sweelinck). This lineage seeking fell out of favour in the twentieth century (cf insults to the Canadian Encyclopedia of Music in its first incarnation), but lineage is crucial in aristocracy, religion, and the confluence of the two (such as the Sayyids of Islam descended from the Prophet Mohamed). To ignore lineage is just folly and not the way humans actually think - hence the number of sons who follow in their father's footsteps, eg Justin Trudeau or George W Bush.

I am not suggesting that the recordings show how Beethoven or Mozart or Bach played their music. I am saying it is how pianists at the end of the nineteenth century played this music. And that includes most music, either older repertoire or then current works. For example, listen to Paderewski play Debussy. It is reported that Debussy went to hear Paderewski play and to his own surprise, was satisfied with the interpretation of Debussy's own composition (specifically, Reflets dans l'eau) given at that recital.

Listen — Debussy: Reflets dans l'eau (excerpt, played by Paderewski):

It is interesting that HIP performers and musicologists are very stern in their rejection of modern performance practice. HIP people are actually complaining against the generation of pianists who either rejected nineteenth century methods or were throwbacks. HIP performers are complaining about the wrong generation. I am proposing we go back and consider the ideas on the real nineteenth century performers, not the post World War I or even World War II generations.

Let me be very clear: Studying of these old recordings will increase the range of possibilities for consideration. Rather like this:

'Oh, They did that.'

'We could try this in the same place ...'

'Oh, that sounds well, doesn't it?'

Please follow the 'logic' of this.

These recordings can be a springboard to further investigations and above all an opening up of our thinking. Part of the reason this is necessary is that seventy-five years of education has convinced people that these sorts of devices are abhorrent. What is required is to listen to a great master and see that such devices are proper and justified tools of expressivity when used with artistic intention.

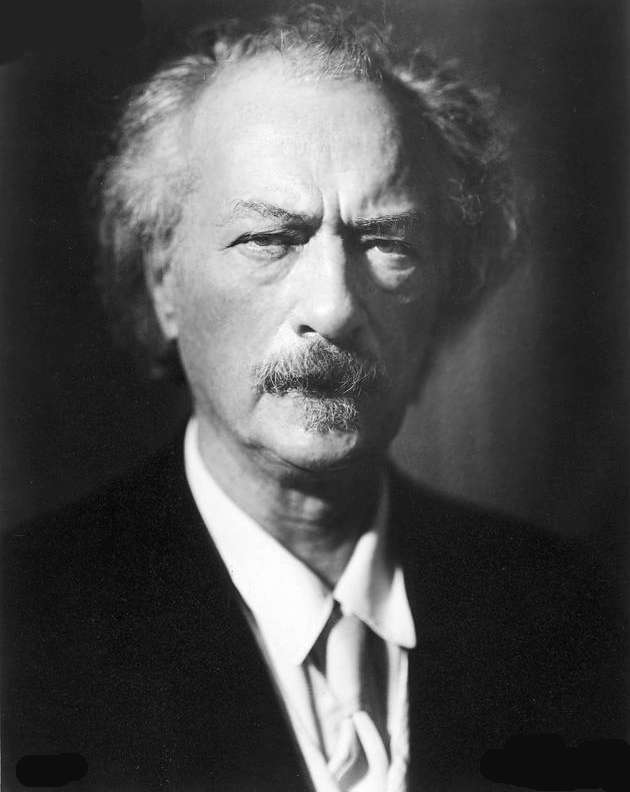

I suggest that modern harpsichordists would do very well to listen to the great pianist Ignace Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) for examples of how to roll chords, how to create rubato effects (both small scale and large), and how to 'recite' music. His methods are the most extreme of the recorded examples, with the exception of the much later Ervin Nyiregyházi - clearly and demonstrably influenced by Paderewski - and Glenn Gould too. (Most scholars seem not to have noticed this connection.)

Let me discuss each point in turn.

Rolled Chords

Probably nothing in the lexicon of nineteenth century piano performance practice annoys moderns listeners and pianists more than the rolling of chords, or as it has been dismissively (and violently called) the 'breaking of the hands'. What a crude term. Vicious and despicable.

Tobias Matthay referred to it as 'chord spreading'. A much better term. I will use it when I am speaking of the device as a legitimate musical method (which it is). If I am referring to a derogatory consideration of it I will call it 'the breaking of the hands'.

But even late romantic pianists who made recordings had a bad attitude towards the spreading of chords and even rolling of chords. Busoni dismissed the rolled chord sign at the end of one Bach work as 'effeminate'. Sadly, the marking is authentic (at least it appears so from the reprinted ancient manuscript which sits on the desk next to me). But, check Busoni's recordings for samples of the device!

From the use of this device we go directly to modern performances of the B flat minor Prelude of Book 1 of The Well Tempered Clavier where not a single chord is rolled, but each chord struck with simultaneity. I was going to say 'malignant simultaneity'. This is a work where rolled chords of some kind or other are clearly appropriate. But, it was and is rejected by almost all twentieth century harpsichordists.

Why did this happen? I suggest two reasons:

One, a simple change of fashion. One can no more 'explain' or 'deride' changes of musical fashion as one can 'explain' or 'deride' changes of sartorial fashion. This year short skirts are in, next year they are not. In this era men wore hats, nowadays they mostly don't. In 1905 pianists spread chords, in 1960 they did not.

Second, is the change of music making because of recording technology. Because modern musicians do not like to talk about fashion because it undermines the universalizability of their creations, they especially don't like to discuss how technology changes their methods of creation. The introduction of recording had enormous influences upon how music was performed.

Quite simply the 'breaking of the hands' does not sound well on record. That's the long and short of it. It reduces the percussive attack of the piano and it is the percussive attack that records better.

Aside: Notice that in the nineteenth century the piano was considered and usually called a 'singing instrument', while in the twentieth century is is classed as a 'percussion' instrument. This is a massive change in the perception of listening.

Going back in history then, where can we find an artist who spread chords as his norm and who is available on recording?

Wait for it:

Ignace Jan Paderewski.

Ignace Jan Paderewski (1860-1941), in circa 1935

No artist has suffered the insults, derision and ignorant attacks as much as this man who was once considered a 'Modern Immortal'.

All of these insults come from people who either:

A) are proponents of post-1945 Modernism,

B) were Paderewski's competitors, or

C) are woefully uninformed.

I give some credence to those who essentially said 'Paderewski represents the old style of performance that was wiped out by the Great War (1914-1919) and the change of thinking patterns that that entailed. We are in a new age, and hence we need a new style. Let us try something different - without insulting our grandparents for their taste in clothes or hats.' 'Who would wear their grandmother's hat?' is a legitimate question asked by Jacques Barzun somewhere in his voluminous writings on music.

What do we learn from Paderewski's recordings? He only recorded two works from the Baroque era on acoustic disc:

François Couperin: La Bandoline (Rondeau) and

François Couperin: Le Carillon de Cythère

Listen — Couperin: Le Carillon de Cythère (excerpt, played by Paderewski):

However, while these are crucial to our considerations, it would also be advisable to ponder his other recordings of say, Chopin.

Also, I must mention that pianists who perform Paderewski's own compositions without using his rubato and his spreading of the chords are doing a disservice to the ideals of Historical Performance Practice (especially when there are recordings of Paderewski performing his own compositions).

It is a sad fact that to my knowledge - and I would be happy to be proven wrong - Paderewski did not record any J S Bach, though he was praised for his interpretations of that Master.

What we learn from the recordings is this: Not all rolled chords are equal. Some chords are snapped, some a played slowly, some are spread wide, others are solid while the melody is adjusted (usually late, but sometimes early). Most of these rolls are not marked in the score by the composer.

Long ago, François Couperin permitted (and notated) rolled chords (even downward!) and Hans von Bülow advised that one way to determine how to roll chords between the hands was if parallel octaves resulted. (See his edition of the Etudes by J B Cramer.)

Why was this rolling or spreading done? Well, I suspect that pianists in those days had better ears than we, thanks to a century of pummelling noise as the background of our existence. For one thing (and to this I am indebted to the observation of R Murray Schafer) sound begins to become a musical pitch with 'onset transient distortion'. That is, the noise at the beginning of the pitched sound as the string or column of air gets up to vibrational speed.

This noise is omnipresent in the creation of sound.

Rolling of chords can do two things: accentuate this noise feature or reduce it. Indeed, that is what I said. If the roll is snapped then there will be more percussive distortions. If it is rolled slowly each subsequent note decreased the awareness of the distortion.

By the way: The indication of a rolled chord in early editions indicated 'Where it must be used' this did not mean that it could not or should not be used elsewhere a) at the player's discretion, or b) at places where it was traditionally used, like cadences. Besides, we forget that every marking added to the score increased the cost of the engraving and musicians because they are always poor are always frugal - publishers more so. (I suggest that rolled chord symbols might have been left out because they cost more, or added more costs to the publication and would have been omnipresent.) The absence of marking is not evidence of required omission.

Chords at the piano can then be solid or vaporous. Some chords can be harsh. Some can be silken. The pianist is free to make chords one or the other depending on the character of the music.

But one of the most crucial elements (mentioned above) of the nineteenth century is that they heard the piano as a singing instrument. In the twentieth century it is deemed a percussion instrument.

Why the change?

First, the ears of the nineteenth century piano listeners were directed elsewhere than the attack. Hammers were smaller and less hard (for the most part) than modern instruments. The dampers were smaller and cut off the sound less completely. But above all, listeners were attending to the meat of the sound, that is what came after the attack. They considered the piano a singing instrument.

But, further, the nineteenth century piano listeners were listening differently, specifically: they were following a dictum of elocution where what is important is the vowel sound, not so much the consonant. It is in the vowel that the Poet sings. Indeed, this is the chief feature of poets' recitation style. (One can find William Butler Yeats speaking an introduction and then reciting his own poem on the same recording. Notice the vast difference. It's how he 'sings' the vowels for the most part when he starts to recite. This has been commented upon by modern linguists with fearsome academic and Latin-esque articulation, though the linguists rarely discuss how the listener is hearing and why they are hearing a certain way.)

Next: one of the most important things to happen in the twentieth century performance method and reception was technological. In the twentieth century with the advent of recording and the decline of the piano as the crucial musical instrument, the sound started to shift in focus. The attack became what was best recorded. And please remember that recording artists were very quick to learn how to perform to the microphone. The best example of this is the crooner Bing Crosby. His career was the success it was because he understood how to sing to the microphone (and later other forms of technology too). Today the piano is a glorified xylophone. That is how we hear it and that is part of the reason we don't like the breaking of the hands: it falsified the accentual beat. In a word, it doesn't record well.

In the case of Paderewski the tone he creates (which receives the congratulations of even the most ardent of his opponents) is sublime precisely because he makes us attend to the meat of the sound: the ring after the attack.

And this shifting of attention brings out another aspect: the illusion of movement inside the sound after the attack. For we all 'know' that nothing can change the nature of a piano tone once it has been sounded.

Except all the rest that goes on and how the sounds interact with harmonics.

If those elements are adjusted well, then the inner life of the note begins. (For an example of the inner life notice that the G - second note - of Chopin's melody in the Nocturne in E flat Op 9 No 2 is sounding very strongly in the overtone of the bass note. If one delays the melody ever so slightly the sound is connected with that overtone and the resultant sound takes on a halo effect. Please listen to all of the great pianists born before say 1890 for the use of this delay in this oft-recorded piece.)

Tempo Rubato ('Stolen Time')

In one of his essays Paderewski writes that he does not have the moral force to return what he has stolen: what is stolen is gone.

A famed harpsichordist and organist from the mid twentieth century said emphatically 'NO RUBATO' in the performance of the Baroque. His was a reaction to the Paderewski generation.

Donald Francis Tovey was (in one of his letters) most offended that not two bars in Paderewski's performance of a Chopin Nocturne were in the same tempo.

But Tempo Rubato must be considered as a part of elocution.

We may delineate three types of rubato:

1) Non simultaneous events, mostly a delayed appearance of the melody. This method was actually described (and notated by Mozart, if you must know).

2) A malleable approach to the basic pulse which results in some beat being longer (mostly) and a few shorter.

3) Long term rhythmic organization or sense of span.

Paderewski uses all these methods, though not necessarily all in the same composition.

Elocution And Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the large scale science of convincing others. It was practiced by ancient lawyers, politicians and philosophers for the art of speaking and convincing in public.

Now rhetoric consists of several parts as defined by ancient texts. Most, but not all of the parts have been examined and evaluated in painstaking detail by modern scholars, including musicologists. However, I suggest that they have missed a crucial aspect for a very simple reason. The people who study and write these books are visually oriented and not acoustically oriented.

Therefore, they leave out a fundamental element of rhetoric, which morphed into nineteenth century Elocution: delivery. The actual speaking of the words. How they are pronounced, how they are joined together, how they are poeticized to make images in the listener's mind.

Elocution is that portion of rhetoric - the act of speaking and how the melody of the words is created. Generally, this part has been neglected in rhetorical studies which is often of merely visual/literary aspect.

It is the essence of how you breath, how you move, how your voice quivers. Actors know so much of this. What would you say to John Gielgud's comment on another actor and their difficulty in pronouncing a single phoneme? The ancients would certainly have concurred with Gielgud. This is part of pronunciation. (Hence all of the radical efforts with pebbles to cure some people of stutters mentioned in ancient texts.)

In music one of the highest goals (though so often forgotten) is creating the beauty of sound. This has slipped away from us as more of our sounds are pre-given.

But, it does not take long for the listener to notice some musicians have a specific and distinct 'sound' that is all their own. This is not just the instrument, and not just the recording. It is something inherent in the musician's equipment. I will not belabour this point because the modern ideation is so much opposed to it. Let it be.

At the harpsichord one must attend to the beginning and end of the sound (although a recent harpsichordist rejected my question about how to end the sound as unimportant). But, there is more, and here is where Paderewski's sense of responsibility is very high: he also attends to the middle of the sound.

How to create tone at the harpsichord? First, do not assume tone is just a given. Then remember these four things:

A) Timing is an issue of elocution;

B) Strike is a function of mechanism and body;

C) Release is the nature of motion. Mechanical release makes for mechanical playing;

D) Listen to the middle of the note, for that is where the swell of life occurs in the acoustic environment you inhabit. There is the life of the sound, not the mere clicking of bones.

An open minded listening to Paderewski's tone production, rubato and elocution will reveal all these points. Good luck. And remember Tobias Matthay's advice to musicians about to perform since it applies to listening as well: 'Enjoy the Music!'

Copyright © 15 May 2025

Endre Anaru,

Flowerdale, Alberta, Canada