SPONSORED: Think of Something Beautiful - Malcolm Miller pays tribute to contralto Sybil Michelow (1925-2013).

SPONSORED: Think of Something Beautiful - Malcolm Miller pays tribute to contralto Sybil Michelow (1925-2013).

All sponsored features >>

The Frankenstein Moment

JEFFREY NEIL describes an unforgettable evening with San Francisco Ballet

Liam Scarlett's Frankenstein is an inspiring production that demonstrates that at a time of dwindling budgets and an ever-bleaker universal aesthetic, we still have it in us to put on productions that churn the intellect, kindle the heart, and dazzle the senses. Co-created nearly a decade ago by The Royal Ballet and San Francisco Ballet, this adaptation of Mary Shelley's heady novel translates into visual spectacle and music many of Frankenstein's ideas, such as the danger of creating life without any clearly-defined ethical constraints. The ballet, performed in a regular spring series and a week of encore performances the following month, is a feat of artistic merit and intellectual inquiry that, frankly, would have seemed impossible had I not seen it with my own eyes.

Publicity for San Francisco Ballet's Frankenstein

Choreographer Scarlett, composer Lowell Liebermann, and designer John Macfarlane translate the pressing moral and philosophical questions that Mary Shelley wrote about in her 1818 novel. They did so, not by squeezing the story into a dystopian chic aesthetic, as has become the custom. Rather, the ballet's trio of collaborators celebrated the spirit of the Romantic era, and subtly interpreted it. The results were not derivative, but beautiful, and extremely relevant for the Frankenstein moment of human history that we find ourselves in - a time when the race to create Artificial General Intelligence is exposing our human frailty and limitless capacity for self-destruction.

Two centuries ago, Mary Shelley explored what might happen when a man's grief upset his moral equilibrium, and his instinct was to create life and unleash it upon the world. The ballet follows the basic plot points and themes of her novel. Victor's mother dies in childbirth, an event that shocks him out of his budding romance and engenders a festering melancholy in him. He leaves home to study natural philosophy, what we call 'science' today. At university, he becomes morbidly obsessed by the desire to bring the dead back to life. When he does succeed, he immediately repudiates his Creature - a perplexing reaction that the ballet explores. Victor's rejection of his creation brings out its latent human cruelty, and the Creature eventually kills everybody that matters to the young scientist, including his best friend and Elizabeth, his betrothed.

We have indeed reached 'The Frankenstein Moment' in the history of human civilization. In a recent New York Times interview Kaniel Kokotajlo, who served in the governance division of the world's preeminent artificial intelligence developer, OpenAI, warned that by 2027-28 AI will have replaced most jobs. AGI, which possesses superhuman intelligence, is believed to pose such a serious threat to humanity that an OpenAI cofounder, Ilya Sutskever, recommended a 'doomsday bunker' to protect the elite developers from an AI 'rapture'. In the past, OpenAI's board tried unsuccessfully to oust its CEO Sam Altman for failing to put ethical constraints on AI. Now back at the helm of the company, Altman was recently described rather flippantly by Business Insider as hedonistically enjoying the billions that have come from tying his radically-disruptive project to unfettered capitalism: 'In his free time, he races sports cars with his husband and preps for the apocalypse'.

This contemporary scientific recklessness may be what distinguishes the natural philosophers of Shelley's era from today's scientists. Before we see the curtain open on the first dancers, Macfarlane and projection designer Finn Ross translate the culture of natural philosophy - more or less, what we call 'science' today - into visual imagery. Through a combination of painting and digital projection, writing appears on a scrim and gradually the images of a spine and skull become discernible. Indeed, in the late eighteenth century, the various disciplines of natural philosophy - eg, the study of chemistry, anatomy, and biology - were tied to the book - be it the diary where contemplation and philosophical reflection took place, the log for experiments, or the journal for writing papers to share with a community of peers and benefactors. It also was not uncommon for a scientist from that era to write poetic verses. What we have, then, is a culture in which innovators of the physical world were no less tied to moral, existential, and even spiritual concerns. Macfarlane makes that statement boldly by demonstrating how our view of the human body is constituted through the process of writing itself and all that writing embodies.

There are a number of philosophical and literary texts that form the backbone of Shelley's Frankenstein: Milton's Paradise Lost, for example, which travels through heaven, hell, and Earth to understand why evil is so intertwined with life; but this production visually and musically captures the spirit of the Romantic era itself, with its emphasis on becoming a channel for a life force that connects human emotion to other animals, plants, and even to inanimate forces like burning flames, chill air and photosynthesis. Thus Macfarlane's first scrim gives way to another that beautifully depicts tormented weather-generator of electrical charges and shifting air masses, which affect the emotional temperature and psychic barometric pressure of even the genteel society in the drawing rooms with which the ballet opens.

Lowell Liebermann's score, conducted by Martin West, feels like a synthesis of Romantic music and then some, with a prologue in Vienna that was vaguely reminiscent of the first chords of Tristan und Isolde - a brooding melancholy with a percussive punctuation. San Francisco Ballet Orchestra exuberantly plays this score that also has echoes of Grieg, Wagner and Dvořák - brassy public fanfare and the intimate longing of winds and strings. I am reminded, too, of Aaron Copland, romping between the Romantic era that generated Frankenstein and a more modern sound.

Lowell Liebermann.

Photo © 2015 Joseph Moran

Scarlett channels the Romantic focus on the various phases of the life force and its connection to human creation. This can be subtle, as in the drawing room of Act I, where a static elderly couple stands behind the frolicking Victor and Elizabeth, performed by SF Ballet-trained Max Cauthorn and the Spanish ballerina Dores André. Amid the plaintive strings of the orchestra, the young couple's youthful ebullience contrasts with the more rigid and quiet movements of the elders. The drawing room revelers make playful butterfly wings with their arms, heads bobbing to the music's long, sustained notes. All that innocent effervescence is manifest in the shimmering vessels of maidens in their Georgian gowns and prancing lads in tight silken breeches.

A scene from San Francisco Ballet's Frankenstein

The pregnant Caroline Beaufort, Victor's mother, played by Elizabeth Mateer, bustles and fusses in an unforgettable gown of many beaded and embroidered textures, whale blues and silvers. There is something of the mystery of life in the graceful pas de deux that rock the stage juxtaposed against the tipping and swooping of the expectant mother, until celebration itself seems to morph seamlessly into mourning and death. Although there is a separate cemetery scene after, Scene I does away with the artificial delineation between life and death, manifesting the Romantic spirit that feels the life force even in the throes of dying. We experience in this first scene the very essence of Romanticism.

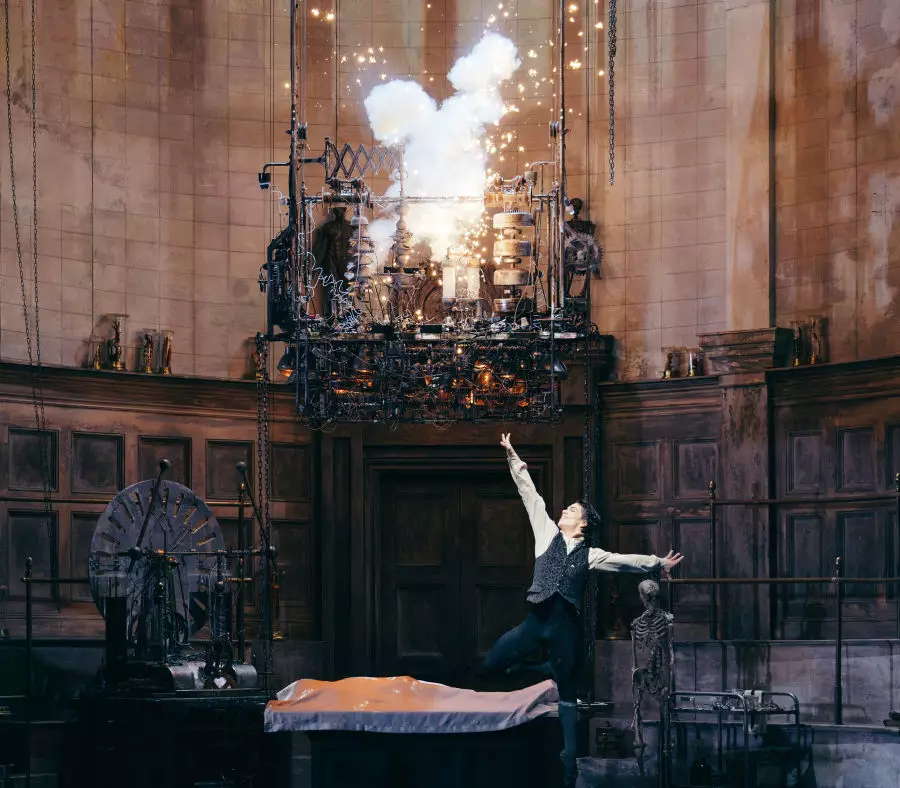

The Anatomy Theatre at Ingolstadt University, a spectacular set of wood-paneling with a gray wash, is the backdrop for Victor's transformation. The men are dressed in a harmony of metallic colors, except for Victor himself in a red coat. An anatomy lesson is transformed into a delightful dance among the scholars with their books, shrugging at cheeky, leaping nurses. The orchestra creates music that is grand and frantic, but also playful and swirling. The following scene occurs in a tavern with barmaids in red and gold, smoldering embers of eroticism that gather up in the musical loins of Victor himself, spilling out into the creation scene. Max Cauthorn's subsequent solo in the anatomy theatre is a dance of longing for inspiration, a bearing of the soul's desire to create - all Romantic themes conveyed through plentiful use of strings and winds against sounds of brass and percussion that mimic churning cogs and electrical sparks. Victor is hopeful, then reluctant, to unveil the corpse, and finally ecstatic during the pyrotechnic show of raw electricity coming through an open dome. At the end of the scene, he is overcome and mounts the cadaver. Cauthorn channels all these life forces - electricity, movement and erotic energy - showing that delight and longing that comes from creating.

A scene from San Francisco Ballet's Frankenstein

Frankenstein's rejection of his creature is perplexing - an enigma at the heart of the story. However, it may never have made as much sense as now. The drive to create autonomous intelligent life, coupled with hitherto-unknown levels of fame, power and money in its would-be creators - has prepared the ground for such a confrontation. In the ballet, the raw power and danger of the life drive versus the genteel trappings of civilization come out, for example, in the contrast between the bare-branched stylized trees on one side of the set and the neoclassical building on the other at the opening of Act II. When young William Frankenstein dances with the Creature, the child teaches him the vocabulary and the phrases of civilization through his movements. There are playful pirouettes and leaps, the great raw beast doing a pas de deux with the blindfolded boy. Corps dancer Nathaneal Remez premiered the part of the Creature on 27 April 2025 that much more senior Wei Wang danced in the initial March run of Frankenstein. Remez beautifully rendered the loose, skipping strides of this uninhibited force of life, as the Creature joyfully chases, then partners with, then squeezes to death William, played delightfully by teen dancer Oliver Gurrea.

As Victor Frankenstein attempts to return to the normalcy of his pre-creation, 'civilized' life, we are treated to interior scenes of waltzing duets, the Creature slinking in and camouflaging himself among the others, showing how perfectly he has learned to mimic the ways of the society from which he is excluded. There is a sense of mounting danger, conveyed by the celesta, the timpani and the intrusion of discordant chords. In her dance and death with the Creature, Dores André's talents become increasingly apparent through sautés and grand jetés. The Creature's danse macabre against a backdrop that seems to portray the Pillars of Creation - stars, smoke, light - shows the inexorable, amoral power of the universe. We see both the human desire for life, light, and connection and the irrepressible, ineluctable return to darkness and death that awaits humanity at the hands of its Creature. It is all terrifying and, strangely, sublimely beautiful.

A scene from San Francisco Ballet's Frankenstein

Macfarlane's production brought the performance out into the public spaces of the War Memorial Opera House: there were Edison light bulbs in the permanent chandeliers, nineteenth-century gadgets with dials and coils displayed on tables and pedestals, and black and lavender touched throughout. We walked the halls of round banquette settees and set our drinks on high tables with candelabras and black candles, savoring an unforgettable evening that blended visual splendor, masterful dancing, and very moving Romantic-inspired music.

Copyright © 4 June 2025

Jeffrey Neil,

California, USA