DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Music and the Visual World, including contributions from Celia Craig, Halida Dinova and Yekaterina Lebedeva.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Music and the Visual World, including contributions from Celia Craig, Halida Dinova and Yekaterina Lebedeva.

A FAST PACE

FRANCES FORBES-CARBINES explains why reading Eleanor Chan's new book 'Duet: An Artful History of Music' is similar to having an animated conversation with a particularly sparky, clever and knowledgeable friend

The 'prelude', rather than prologue, of Duet: An Artful History of Music by classically trained musician and art historian Eleanor Chan opens with the author giving a public performance at Brighton Pavillion in the UK. It is her first professional concert, and she is all of seven years old. A life in music is to follow, both in terms of career and of lifelong passion and fascination.

Chan writes:

To be a musician is to walk this tightrope and continually negotiate the balance between the visibility of what we hear, and the acoustics of what we see.

The book explores choral music, the music of early hominids, the first sheet music notation and scales, Taylor Swift's copyright battles and the musicality of Beyonce. The thread running throughout, Chan states, is one of capturing for the reader 'the briefest impression of just how much visual information goes into the experience of music-making'.

Chan takes us right back to eighteen thousand years before the birth of Christ, to the time when in the entrance of a painted cave at Marsoulas, France, a conch shell was fashioned into a horn in order to make music. Music archaeologists, the author states, have conducted performance experiments to work out how these rudimentary instruments might have sounded. In the case of the conch shell:

this meant playing a 3D-printed resin replica of the instrument on the edge of the ravine outside the opening of the cave [...] Observers of the experiment noticed that the sound of the seashell 'filled the cave', but without any of the eerie reverberations and phantom 'warblings' or 'throbbings' of tone recorded at other cave sites.

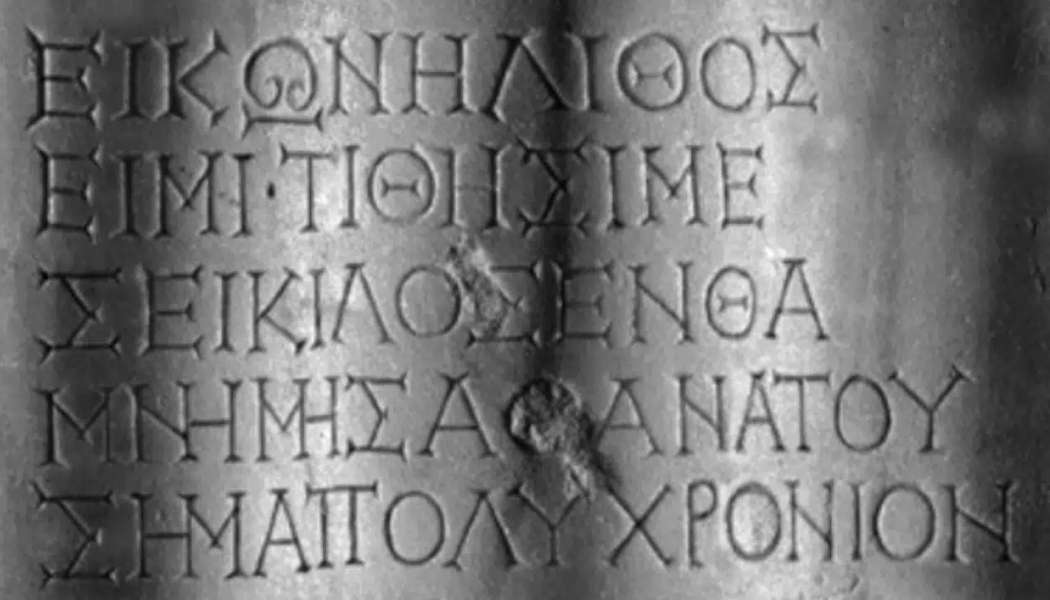

A moving passage in the book is when Chan turns her attention to the Seikilos epitaph, 'the oldest complete song in the world'. Looted in 1883 from the ruins of the ancient Greco-Roman city of Tralles, in the hills above the modern city of Aydin in south-west Turkey, it 'commemorates in music someone lost and loved'. Dating from the first or second century AD, the epitaph is chiseled upon a standing column, reading:

I, the stone, am an image.

Seikilos placed me here as a long-lasting sign of deathless remembrance.

While you live, shine

Have no grief at all.

Life exists only for a short while

And Time demands his due.

The Seikilos Epitaph. Photo: Lennart Larsen

Chan explains:

The song remembers the life of a woman named Euterpe, perhaps [Seikilos'] wife, lover, sister or daughter [...] But this also could have been a lament by Seikilos for his own mortality.

The musical elements are above the words themselves, swoops and dots that represent ways that the words should be manipulated into song. In 2018, the author continues, in Antigone Journal the classicist and Oxford professor Armand D'Angour:

suggested that the lyrics were inseparable from the way that the song had been composed, melodically - an argument that would have been unthinkable only ten years before.

An interesting couple of pages look at the photographer Man Ray's work Le Violon d'Ingres, the famous and much-reproduced surreal image of a model's bare back with what appear to be violin F-holes below the curves of her waist, rendering her form as though she is a living violin instrument.

Man Ray's Le Violon d'Ingres

The model, Prin, Man Ray's lover whose alias was Kiki de Montparnasse, is shown without arms and with much of her face obscured from the viewer. In terms of feminist readings, as an artwork it's 'pretty problematic', Chan writes, but still she quietly always has loved it. Why?

Man Ray transforms Prin into the holder of a deep musical harmony [...] she thrums with resonance.

Violon d'Ingres is a French idiom, explains Chan, meaning 'private passion', hobby or even side-hustle. Chan expounds:

Both phrase and image are emblematic of the way that music, although so often relegated to a supporting role - 'my other hobby' - has been crucial to the way that artists see the world. Throughout history, the theme of music has enabled human beings to refine their ways of seeing, and to challenge the limits of their vision.

Duet certainly races through historical epochs and geographical places: one moment we are exploring Diaghilev's approach to the marriage of music and art with the Ballets Russes in 1910s Tsarist Russia; the next we are transported to the Rhine in the twelfth century to consider the aura, visions and notations of medieval mystic Hildegard von Bingen, writing music that could recapture the original joy and beauty of paradise.

Eleanor Chan

The fast pace is not, however, to the book's detriment: far from it - the effect is akin to having an animated conversation with a particularly sparky, clever and knowledgeable friend. Having read the book I say to you wholeheartedly: befriend Duet. Your life will be the richer for it, dear music fan.

Copyright © 31 May 2025

Frances Forbes-Carbines,

London UK