- Phill Niblock

- Igor Markevich

- Francis Thorne

- Dan Rowe

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Amy Marcy Cheney

- Tyzen Hsiao

- Orchestre Nouvelle Génération

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

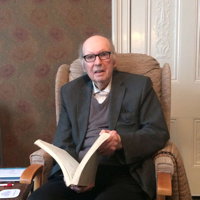

SPONSORED: Profile. A Gold Mine - Roderic Dunnett visits Birmingham to talk to John Joubert.

SPONSORED: Profile. A Gold Mine - Roderic Dunnett visits Birmingham to talk to John Joubert.

All sponsored features >>

A DIFFERENT KIND OF MINIMALISM

A P VIRAG investigates Ervin Nyiregyházi's

'36 Selected Works for Solo Piano'

I have sounded the depths of horror - only to be made aware of still lower depths. - H P Lovecraft: 'The Diary of Alonzo Typer'

Towards the end of his life the great composer Franz Liszt was writing a book on harmony - for the future. The book is sadly lost, but Liszt's late works exist and are a very clear indicator of his ideas and intentions.

Liszt's late compositions have often been considered in relation to the music of Béla Bartók, and I detect a relationship between Liszt's last symphonic poem (From the Cradle to the Grave) and certain works of Arvo Pärt. Liszt did indeed throw his lance far into the future.

But, really, composers have not been lining up to take up Liszt suggestions, except in a few such cases.

The single most important exception is Ervin Nyiregyházi (1903-1987), who, thanks to his supreme dedication to the memory of Franz Liszt, is by far the most devoted to those ideals.

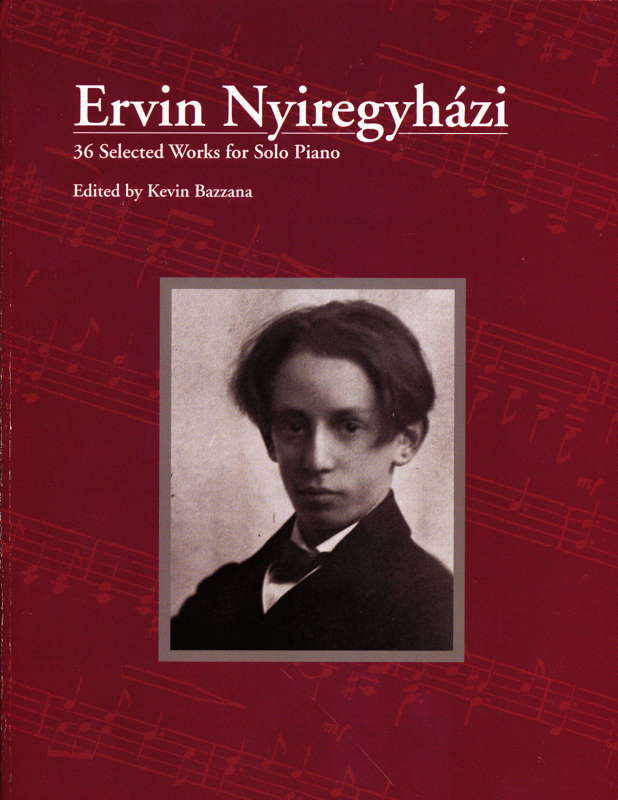

Ervin Nyiregyházi: 36 Selected Works for Solo Piano,

edited by Kevin Bazzana, published by Carl Fischer (2019)

Kevin Bazzana writes in the preface to this edition:

The overriding influence on Nyiregyházi's music was the idiosyncratic, experimental late style of Liszt.

Further, Ervin Nyiregyházi has very clearly understood Liszt's ideas, absorbed them and transmuted them through his own personality. This is not mere impersonation.

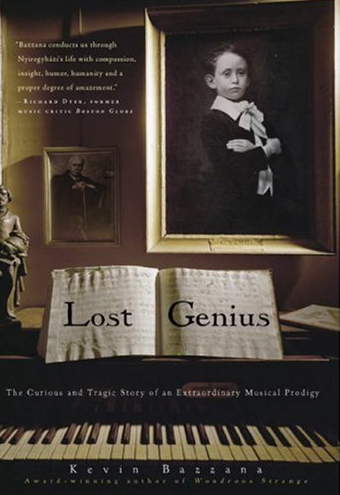

For those interested in Nyiregyházi's personality and life story, I highly recommend the book by Kevin Bazzana: Lost Genius: The Curious and Tragic Story of an Extraordinary Musical Prodigy (2007). However, so much is dismal, depraved and unpleasant in the biography that I also recommend taking a shower after each bout of reading. Nyiregyházi's life was more sewer-water-drenched than even that of Charles Bukowski.

Kevin Bazzana: Lost Genius: The Curious and

Tragic Story

of an Extraordinary Musical Prodigy.

© 2007 Carroll & Graf

Nyiregyházi began life as an amazing child prodigy. A book entitled, in translation, The Psychology of a Musical Prodigy by G Révész - according to the information I have: German edition: 1916, English edition: 1925, see: archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.218386 - was even written about him at the time. He performed with great success, and then vanished into career stagnation, financial indigence, cultural extinction, blind anonymity, moral self destruction and a Bowery level street life. In the 1970s, after decades of degrading obscurity, he was heard performing and subsequently a few recordings and performances resulted in a strange after-twilight glow. People have been trying to understand him, his piano playing and his life for a long time. But his compositions have remained out of reach, since only a handful were ever published.

Thus, while a significant number - perhaps all - of Nyiregyházi's piano performance recordings have been released, we have had to wait until 2019 for a collection of his compositions (which number in the hundreds) to be published. Here, thanks to Kevin Bazzana, we have a sampling of works to begin consideration.

The volume includes a biography, numerous photographs, and musical commentary. Bazzana is thoroughly conversant with Nyiregyházi's life and has close ties with those who knew him. He writes well, though occasionally with an insouciance that is the voice of a scholar trying to be hip.

While the edition itself is very fine - that is, edited well - the engraved score is only somewhat satisfactory, because the engraving is not in the classical music manner, but evidently pop music-style in layout and appearance.

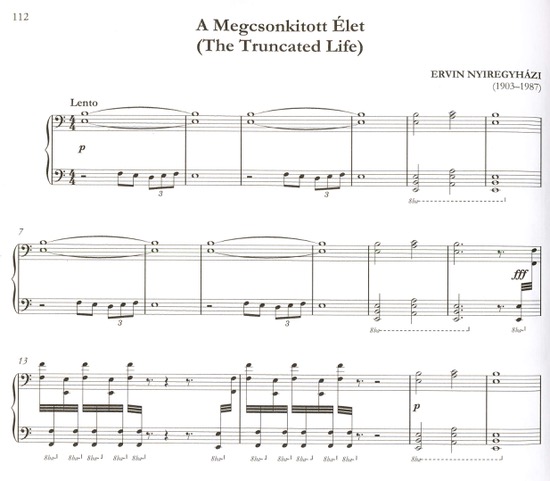

A sample page from 36 Selected Works for Solo Piano

In many of the works, there is too much white space, and the staves for the piano are too far apart. Page turns are not well planned and the musical notation is hard to read. As for the binding: I do wonder if any publisher ever tries to place these books on a piano's music rack to see what happens. (Hint: the pages either do not lay flat, or the book refuses to stay open unless the binding is broken or bent by hand.)

There are different types of compositions in Nyiregyházi's oeuvre:

- Early works

- Massive, epic compositions

- Miniatures (mostly late works)

Early Works

Of the early works, it seems hardly necessary to speak. They show promise, though none of the transcendental and precocious genius that caused Nyiregyházi to be hyped so much, both in his own life and later. No insult is intended. There are many children who create considerable works which if judged by adult standards are not actually that impressive.

Nyiregyházi's early compositions are trite, simple, amateurish and in some cases are of the lowest salon music manner. Still, there is something suggestive there of the sound world that Nyiregyházi inhabited.

The Massive Works

These are of an entirely different category and show Nyiregyházi at his most maniacal and thunderous. From the point of view of music theory or music history, one would be hard pressed to praise or justify these pieces. They are harmonically old fashioned (diminished seventh chords!!!???), structurally simplistic, melodically either banal, or reminiscent of an earlier composer - one melody in one work not published here reminds me of 'Somewhere Over the Rainbow'.

However, there are also two interesting aspects that make up for all. First, Nyiregyházi frequently combines a series of chords in a very unusual and suggestive fashion.

Further, and again following Liszt, many of the works are based upon a single germ motive that finds its way into the melody, the harmony, the accompaniment and the aspiration. This is decidedly a Romantic era notion and assists the works achieve a Goethe-ian level of integration - something that does not always occur with twentieth century compositions, which often stray too far from the opening sounds.

The major works are also sophisticated in one specific way: the gigantic and volcanic pianism that Nyiregyházi represented. They can include detailed instructions on rubato (drawn from notation in Liszt's works) and require the most ardent forcefulness of piano playing, the most gigantic sound, and above all, the most overwhelming spirit, supreme vehemence and coruscating vitality.

For this reason I ask - no, demand! - that 99% of all pianists should not play them. You do not have the soul or life experience for it.

And this is a great danger in this publication - one of two, see below - that Nyiregyházi's mad, monstrous and cosmic vision will be sanitized, reduced, emasculated, decontaminated, and trivialized by teachers and pundits who have no soul, have never suffered, and are utterly lacking in musical and pianistic daring, not to speak of mystical endeavour.

I shudder to see the day when one of Nyiregyházi's works is played at a piano jury in some obscure provincial town's conservatory or university. Or that the smaller works will be given to a child pianist to play for parents and relatives at a family gathering.

Please do not let this happen.

The reason is simple: Nyiregyházi suffered so much, saw into the most horrifying depths of human life in its squalor and futility that a piano jury is the last place such a kind of music should be exhibited. A family gathering is not the place for this.

But, it will happen - just as Beethoven's works have been sanitized and emasculated. Beethoven's music - which should rock the foundations of a corrupt universe - is instead the subject of witless banter about who best played the trills in Op 111. We can't save Beethoven - he is too far gone now - but this trivialization must not happen to Nyiregyházi.

The issue of performance practice with Nyiregyházi's music is sadly not clearly understood. The methods he used - nonsimulatneous hands, octave doublings, giant sonority, etc - are so far from how people imagine the piano is supposed to be played that Nyiregyházi's playing is considered insane - or incompetent. It is neither. Two performers who have grasped Nyiregyházi's style and performance manner are Michael Sayers, and one pianist, who, like Nyiregyházi and Sorabji, prefers anonymity.

Miniatures

The third group of Nyiregyházi's music - and perhaps the most important - are those works that I suggested be considered a ‘different kind of minimalism'. Not the kind that takes three notes and repeats them for several hours, but the kind that is simple because every excess has been expunged, every gesture, every idea has been reduced, distilled and reduced again (like some wild and ardent homeopathic elixir) until hardly anything remains, except the most searing cosmic emotion.

In these tiny works, seldom more than a page long, Nyiregyházi followed the ideation of Franz Liszt as mentioned. Motivated by his own life's events, media events (ie the assassination of JFK), and much deep literature, Nyiregyházi created tiny masterpieces.

There are frequent allusions to the Hungarian scale - C-D-Eb-F#-G-Ab-B-C, which is not really much Hungarian, but leave that aside - but more often, just the most simple fragments of ideas cast in the simplest of form. And in those few notes lie realms hidden and eternal.

There are masterpieces here waiting to be discovered. Indeed, there are many more. Nyiregyházi was very prolific and perhaps hundreds of works await the light of day.

However, as mentioned above, there is also a very great danger:

The worst thing would be to allow young students to play this music because it is physically/technically easy. It is dangerous, diseased and insane music. As much give a text of the Marquis de Sade to a child because the French language writing is good.

So, my with my strongest warning: Do not give this music to children!

Now, having said that the music is dangerous, diseased and insane, I must point out that so is our world. Nyiregyházi experienced life in its most dank, dismal and vile forms. He, who had walked with the gods, was reduced to consorting with apes, subhumans, zombies and ghouls at the lowest edge of society. (I wonder if he knew Bukowski - they might have raised many glasses well together.)

But, Nyiregyházi continued to create, to mirror the horror, and continued to fight against this madness in spite of all - without allies and without help, except alcohol, prostitutes, and many, many wives.

Ervin Nyiregyházi at the piano

Ervin Nyiregyházi gazed into the abyss and came back to tell us of it. Not the abyss of Lovecraft - which is child's play in comparison. No, the abyss that yawns in a gulf that even the Gnostics dared not mention.

Do not take up this music because it is easy. Take it up because it is difficult: hard beyond all adamantine steel.

Nyíregyháza, Hungary