WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

VIDEO PODCAST: Women Composers - Our special hour-long illustrated feature on women composers includes contributions from Diana Ambache, Gail Wein, Hilary Tann, Natalie Artemas-Polak and Victoria Bond.

VIDEO PODCAST: Women Composers - Our special hour-long illustrated feature on women composers includes contributions from Diana Ambache, Gail Wein, Hilary Tann, Natalie Artemas-Polak and Victoria Bond.

- Michael Tremberth

- Parlophone Records

- Antoine Busnois

- Leipzig Opera

- Kangasala

- Langgaard: Sensommer

- Jupiter Quartet

- Emmy Lindström

THE BALLETS RUSSES

GEORGE COLERICK tells the story of the

early twentieth century ballet company

By 1903, Isadora Duncan was famous in the west for her revolutionary if idiosyncratic approach to dance, and in locations remote from the ballet stage. The young Russian choreographer Michael Fokine could not follow her total disregard for tradition, but admired her naturalistic approach, such as refusing to dance on pointe. In the St Petersburg ballet, his creations were moving away from rigidities of classical style, but there was strong opposition to some of his changes in court circles. This was the capital where French fashions had dominated among the rich. Over six decades Russia's internationally famous nineteenth century choreographer had been the Frenchman Marius Petipa, through to Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty (1890) and Glazunov's Raymonda (1898). Fokine was to be his successor and assembled the most famous-to-be dance team there, including Pavlova, Karsavina and Nijinsky; all four would eventually migrate to Paris.

He became interested in a circle which grew around two men who had met as undergraduates and were editing a forward-looking magazine The World of Art: Serge Diaghilev and Alexander Benois, painter and future scene designer. Diaghilev was multi-talented, but gave up his ambitions to be a composer when Rimsky-Korsakoff told him he lacked talent. He was first taken on as an administrator by the Imperial Theatre; but would not compromise on a new approach to Delibes' ballet Sylvia, and was sacked. His destiny was to become a world-famous impresario, aristocratic in manner but able to pick the best collaborators.

A 1911 photograph taken by Nicolas Besobrasov at Beausoleil (Monte Carlo) of a group of supporters and members of the Ballets Russes in 1911. In front, Alexandra Vassilieva, and behind, from left to right: Botkine(?), Pavel Koribut-Kubitovitch, Tamara Karsavina, Vaslav Nijinsky, Igor Stravinsky. Alexandre Benois, Sergei Diaghilev and K Harris

Fokine was being obstructed, so his chance came when Diaghilev took a company in 1907, firstly for opera, on tour to Paris. He joined it to create by 1909 the ballet on Chopin's music now known as Les Sylphides, but Diaghilev sensed that the audience were ready for greater innovation. The Polovtsian Dances from the opera Prince Igor were given astounding choreography to music of a kind of previously unknown, so vital and exotic. Cleopatra did not use the familiar personalised history, but was first in a plan to display the beauties of all great civilisations, an early kind of multi-culturalism. Its theme was based on an 'Asian' notion that a man would willingly suffer death for one night of voluptuous pleasure. Its ballet was a compilation from several Russian composers. Then came the aural and visual delights of Scheherazade based on tales from the Arabian nights. In that time, before cinema had introduced sound, Rimsky-Korsakov's sensuous confection seemed to illustrate the unknown, the ultimate Oriental fantasy.

A Russian court painter, Leon Bakst's decor was able to evoke parallel responses, conceptions which are no less astonishing even in today's jaded post-modernist phase. He made original use of veils and harem pantaloons in place of the tutu, and his two works, Scheherazade and Cleopatra, had Parisians shopping for exotic home decorations. The original episodes of Scheherazade were not related to sex, but Fokine's version was carnal and violent. Rimsky-Korsakov, recently deceased, might have objected to this interpretation in a different medium, and his widow did so in vain. Two other new ballets on music from the earlier nineteenth century succeeded without controversy: Carnaval by Schumann and The Spectre of the Rose with a score which Weber had once used to make the waltz 'respectable'.

Poster depicting Nijinsky in

The Spectre of the Rose

for the 1911 Ballet Russe season

The visual and theatrical talent of the team Diaghilev had assembled brought ballet into a new century. Theme and music would be conceived together, incidentally avoiding such problems as that over Scheherazade. Diaghilev then took a risk of historic importance, commissioning the unknown twenty-eight-year-old Igor Stravinsky to compose music for a gorgeous, enchanting legend, The Firebird (1910). This was once more ideal for Bakst's decor, sensationally matched by Stravinsky's use of instruments in a luscious score. It was inspired by the skills of his teacher, Rimsky-Korsakov, but his next step was in search of a new style, divergent, more austere and nearer to that of Mussorgsky.

Stravinsky improvised on the germ of story, a concertante fragment between piano and trumpets. It would then be expanded and laced with several of Russia's popular and folk melodies. The piano part represented a puppet facing a hostile world, to be interpreted inimitably by the young Nijinsky. With Fokine collaborating, and Benois as designer, a pathetic story of jealousy emerged within a fairground scene, Petrouchka. Startlingly original, like a Harlequinade gone wrong, it was a triumph of combined talents.

Vaslav Nijinsky as Petrouchka in 1910 or 1911

Diaghilev produced these two works by 1911 to great acclaim, and they initiated a move away from literary themes. Many ballets would in future have music composed to order; two years later, a third such work resulted in one of the most infamous riots ever by a supposedly civilized musical audience. It made Stravinsky the most notorious of young composers, one of the fastest promotions in musical history.

This was The Rite of Spring, depicting the selection, rape and killing of a virgin, an ancient Russian ritual to the earth god of fertility. The musical score affected the sensibility of many, and even the dancers found it very difficult to count the rhythm. The extremities of the choreography shocked probably no fewer; the dancers had to adopt animal-like postures, grotesque even more so by comparison with the elegant upright stance of tradition. It was a lurch into primitivism, crashing harmonies, violently repetitive notes and rhythms. 1913 was a time when certain 'advanced' composers seemed to be taking leave of traditional melody, and some listeners were confused. In fact the melodies are broken but intense and thoroughly memorable. Visually and in emotive force, the work was reaching the ideal of an integrated work of art: music, scenario, choreography, decor.

An opera-ballet to The Golden Cockerel resolved a problem in the original work. The dance sequences the composer had insisted upon were too difficult for most lead singers, so the innovation was to have double casts, a practical device used later in Stravinsky's Renard and elsewhere. Diaghilev then found music with a restrained, perhaps more authentic Oriental touch. This was by the Russian Balakirev to become the ballet Thamar.

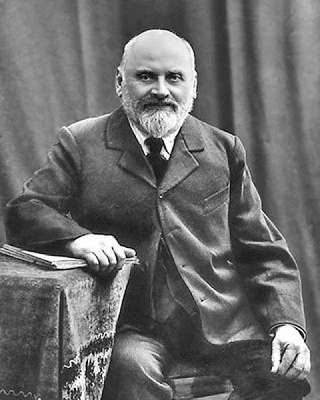

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev (1837-1919) in about 1900

In between these works, Diaghilev turned to two contemporary French composers with a marked difference of approach to rhythm. Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe (1912) to a Classic Greek scenario was an orchestral tour de force, inspired flute passages contrasting pagan vigour with sensuous, elongated melodies. This was thought difficult, but Ravel's impression of a grand ballroom's mystique, La Valse, was more surprisingly rejected by Diaghilev. One likely explanation could follow from conductor Michael Tilson Thomas' experience:

It requires such constant attention to balance, to nuance, to articulation and to continual changes of tempi. Orchestras have described the experience of doing La Valse with me as accelerating around a racecourse without flinching in the turns.

In total contrast, Debussy's Jeux, describing a search for a tennis ball, has elusive and broken rhythms. His Apr`s-midi d'un faune, with its leisurely pace and chords suspended in mid-air, was widely thought not to be danceable. Nijinsky found a unique approach, dancing 'above' the music, finding a sensuality which helped to turn his performance into part of a controversial legend. The Bolshevik revolution of 1917 brought many Russian emigres to France, and Leon Bakst decided to stay. Sergei Prokofiev, spending a lengthy 'holiday' from Russia, would compose spiky, modernistic scores over more than a decade. He started with the Scythian Suite which was barbaric in ways which suggested Stravinsky's influence. Diaghilev's late choices included three more of his works: The Buffoon, The Steel Pace (1927) on a modern factory theme, and finally The Prodigal Son, more lyrical, and used as material for his Fourth Symphony (1930).

Diaghilev had never intended his creation to become a museum for 'White Russian' culture. Biblical themes were not without spice, and Florent-Schmitt could provide some in his Tragedy of Salomé. So Richard Strauss was given a divergent story, Jacob's Ladder: he later confessed that its religious theme had been beyond his sympathies.

Diaghilev reacted to changing conditions by linking with contemporary artistic fashions, such as Surrealism which encouraged incongruous relations between the music and the theme. He requested from the idiosyncratic Eric Satie Parade, with a light, jazzy score including a typewriter and later Jack in the Box, both on amusingly commonplace themes. They were admired by the younger Poulenc because, as he said, they were close to the spirit of Paris, as Petrouchka had been to old St Petersburg. He and others wanted the new music to be clear, healthy, robust and French. That could describe another success, La Boutique fantasque (1918), except that it was Italian, an even more exuberant romp which was a collage of Rossini themes. A historic nationalist score by Manuel de Falla featured Spanish dancing and flamenco in The Three-cornered Hat.

Picasso's costume design for

The Three-cornered Hat (1919-20)

The contemporaneous group of French composers,'the Six', responded favourably to the stimulus of the Ballets Russes. Darius Milhaud had put an extended stay in Brazil to best use, composing ballets such as Salade with its modern dance rhythms, and a French strain with his Blue Train, musically recalling the naughty nineties and popular theatre. A long-term success had been Les biches (1924), flirtations with emancipated young ladies, teasing 'flappers' in short skirts, dancing to rhythms which range backwards two centuries from the 1920s. Its composer Francis Poulenc could span the ages even within a single movement, here creating one of the wittiest of all ballet scores.

In those excursions into magic, fairgrounds and pre-history, Stravinsky had astounded Western audiences exploiting the exceptional freedom in Russian rhythms; but some thought his Soldier's Tale (1918) was rhythm without feeling. His 'primitive' phase was unlikely to continue after 1914 when Europe's armies would practise barbarism on another stage. He settled for much lighter themes such as Renard, a foxy tail, playing to his other strengths such as parody. Using small instrumental ensembles was a useful option, especially as Diaghilev had lost a fortune with London productions.

Stravinsky had greater success looking elsewhere for melodies and composing music for more traditional ballets such as in The Fairy's Kiss. This used at least eight of Tchaikovsky's lesser-known songs. Stravinsky exploited their potential to differing emotive effects, dreamlike or ironic as suited a disquieting story from Hans Andersen. He transformed them with some of his own bridge material into the genial central movements of his longest ballet about a man tricked into a false and disastrous betrothal. Its first section contains the disquieting Lullaby in the Storm and the enigmatic finale with its unsettling harmonies is built around Tchaikovsky's best-known song, None but the weary Heart.

Neo-classicism was rearranging music from earlier centuries, a the fashion of the early 1920s when art music was uncertain which new direction to go. It was well adapted to the useful style of Pergolesi's music in the comic ballet, Pulcinella, for which Stravinsky added piquant instrumentation. An entirely new direction was Les Noces (The Wedding), an ancient Russian ritual but influenced by African rhythms, with a new combination for ballet using chorus, four pianos and percussion. This music alongside those first three of his ballets show exceptional variations in style far beyond what could be expected in four works by any front-rank composer. He provided no more fireworks, but lastly a delicate essay in neo-classical style, Apollo (1928). These final contributions were relaxing and nearer to cool, abstract art.

As the shortest policy directive Diaghilev had said Astonish me! Yet the law of diminishing returns seems to govern human creativity. These new works of the 1920s could not generally match the originality and significance of the earlier ones.

Serge Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes

Diaghilev remained the integrating force of the Company until his death in 1929. Stravinsky was distressed far beyond his concern that he might as a result lose his musical direction; he needed to go on his travels to find his creative purpose once more. Diaghilev's ballet troupe was terminated, though the name was taken up by others; one of his team, the choreographer Balanchine, successfully set up long-term in the USA. Ninette de Valois started as one of his ballerinas, then became a leading force in Britain without whose work and persistence, it is said, the Royal Ballet would not have been born.

Constant Lambert had composed for the Ballets Russes a Romeo and Juliet, and in his distinguished book Music Ho! he wrote:

In his palmy days before the War, Diaghilev was a space-traveller, bringing to the Western world a picturesque oriental caravan laden with rich tapestries ... appealing to a more intelligent audience than that sought by the ordinary commercial impresario, who would be forced into a policy of novelty and sensationalism that gathered speed as it went.

The 1912 oil and cardboard painting Ballet Russes

by German painter August Macke (1887-1914)

In music his genuine taste was for the luscious, in decor for the opulent. In spite of all his convincing toying with post-war intellectuality, his favourite ballet was probably Scheherazade.

London UK