- Coleridge-Taylor

- Kirill Karabits

- Cyprus

- Channel Classics Records bv

- Helmut Müller-Brühl

- Jan Dismas Zelenka

- Ginny Schiller

- Richard Hudson

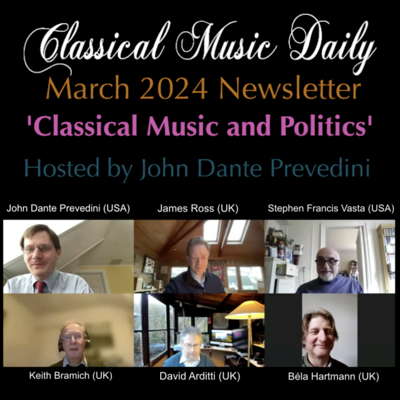

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Politics, including contributions from Béla Hartmann and James Ross.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

FRENCH ROMANTICISM

GEORGE COLERICK discusses orchestral music by

Berlioz, Saint-Saëns, Delibes, Lalo, d'Indy, Debussy,

Ravel, Honegger, Poulenc, Milhaud and others

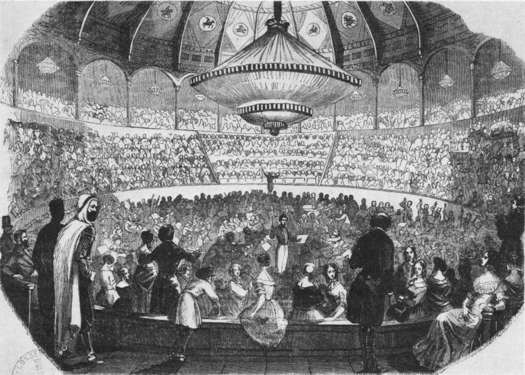

The classical sonata form, as developed also for symphonic and chamber music, is traditionally associated with Vienna, and the Germanic culture which strongly influenced musicians of neighbouring countries. This applied much less to the French, who were so committed to opera with its powerful social status. One man outside the French musical establishment was a prophet not accepted in his times. He would make a unique contribution, in effect combining the symphonic and operatic approach. Some of Hector Berlioz's structures were so original that he found new ways of describing them; his operatic Damnation of Faust he termed a dramatic cantata and his oratorio-like Romeo and Juliet, a dramatic symphony. He impoverished himself paying for what was needed to perform compositions, some conceived on a vast scale but which would have more influence upon other composers after his death in 1869.

Drawing of a concert given by Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) in Paris, published in the French weekly newspaper L'Illustration on 25 January 1845

Works for soloists, chorus and orchestra gained increasing attention in Paris by the 1870s. Among those very well known for oratorio were by Gounod, Franck, Saint-Saëns, Massenet and Fauré.

By the 1880s, Paris with two permanent orchestras was better equipped than London, and Wagner's achievements had increased interest in symphonic composition. César Franck was an admirer, an unobtrusive organist whose late attachment to composer Augusta Holmes may have inspired a late flowering and the most uplifting of French symphonies in which he is credited with applying Liszt's cyclical method of construction. Other outstanding works included the Symphonic Variations and the symphonic poem, Cupid & Psyche. They were harmonically so original that they attracted many disciples.

César Franck (1822-1890) - photograph by Pierre Petit

Camille Saint-Saëns, embracing all the traditional forms, was unusually versatile and seemed when young to be destined for the highest role. He worked to bring French music more into the European mainstream, but his efforts spread phenomenal talent too wide to satisfy many of his critics such as George Bernard Shaw. More interested in Bach than Wagner, his contribution to the repertoire was admirable, with ten concertos and the only French non-programme symphony, his third, to join Franck's in wide international acclaim. Living until 1921, he came to represent France's classic past.

Press photograph of Pierre Monteux conducting, with Saint-Saëns at the piano, at Saint-Saëns' planned farewell concert at the Salle Gaveau in Paris on 6 November 1913

France had a ballet tradition going back centuries associated with the court. In style, technique and even language, it had dominant influence in ballet schools abroad. Its earliest large-scale work to retain favour into our times was Adolphe Adam's Giselle, 1841, with a quaint scenario. Offenbach's Papillon was one of the century's greatest ballet scores but because it set out to ridicule Giselle, it is not performed in France except as a concert piece. In the following generation, Léo Delibes led the way in Sylvia and Coppélia, with its multi-national dance scenes; they influenced Tchaikovsky's future ballet scores. Édouard Lalo's Namouna was similarly successful, and some of his orchestral works displayed an attractive Spanish influence.

Édouard Lalo (1823-1892) in about 1865

Franck's pupil, Vincent d'Indy, wanted Frenchmen to study their musical roots, setting up a major school of composition. He was one of many who thought the influence of foreign composers had been too great over at least half a century. His style reflected the countryside and more restrained styles of beauty, such as the austerity of medieval church music. Ironically, he will certainly be remembered, if not for his theories but for a youthful work (1886), an invigorating symphony on a Cevegnol folk tune, with a very strident piano role which might have astonished Liszt if he had not just died.

Vincent d'Indy (1851-1931) in 1913

Among those that admired Wagner but thought music was becoming 'over-heated' was Claude Debussy. He worked towards new combinations of sound. Associating with great Impressionist painters of the 1880s, his aim was to match their revolutionary approach to shade, colour and outline with a delicate application of fresh tones and harmonies. Though his famed Clair de lune is an exemplary Romantic piano piece, his later melodies are generally less clearly defined, elusive, emotion expressed in subtle timbres. His musical personality was suited to piano and chamber works, like water colours, such as in describing a flaxen-haired girl or a submerged cathedral. As if painting in oil, his orchestral Impressionism reached to clouds, the surge of the sea, a festive procession, and the spirit of Spanish dance. He displayed interest in exotic scales and styles, as far as Javanese, and his Gollywog's Cakewalk was an early jazz parody.

Maurice Ravel's music has some parallel traits. Both sought new instrumental colouring; yet he used a more brilliant canvas and pronounced rhythms. Like Debussy, he avoided the strict symphonic forms and composed fine miniatures, notably for the piano. Born near the frontier in Basque territory, he was influenced by the colours and rhythms of Spanish music, and his Spanish Rhapsody typifies his unique mastery of orchestration. His style often has a distinct modal feeling more remote in time or place, with some delicate imitations of Asian music. Most talked about were his fashionable works, La Valse and Boléro. This with its solitary theme he used to ridicule for its repetitive 'non-musical' aspect, which partly explains its continued popularity.

The four years of the 1914-18 war were to give France the worst culture shock anyone could remember. Romanticism in all the arts had been a casualty. How would it be transformed or would it be superceded? That country's creative monde would hope to be in the vanguard of progress.

The Ballets Russes added to the appeal of Paris as the centre of European culture through the 1910s and 1920s, when many of the younger French composers were invited to contribute new works, notably Poulenc and Milhaud. Georges Auric, following success in ballet, revealed a talent for popular songs. Being a communist he was turning from what he called 'elitist music', finally reaching mass audiences by composing for films, many of which have become classics, such as the 1950 Moulin Rouge.

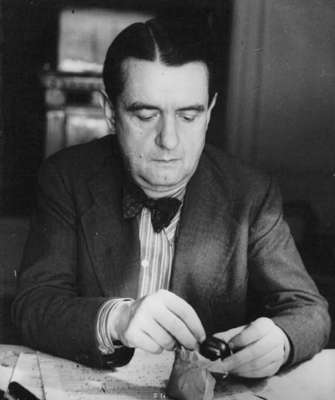

Georges Auric (1899-1983) in 1940

Several of the younger composers were criticising Debussy as 'lifeless' and Ravel as too refined. They wanted a link with popular cabaret and music of the streets, and Éric Satie's idiosyncratic, piano style charmed them. Behind the artistry, there is a sense of freedom and in his best known Gymnopédies, an unusual sense of relaxation. He influenced a youthful group called 'The Six', a loose association of 1920s composers including Poulenc, Milhaud and Auric.

One who faced both ways was Arthur Honegger, also inspired by earlier European and church music, pre-Romantic. Pacific 231 was once thought very modern with clashing chords and fragmented themes in a symphonic poem describing the acceleration of a railway engine. His oratorio, Joan or Arc at the Stake, combined several of the performing arts, and became well known in the West, with famous actresses in the spoken role.

French-born Swiss composer Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) in 1928

Francis Poulenc merged features of the two previous centuries' music into his style, graced with French wit and elegance. His Christian beliefs inspired the opera, The Dialogue of the Carmelites; his Gloria had pronounced rhythms which brought success as a new departure in ballet. He wrote four concertos, and was a distinguished performer of the two for piano. Poulenc was one of several who took the harpsichord out of the cupboard to which the nineteenth century had condemned it, exploiting its clarity and vitality in a solo concerto.

Swiss Frank Martin's scores were more radical, finding beautiful melody outside the familiar tonal system. His Petite symphonie concertante is a masterpiece in this style, and brilliantly exploits the differing sonorities of harpsichord, piano and harp, respectively exuberant, dramatic and languid. It is typical of his works, finding unique appeal in the merging of pre-Romantic and modern.

Darius Milhaud's style spanned a similar era, but to very different sound effects, rather dry. He had spent a few years in Brazil, which is apparent in some of his most popular works, such as Scaramouche and Boeuf sur le toit (Ox on the Roof). A visit to hear jazz at London's Palais de Danse in 1919 resulted in La création du monde (1923), a modern concerto grosso and perhaps nearer to symphonic jazz than anyone else achieved. He composed terse miniatures far from Romantic spaciousness, very brief operas and symphonies and helped to create a passing fashion in the use of polytonality, using two or more keys simultaneously.

London UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: ROMANTIC MUSIC

FURTHER INFORMATION: SWITZERLAND

FURTHER INFORMATION: ORCHESTRAL MUSIC