WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

- Worshipful Company of Musicians

- Albert Roussel

- Africa

- Vasks

- Jan Stulen

- Teatro dell'Opera

- Bruch: Violin Concerto No 1

- Peter Brathwaite

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

DVOŘÁK AND BRAHMS

GEORGE COLERICK explores the

folk music and other connections between

Antonín Dvořák and his friend Johannes Brahms

Bohemian is a word with mixed associations in our language. The Bohemian Girl was about a girl brought up by gipsies, and Puccini's were poor artists and girls of the Parisian demi-monde. Any association between our use of the term and the Czech folk idiom is obscure, though from the Middle Ages, Bohemia was so rich in musicians that many travelled abroad for work.

The mythological princess Libuše prophesies the glory of Prague, by the Bohemian painter Josef Mathauser (1846-1917)

Antonín Dvořák was born there not long after its capital, Prague, had been a bilingual city, and he grew up with keen awareness of Czech and German culture. If performances and teaching tied him to towns, his preference was to compose in a quaint country dwelling near the voice of nature. This is heard in some of his greatest works such as the Eighth Symphony.

He had the gift of spontaneity, so notable in his instrumental works; in this and other ways, there was an affinity with Schubert. He was one of the century's great melodists, the dominant influence being the Czech folk idiom, in particular the dumky rhythms, alternating slow and fast like the czardas, but often in nostalgic mood. He once wrote a complete piano trio around them, used in all six movements. By inclination, his style was rhapsodic and he often threw in more melodies than needed, especially in his chamber music. He was not inhibited from writing what some called 'café music', relaxing with instant lyrical appeal, such as his Op 97 Quintet, in that sense like Schubert's lightest works.

Born in 1841 to relative poverty, Dvořák was grateful for the Church's role in his musical education. He became skilled, playing violin or viola in a professional orchestra and while very young composed symphonic and choral works. There was much to absorb from established styles and techniques, especially Italian and Viennese. This, close at hand, he respected and, as he understood, it helped him to impose more discipline on his compositions. Fairly prolific from the start, he was aged thirty-six at the time he was befriended by Johannes Brahms, eight years older.

Johannes Brahms (left, in 1876) and Antonín Dvořák in 1882

Brahms' Romantic side and attachment to the German folk style are revealed in many of his more intimate works, and his songs nowhere more obviously than in his famous Lullaby. Yet the most famous quote about his music in general has been: Emotion recalled in tranquillity.

His symphonies display this, having great strength with internal tensions, the fulfilment of a Classical tradition. He had imitators, but no authorised school of followers.

There were enigmatic sides to Brahms' nature, belying his outer personality which tended to conceal emotions. Born in Hamburg, he had known poverty and whilst very young his family needed the money earned from his playing piano in disreputable places of entertainment. He may have had a taste for music at a distance away from the kind he would compose.

By maturity, he admired many different musical styles, and after a concert tour accompanying a Hungarian violinist, Reményi, was introduced to a more famous one, Joachim, with whom he remained life friends. Brahms specially liked Goldmark's Rustic Wedding Symphony, leading to part of a creative interest in Hungarian music. This might surface surprisingly in compositions, such as whole movements in his Violin Concerto and Opus 25 Piano Quartet.

It was a novel idea to compose a set of Hungarian Dances, musically letting his hair down. As many as sixteen were based on what he assumed to be authentic melodic sources, and the last five were probably his own. Aranged four-handed for pianos they would be a treat for music students, especially when compared with typically 'boring teaching exercises' for middle-class daughters to practice in the home. By any standards, they were earthy, brief and very exciting. In the 1860s, they set a new fashion. Brahms' personality was apparent within them, but he enjoyed this brief holiday from four-square German rhythms. He was interested in the popular forms of Bohemian and other Slavonic music and even edited Dvořák's Dumky Piano Trio and other of his works for publication.

Dvořák was of the second generation of Romantic composers who could not fail to be impressed by Wagner's work, so that Brahms was to become a valuable counter-weight. Unlike most composers of his time, Dvořák was devout, essentially a family man, unsophisticated and determined to remain close to his peasant roots. Brahms, a city man, intellectual and agnostic, could seem insensitive, even falling asleep when Liszt was playing. Aloof but no snob, he treated the talented Dvořák as friend and protégé for the remaining twenty years of his life. The empathy between them was instant, and being a bachelor, he wanted Dvořák to come and live in Vienna, so that he could enjoy life with a large family.

Brahms had migrated to Vienna where he disliked being lionised by musicians as their leader, or by public admirers. He was at pains to choose his own friends and first met Dvořák whilst on a committee of music judges. Dvořák's Moravian Duets had first impressed Brahms who then took his work to the Berlin publisher Simrock. This was a decisive event for the younger man who had enough spare material for several composers, or so Brahms thought. Later he introduced Dvořák to the Hungarian Josef Joachim who advised both men on their respective violin concertos.

The Joachim Quartet. From left to right: Carl Halir, Robert Hausmann, Joseph Joachim and Emanuel Wirth

The popularity of Brahms' Hungarian Dances resulted in Dvořák orchestrating some, and Simrock suggested his following with comparable sets of Slavonic Dances. These quickly became his best-known compilation; of the sixteen, half were Bohemian in style. They were longer, more elaborated than Brahms' and Dvořák used his own melodies entirely. Both men also composed original works in the manner of gipsy songs.

Dvořák from the start of his career specially revered Brahms who had greatly impressed Schumann with taut, disciplined instrumental music whilst still a very young man in the 1850s. In contrast Dvořák's approach to composition was very spontaneous, discursive, Slavonic. Brahms' attachment to folk music was more apparent in his songs than in his symphonies.

Dvořák had already composed five symphonies, the early ones tending to ramble, by 1876 when he met Brahms, who had none published. This was because, as he said, he felt in the shadow of Beethoven. Eventually the critics assumed that his second had influenced Dvořák's numbered six. They are both very lyrical but the Dvořák, dispensing with an introduction, builds up with a great sweep which was unique. The third movement has a Czech rhythm, a furiant of rare pace, leading to the most satisfactory conclusion he had reached. Until then, endings had been his particular symphonic problem. Resemblances to Brahms' were superficial.

Brahms' symphonies were very tightly structured, and suspenseful. Dvořák was aware he stood to gain much by studying the formidable techniques of his friend. Resemblances to Brahms' style are most striking in three subsequent works: his opus 65 Piano Trio, melodically and in the percussive use of the piano, and perhaps the greatest of his chamber works, the opus 81 Piano Quintet. His Seventh Symphony was composed in years of unusual personal stress, more impassioned, reflective, with some melodies which might be mistaken for Brahms'. Critical opinion often praised it for being more 'profound' but it is now regarded just as an interesting departure in style, none the less valuable for that.

Composing a cello concerto presents a problem of the instrument's pitch, much lower than the violin's, against the orchestral sound. Dvořák overcame this, and Brahms recognising its inspiration said he would have done likewise if he had realised it was possible. That was modest because some years previously, he had composed a work for violin and cello, probably the greatest double concerto of the century.

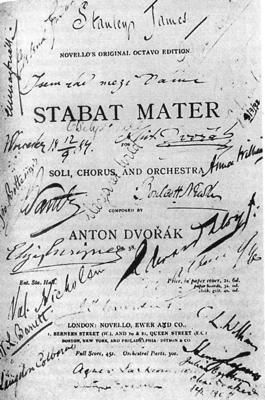

Both men wrote distinguished choral works and Dvořák's Stabat Mater reflected his own family bereavements.

The title page of Dvořák's Stabat Mater score, signed by Dvořák and members of the orchestra following the performance in Worcester, UK on 12 September 1884

By the time Brahms died in 1897, Dvořák had ceased to compose non-programme music, symphonies and instrumental, to concentrate on symphonic poems and opera, none of which Brahms had written.

London UK

FURTHER INFORMATION AND ARTICLES ABOUT DVOŘÁK

FURTHER INFORMATION AND ARTICLES ABOUT BRAHMS