- Prince Igor

- Hans Seeling

- Franz Clement

- Copland

- Belgrade

- Dexter Drown

- Mozart: Violin Concerto No 4 in D

- Jessie Ann Richardson

CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

ARTICLES BEING VIEWED NOW:

- Régine Crespin

- Hector Berlioz

- Ruth Railton

- Marián Varga

- Profile. A Very Positive Conductor - Paul Bodine talks to Los Angeles Opera's Music Director Designate, Domingo Hindoyan

A CALL TO ACTION

GEORGE COLERICK discusses early Romanticism,

with particular reference to Schubert, the piano,

Schumann and the development

of the symphony orchestra

At the start of one chapter in BBC TV's classic series, Civilisation (1969), Kenneth Clark is standing in an elegant library in the finest eighteenth century style. This he uses to symbolise the Enlightenment, a refinement of human thought: Western Europe's neo-Classicism in the creative arts, most familiar in the music of Mozart. Its style was, as Clark says, symmetrical, balanced, consistent and enclosed. To nine tenths of European citizens toiling in poverty until an early death, this elegance and wisdom was meaningless. Yet the writings of enlightened men seeking just, reasoned solutions to society's problems would lead to a cataclysm, the overthrowing of the feudal world, so that 'modern history' is said to start with the French Revolution, leading into the nineteenth century.

An anonymous oil-on-canvas painting of the storming of the Bastille and the arrest of Governor M de Launay in Paris on 14 July 1789

Earlier in this series on Civilisation, Clark had praised symmetry and consistency in the arts, but he recognises they are the enemy of movement, for which mankind has an irresistible urge. Some will see the enclosed world as a prison from which to break free. Those who wrote about it around 1800 were the early Romantics.

From the library, Clark hears a challenging call to action. It is the freedom theme for the political prisoners in Beethoven's opera, Fidelio. He walks into the next room, opens a door, stepping out into a splendid Classical portico, to be confronted by a turbulent sea. The Romantics were to be inspired by nature, the sea being dynamic manifestation, often to be felt in the works of nineteenth and especially twentieth century composers.

An 1804-5 oil portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) by Joseph Willibrord Mähler (1778-1860) from around the time of the opera Fidelio

Classicism was cosmopolitan, designed for European aristocracies. With some exceptions, nineteenth century composers increasingly became independent of the courts and of royal patronage. Their new audiences were more familiar with popular and folk music and dancing, which would influence Romantic expression. Franz Schubert (1797-1828) had no connection with the Viennese court and his style would develop under the influence of his native Austria's folk idiom. He moved instinctively away from the sharply defined melody of the Classical period to a smoother line, and more flexible rhythms. He also belonged to the first generation brought up with the advantage of composing on what we hear as a 'modern' piano, with its capacity for legato. If the piano was the most spectacular, other instruments were being given wide opportunites for virtuosity, especially the violin which had performed a valuable solo role in folk music.

The 1899 oil-on-canvas painting Schubert at the Piano (1899) by Austrian symbolist painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918)

The improved instrument with its sustaining pedal increased harmonic possibilities, so it served for what had always been lacking: the ideal accompaniment to the voice. Schubert often exploited the piano to perfection, heightening the emotive power and Romanticism's fashionable themes, love, nature and death, were prominent. The words were no longer just a pretext for a good tune, the lyrics matching closely to the melody. This effectively created a new genre of distinguished art songs (Lieder) and song cycles, and many German composers would follow: Schumann, Brahms, Wolf, Richard Strauss and others: a repertoire of many thousand songs.

Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) by an unknown photographer, published on a 1910 postcard

Schubert scarcely revised his work, and he used the terms impromptus and musical moments for short compositions. Later composers would use titles such as prelude, study, intermezzo, ballade or those describing dances. Even the early compositions of Liszt, Schumann and Chopin seemed to inhabit a totally diffferent sound world from that of two decades earlier, freer in structure. Composing on the improved pianos, they experimented with chords and harmonies in ways previously not possible. Chopin never completed a score without including piano, whatever the combination of instruments, and his music beyond expressing a mood or atmosphere was always abstract in conception. By contrast, Liszt and Schumann favoured an expressed 'programme', mainly literary, a new trend which became fashionable. Schumann composed great song cycles and his most characteristic piano work was Carnaval, invoking characters out of his own fantasies. This was related to his being also a literary spokesman for the 'new German music'. Except for one by Schubert, he initiated a musical form, the piano quintet, combining piano with string quartet. This was successfully followed by Brahms, Dvořák, Franck, the American Amy Beach, Elgar and several others.

American composer and pianist Amy Marcy Cheney Beach (1867-1944)

Rubato is a technique dependent on the sensibility of the performer, the slight delaying (or precipitation) of a note, which can be very emotive. This was most apparent in the piano playing of Liszt and Chopin, but also in the virtuoso conducting of orchestras, too large by the 1830s to be led as previously by the principal violinist.

Thanks to the dominance of Vienna in instrumental music, Mozart had known most of his leading musical contemporaries, and their compositions tended to sound similar in style. Half a century later, the musical personalities of the younger composers were developing in very distinct ways, increasingly easy to identify. This trend was part of Romanticism's cult of the individual. It had reached its first peak by the 1850s, by which time Mendelssohn, Chopin and Schumann were deceased. In opera and concert hall, its development as far as our own times will be the subject of future articles. Its most sophisticated medium has been the symphony orchestra whose development has been miraculous.

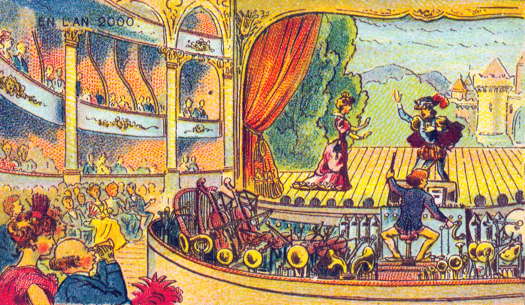

'France in the 21st century': a theatre performance with an orchestra of mechanical instruments, with a human conductor turning the crank, by Jean-Marc Côté

For much of history, playing instruments simultaneously would have sounded an excruciating noise. New inventions and technical improvements gradually led to combinations which were pleasing. By 1750 that could include strings, percussion, flutes, oboes, bassoons and, restricted without valves, trumpets and horns. It later acquired clarinets, trombones, tubas, bass drum, harps and improved trumpets and horns. Some composers have since the late nineteenth century added saxophone, celeste, piano or other instruments for special effects. With its power, its depth, multi-coloured sound and range, the modern symphony orchestra has had a major role in spreading a unique melodic and harmonic system into the New World, then to societies which have their own distinctive musical traditions. Smaller bands with less variety of instruments have played a part, especially for popular forms of music. As Kenneth Clark concluded, Romanticism's exciting journey continues and we don't know exactly where it will lead.

London UK