- Elisabeth Chojnacka

- Naxos Rights Europe Ltd

- Naxos Deutschland GmbH

- conferences

- Michele Carafa

- Mark Dover

- Debussy: String Quartet in G minor

- Alexander Gemignani

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

A Spiritual Journey

RODERIC DUNNETT takes an extended look at the career of English composer Ian Venables, and listens to a recent performance of the orchestral version of his Requiem

Ian Venables is universally recognised as one of England's greatest composers. And this recognition has only been further enhanced by the emergence and recordings of his setting of the Requiem Mass.

He himself would be surprised and touched by the reception of the Requiem, his largescale new choral work, whose craftsmanship and beauty have been widely praised. It has featured on Classic FM. On BBC Radio 3's landmark programme Record Review it's received the highest praise, being hailed by Andrew McGregor as 'a modern classic '. BBC Music Magazine recognized its 'ability to stir the more tender emotions'. In the provinces it has been dubbed 'a flawless triumph.' Choir and Organ judged it 'both moving and consoling'. 'Simplicity becomes strength: small motivic cells gain stature through repetition and elaboration', wrote The Gramophone.

The last emphasises an essential point: the way Venables fashions small detail into a coherent whole, extracting from it significant, recognizable patterns which form the basis of a deeply satisfying, bold undertaking.

Ian Venables. Photo © Graham Wallhead

But no surprise in that. Venables has long been acclaimed for his more than a dozen song cycles, which have appeared on more than ten magnificently memorable discs. His choice of poetry is shrewd, exquisite, and sometimes sensational, and time and again, his songs are inspired and magical. 'A song composer as fine as Finzi and Gurney' (also The Gramophone) was just one more of the accolades he has drawn. The earlier On the Wings of Love (superbly recorded by tenor Andrew Kennedy, Naxos 8.572514) and 'Love lives beyond the Tomb' (with Graham J Lloyd, Mary Bevan, pianist Allan Clayton and the Carducci Quartet, Signum SIGCD 617) are two superb examples. Likewise The Song of the Severn (again with the Carducci), the last two reflecting his notable ability to set songs with not just piano accompaniment, but with collective or solo instruments - clarinet, viola - as well.

Ian Venables: The Song of the Severn. SIGCD424. © 2015 Signum Records

Indeed Venables wrote a number of instrumental works, particularly early in his career, and these several he has acknowledged in his opus list, and all have been rapturously admired. They begin as soon as opus 2, an 'Elegy' for cello ('Poem', for cello followed and soon a Sonatina for oboe). Pieces for violin, flute and then viola followed, the last immediately preceding his Piano Quintet - Op 27, recorded memorably by Mark Bebbington and the Coull Quartet on SOMMCD0101 - and, as mentioned below, a brilliant String Quartet, its chromaticism somewhat at odds with his normal idiom, and one of his very finest; along with a 'Canzonetta' (opus 44) for Quartet abetted by a beautifully conceived role for clarinet. His Rhapsody for organ, both in tribute to, and having much in common with the considerable output for organ of, Herbert Howells, is in my opinion one of the most absorbing and enchanting pieces written for the instrument last century this side of the Channel and of the Atlantic.

He has even not been averse to making translations of one or more of his songs for instrument. This is surely a practice he might continue: they could make superlative test pieces or practice items for students.

But it is his songs (or as he prefers to call them, to distinguish them from other genres ,'art songs') that have brought him such unique renown. His initial song settings span opus 6 to 16, and he was already gaining a reputation. With the cycle 'Invite to Eternity' he was focusing on the unhappily incarcerated Cambridgeshire (Peterborough)-born poet John Clare (1792-1864); later he added Alfred, Lord Tennyson - a poem mourning the youth he loved, Arthur Hallam, who died aged twenty-two - and Edward Thomas, Robert Frost, Yeats, Cavafy and Lorca, plus the visionary countryman George Meredith, Robert Louis Stevenson (from A Child's Garden of Verses), and Walt Whitman (a complete cycle for his bicentenary); but also, often intriguingly, a number of lesser-known poets, both contemporary and historic, to his portfolio.

Ian Venables: Song Album.

© 2004 Thames/Elkin

Ivor Gurney - his poetry at the heart of Ian Venables' cycle The Pine Boughs Past Music - lies somewhere between the two, but is now, not least thanks to Venables' own efforts, gaining, meteorically, a long-delayed reputation. Remember This is likewise throughout a setting of Andrew Motion, who is himself acutely aware of, and positive about, both Housman and Edward Thomas. The Song of the Severn includes, for instance, John Masefield - two poems, one particularly exuberant - and Gurney's bosom pal in youth, F W (Frederick) Harvey. Like Clare and Gurney (and Motion), 'Songs of Eternity and Sorrow' offers (here, four) poems focusing on a single poet, A E Housman, both of them what might, given Housman's own life and predilections, be termed 'gay poems, and boldly sets two of Housman's most self-revealing poems, the angry 'Oh who is that young sinner' (... 'tis a shame to human nature, such a head of hair as his'), and the deeply moving 'Because I liked you better' (than suits a man to say), both taken from the posthumous collection More Poems: the whole is dedicated to the Worcester-based Elgar scholar, Jerrold Northrop Moore.

'Sometimes', Ian has fascinatingly opined, 'I wonder whether I choose words or whether they choose me!' In Through These Pale Cold Days he ventures, after some reflection, to set poems, at times angry, at others warm and caressing, from or about the First World War: hence Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Isaac Rosenberg and the Reverend Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy ('Woodbine Willie'), spiritual comforter of so many, all figure, as well as - an inspired idea - a plangent, expressive viola. He has written, with typical disarming modesty:

The main difficulty is that the vast majority of war poetry is so starkly realistic and uncompromising. Perhaps, this is why there have been few [Great War] poems set to music. It is for this reason I began to question whether setting such words to music might be an affront to the poetry itself.

Nonetheless, with typical modesty, inevitably and rightly, after much reflection, he went ahead, and produced a work permeated by menace but also deep intensity and empathy. Portraits of a Mind is a cycle specially composed for (and commissioned by) the Ralph Vaughan Williams Society as part of the 2022 celebrations of the revered composer's 150th birthday. Venables was touched and delighted to be involved in such a substantial - and highly honored - way.

There were earlier masterworks too: several visionary pieces, for piano (recorded by Graham Lloyd on Naxos 8.573156), or indeed for chamber ensemble, including a much admired Piano Quintet and (in my view), a magnetizing String Quartet, his opus 32 (1998, Signum SIGCD 204) which reflects, enthrallingly, Venables' fascination for Shostakovich early in his career. One should add his nine-minute Rhapsody for Organ Op 25 (1996), a wonderfully empathetic work in memory of, and indeed drawing upon, Herbert Howells. It has been twice recorded, by former Worcester Cathedral organist Adrian Lucas - Regent Records REGCD 159 - and on the present disc, alongside his now orchestrated Requiem.

With both live performances and especially his substantial output recorded on disc, Venables has become known and deservedly acclaimed across Britain and beyond. No wonder, then, that on a personal note he was chosen by Bryce and Cynthia Somerville to compose, most aptly, a setting, as a short choral anthem, of (just) the initial Requiem movement, in commemoration of their late mother. He is no stranger to composing for choir. 'God be merciful' is included with the Requiem alongside works by Howells on this latest Signum disc.

The fullest and possibly most perceptively appreciative comments of all, with admirable attention to (and understanding of) detail, finely worded, intelligently supportive and immensely sensitive to the material and its intention, came from John Quinn, the Midlands-based doyen of Seen and Heard International. 'A work of great importance and eloquence ... Profoundly expressive', he began. And notably, 'In this orchestration the original organ part is expertly re-imagined in a highly effective fashion.' 'The benign influence of Howells (and Duruflé) seems to hover over Venables' Requiem, especially in the harmonic language.' 'The music shows a great sensitivity to the words.'

Ian Venables at the grave of American Romantic composer Samuel Barber, a significant influence

The 'Offertorium', Quinn observes, 'is one of the most impressive movements in a very impressive work.' The 'Pie Jesu', 'softly accompanied, is disarmingly lovely.' The passage at 'Hodie memoriam facimus', at times significantly fortissimo, 'offers a choice example of Venables' skill in word-painting.' Other more openly and, regarding the performance, dramatic, even fearsome sections (for example, the later allusion to 'Dies Irae' (passingly: though not a section in itself) - the work is not averse to fortissimo - are aptly 'implacable', 'remorseless', or else of 'subdued resignation'. Quinn concludes by proclaiming 'in Venables' Requiem we have, I believe, a masterpiece.' 'I venture to suggest this is Merton [College Chapel Choir's] finest achievement to date.' So he sees this Delphian recording as 'outstanding in every respect', also finding a place high on his own list of recommendations for 'Recording of the Year'.

Venables himself has explained instructively, illuminating the idea behind the final 'Lux aeterna', that the concept of 'Eternal Light' has in his eyes 'a transcendental resonance - one that connects our inner world with the spiritual world that lies (as he puts it) 'beyond the veil'. Hence, Quinn finds, here the music to which he sets the text is radiant and illuminated: 'At the end his Requiem doesn't achieve a hushed ending [as do, for instance, Fauré and Duruflé]. Instead, the music gets louder and one has the sense of moving with hope, and confidence, towards the light.'

A significant development took place when Venables was adopted as a house composer by Novello & Co - Music Sales, now part of The Wise Group - whose remarkable sixty-plus music companies have bases not just in the USA, Japan, Australia and South-east Asia, but across Europe. Thus the potential for Venables' vocal, choral, chamber and instrumental works - his Violin Sonata, Op 23, was performed this year in Taiwan - reaching a wider international audience must be considerable. And at this stage of Venables' burgeoning fame, it could not be more deserved or timely.

Ian Venables: Requiem Op 48 -

score for choir and organ

published by Novello & Co

Just as his extensive appearances on Novello's preeminent list is an indication of his stature, so the blossoming CD (or download) recordings speak for themselves. Delphian, Somm, Signum, Regent and EM Records have all played their part in making Venables' music, not least his masterly song cycles - settings of numerous well-chosen poets, and in certain cases, ones he champions and believes should be better known, some short-lived. (An obvious example is John Addington Symonds, 1840-93.) Perhaps most notable is his appearance - notably with 'On the Wings of Love', 'Venetian Songs - Love's Voice' - on Naxos (8.572514), the recording company which still enjoys perhaps the widest distribution across all countries of the world. No surprise, either, that the hugely knowledgeable and influential Presto Music shop has classified him as 'something of a spiritual heir to lyrical songwriters of the [early twentieth century] English school' - known as the English Musical Renaissance.

Venables had several times indicated that he had no intention of following up by composing a full Requiem. Indeed, he initially asserted, 'emphatically not!' ... yet somehow that initial refusal ended up as a grateful 'Yes'. He adds 'I've only (in my songs) before set words - poetry - in English.' And indeed, when he previously composed his three bracing or compelling anthems, 'O Sing aloud to God', 'Awake, Awake, The World is Young' and the latest, 'God be Merciful' (opus 51 - it sets lines from Psalm 67 (the Canticle known in Latin as the 'Deus Misereatur') - he has each time inspiringly risen to the task of lending power to the words by his music.

The Requiem Mass, or Mass of the Dead (the Catholic Missa Defunctorum), its opening text derived from the Old Testament book of Esdras, chapter 2, is most usually set in Latin, although the fully extended version, known as the All-Night Vigil, set twice by Rachmaninov, is in Church Slavonic. Longer or shortened, it plays a role in many related liturgies, hence is encountered sometimes also in the languages of the Eastern Orthodox rite, such as Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania.

In the Western church, after many centuries of chanting just in Plainsong, versions in elaborate contrapuntal form began to emerge with Dufay and Ockeghem, Brumel, Josquin, Pierre de la Rue, Richafort, Escobar, plus from the next generation, Morales - by which time they had become a staple of the Roman Catholic rite - and from the next the sublime setting of Victoria. From Gilles to Campra to (very obviously) Mozart and on to the massive conceptions of Cherubini and Verdi, a firm tradition was established, and, as with the popular settings of John Rutter and Andrew Lloyd Webber, both very acceptable, has continued till this day. Like the last, Fauré and Duruflé lie at the more contemplative end, as does the present work, one as enriching as both the last two.

However, perhaps surprisingly and unexpectedly, Venables found the idea of entering this great tradition and bringing to birth a whole Requiem setting beginning to leaven, and began working on it - several movements of the Mass for the Dead, although not yet the whole - throughout 2018. Aspects of a possible approach occurred to him quickly. He has said:

I firmly believe that the words employ images which can be reflected in the music. By January that year I had finished one substantial movement. In those earlier stages I hadn't approached either the 'Pie Jesu' or the 'Dies Irae'.

These would appear in the final text, though not as a whole Berliozian or Verdian movement.

But I was conscious that there are a number of terrifying places at several points in the text - 'the lion's jaws' ('de ore leonis'), visions of Hell and plunging into darkness.

Then an event occurred which precipitated the next stage.

A good friend died, and it was with this in mind that I set about writing a 'Pie Jesu'.

Fauré's own observation surely accords with Venables' intentions:

Everything I managed to entertain by way of religious illusion I put into my Requiem ... dominated by a very human feeling of faith in eternal rest.

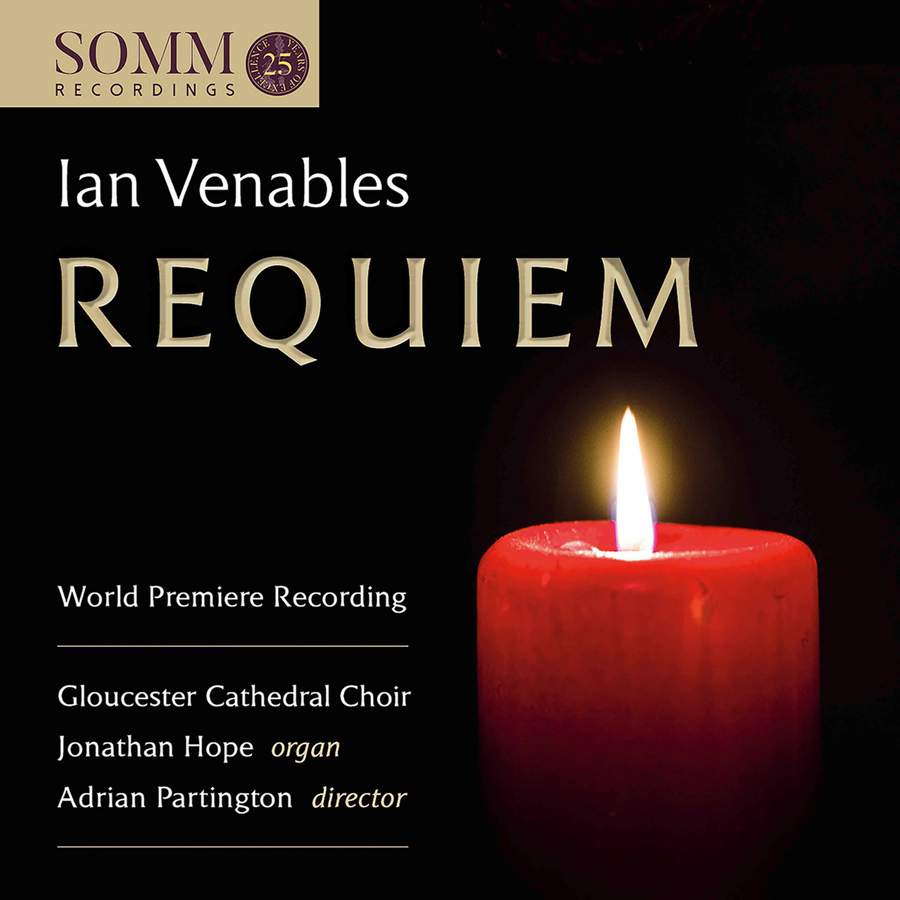

In late 2018 the Venables Requiem, at that stage without the two final movements, was given its premiere in Gloucester Cathedral by the choir with a fine organ accompaniment, directed by Adrian Partington. Upon completion Partington with his choir recorded it on the Somm label (SOMMCD 0618), issued in summer 2020. Beautifully and empathetically sung by men and boys, and ideally paced by the conductor, on appearance it was immediately hailed as a major achievement and contribution to the repertoire, one that can be taken up with pride by other cathedrals and also choral societies across the country.

SOMMCD 0618. © 2020 SOMM Recordings

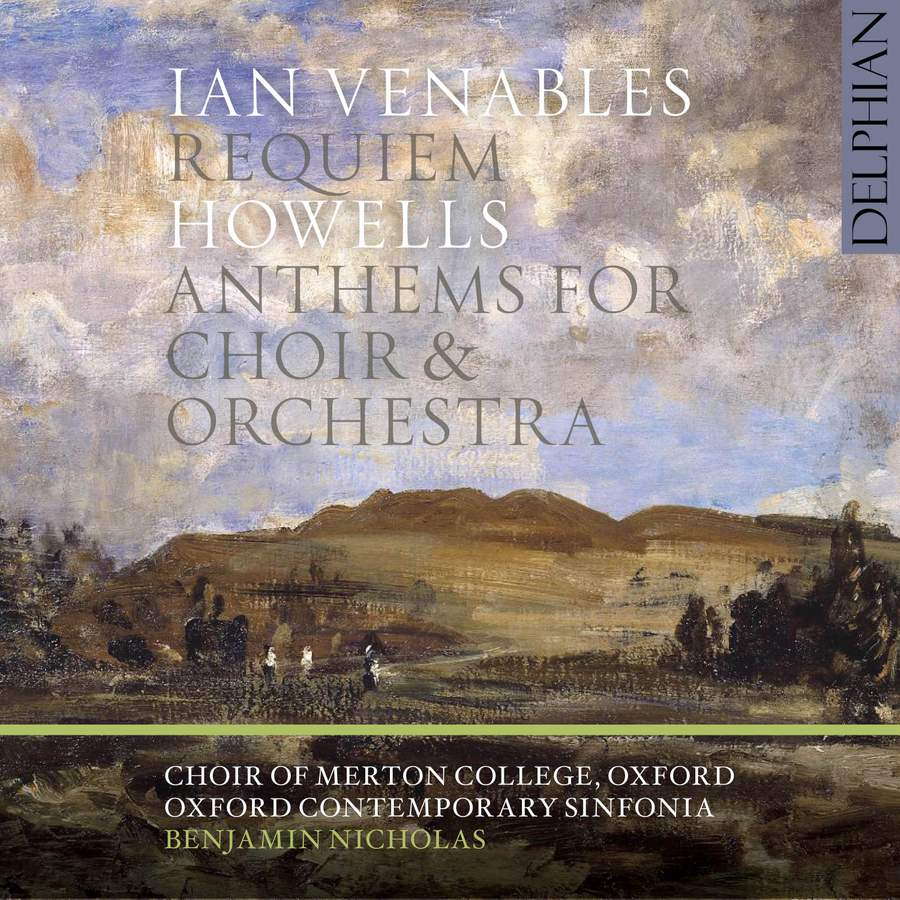

Venables' orchestration in itself, composed for the Choir of Merton College, Oxford under the ever-inspiring direction of former Tewkesbury Abbey Director of Music, Benjamin Nicholas, and initially performed there, yielding its ultimate first recording (Delphian DCD 34252), issued in November 2022, has been praised by reviewers from the most prestigious magazines and newspapers, and is indeed a major, patently the most significant element of this utterly brilliant recording. (One doubts not that others will follow.) One commentator proposed 'Venables' Requiem, initially conceived for choir and organ, is here presented in new clothes ... an orchestral version which adds colour and texture ... [it is] by turns moving and consoling to the living'.

The disc also includes well-known anthems by Herbert Howells, who along with Gerald Finzi is undoubtedly an influence or at least an inspiration to Venables. Indeed he himself has suggested:

I believe that melodically I owe something to Finzi and harmonically to Howells. With regard to the latter, there are obvious vertical harmonic similarities (such as the use of false relations, exotic compound chords and gnarled chromaticism).

Howells' 'O Pray for the Peace of Jerusalem', 'Like as the Hart' and (less familiar) 'House of the Mind', all in new arrangements for strings, but the last with viola and string quartet added, have yielded performances on disc which are deeply moving - especially the last, which has been specially applauded for its unusual drawing upon the viola, a device Venables has, as it happens, used elsewhere to specially fine effect.

The second is most fabulously recorded (with organ) by George Guest and the Choir of St John's College, Cambridge, on 'Twentieth Century Church Music', a little-known Argo disc (4832430, circa 1962), which also includes the astounding (to some, disconcerting) first performance of Tippett's electrifying Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis (composed for the College), Bairstow's 'Let all mortal flesh keep silence', and most inspiredly of all, John Ireland's (narrowly pre-Great War) 'Greater love hath no man'.

Merton's Delphian recording brought new discoveries. Sixteen separate microphones were set up in the spacious college chapel. Venables says:

The recording took me on a journey I would never have thought of. I hope my music has reflected the words of the text ... Kenneth Leighton [and many other composers, including Britten] used to get up in the morning and work till lunchtime. My approach and timing are somewhat different.

Of importance to him was especially the challenge of composing the 'Offertorium', which is a long text and generates a long movement. But the concluding Libera me is, he says, the emotional heart, or perhaps the apex, of the whole work, and this has been commented on or speculated about by many of his admiring critics.

DCD 34252. © 2022 Delphian Records Ltd

It's appealing, too, to reflect that the good Lord would not have been anything but delighted by this bold - and stunningly successful - undertaking. The most recent performance of the newly orchestrated Requiem took place in a concert at Great Malvern Priory, with a first half conducted by Kenneth Woods who, the programme of this year's Elgar Festival pointed out, was hailed by Gramophone Magazine as 'a symphonic conductor of stature'. 'The ESO and Woods were flawless' declared The Classical Source. 'Kenneth Woods conducted an on-fire English Symphony Orchestra' (Chris Morley in The Birmingham Post). He is something of a Mahler specialist, admired not least for this season's Des Knaben Wunderhorn, Kindertotenlieder, Rückert-lieder and Symphony 2 (the Resurrection Symphony), plus somewhat earlier, in the United States, applauded notably for the completed Mahler Tenth Symphony.

It remains a splendid idea for Ken Woods, American-born, but living for two decades in the UK, whilst still in demand as a conductor across the Atlantic (Washington, Cincinnati, the Aspen Festival, Canada), and in addition a stupendous cellist, to take on the Artistic Directorship of the Elgar Festival, and to bring his much improved, polished English Symphony Orchestra, which also offers a host of training events for ensemble - brass, wind etc - to Malvern for this concert (and a further event, for strings, the next day).

The quality of the orchestral playing is top-class, astonishing and miraculous under his leadership. Throughout the opening half of the concert, which included four other pieces - two of them works by Elgar - it was Woods' pacings and meticulous control of balancing which impacted at every point. And both showed most of all in Stephen Shellard's superb, subtle and conscientious approach to ensuring Venables' Requiem achieved the quality of presentation it deserved.

Stephen Shellard. Photo © Michael Whitefoot

Throughout the Requiem, Venables reveals his particular, superb musicianship by his use of small and larger motifs, which he develops and varies in numerous subtle ways. There is, it seems, a base of Plainsong in the patterns he unfolds.

The sopranos, perhaps the upper voices, initiate the Kyries, where already a descending or falling fourth is added to the mix, in which a soprano solo is used sparingly and beautifully. The genuine pianissimo of the orchestra here was in itself wondrous.

The tenors - laudably and perhaps unusually strong as a section - launch the 'Offertorium' - indeed an extensive movement - with the plainsong-like pattern, joyously. As the text grows ominous, exploding brass underline the acute tension. There is a transition to the word 'Osanna', beautifully scored for violin, cello and clarinet (I assume) soli. A telling ostinato underlies the 'Hodie' passage; and 'we believe' - 'credimus' - is upheld by firm, but not overwhelming, brass.

The demeanour of this setting - intense, inspiring, deeply moving - has already been established since the very Prelude. But also brisk and arresting. The acoustic of Great Malvern Priory, dedicated to the Virgin Mary and which dates back to the second decade of William the Conqueror's reign, had already played its part: what a marvellous sound it enabled Shellard to generate in the exciting Sanctus, as galvanising as the famous loudly chanted Agincourt Song. Every chord was perfectly placed, its evolution logical and appropriate. A passage for basses only was arguably surpassed by a further extension for tenors and basses together. But could anything be more dramatic and imposing than the treatment of the text 'Hodie memoriam facimus'?

Likewise the most insistent assertions of belief are repeated to great effect. Any attempt to relate Venables' Requiem directly with Fauré or Duruflé fails, unlike with the admittedly quite tender and impressive Andrew Lloyd Webber version. A more apt comparison, given the range of emotion and expression, might be the choral works of Poulenc. But Venables is in thrall to no other. His structure, for all the similarity of movements, is entirely his own. And it speaks mountains for his gifts as a choral composer, of a quality to match his superlative 'art' songs - his settings of Housman, Symonds, and in one case the extraordinarily sensitive, possibly revealing Pierre de Sponde (1557-95), who wrote love poems (The Amours, which he later disclaimed but were published posthumously in 1597 with Poésies posthumes), and later penned considerable religious tracts.

Others have aptly designated Venables' 'Agnus Dei' as 'a plangent, subdued prayer for mercy.' The pattern is different, or at least further developed here, essentially or partly suggesting, though not imposing, a minor key. Material from earlier sections opens up into a rising and falling pattern, with the choir's two lower voices leading and the upper ones following.

Here it's appropriate to mention the wondrous ways Venables uses what have been described as 'gorgeous harmonies', elegant counterpoint spread across the parts, and indeed canons, subtle or disguised, or more prominent, to give different passages effect - always to some degree responding to text. In the 'Agnus' a trumpet line - whether solo or with a partner: the score stipulates three - plays a striking melody, the sensation by now being more like a major key. The movement is, like all the others, beautiful, intense and, in this case, confidential. Like the 'Pie Jesu' it calls for highly sensitive orchestral playing, and this Stephen Shellard inspiringly elicited from his splendid Worcester Cathedral Chamber Choir, the Saint Cecilia Singers and three soloists, the response from both choir and attentive ESO players alike feeling perfect and unfaultable.

By way of further congratulation, Woods' mastery of rehearsal, leadership and delivery shone through the other four items in this well-managed first half: a piece by the fine, relatively recent, exploratory American William Grant Still (1895-1978), always an intriguing and attractive composer; a new if shortish (nine-minute) piece, The Vision of Piers Plowman by Michael Berkeley, Composer in Residence to the 2023 festival, basing his three-movement Suite on music he composed for an unusually long-running series on BBC Radio 3. Initiated by an attractive, memorable melody, it aspires to capture or illuminate 'one of the great allegorical poems of the Middle Ages'. Plus cynical and satirical, the book a 'mixture of theological allegory and social satire', Berkeley neatly adds; as well as a highly entertaining journey, composed seemingly in the reigns of Edward III and Richard II. The music's tone is consciously a bit sour (as Langland's invented character was, Berkeley perceives), a short work admittedly not a patch on the ridiculously under-revived, much more extended choral work of that name by the late Gerard Schurmann, written for the Gloucester Three Choirs Festival. Add to these a late miniature by Elgar, 'Mina', named after one of his beloved terrier dogs.

In fact Elgar had the lion's share of the first half, Woods eliciting an alluring performance from the ESO of the quite graphic, rarely heard incidental music suite King Arthur: here cheerful, making some dramatic use of ostinatos, but with Woods careful to avoid allowing such sections to overbear; others - an early clarinet solo stood out - easing down, almost lumbering. The 'Battle Scene' is not all explosive, but interestingly starts and ends quite softly. There are pianissimo strings at times, and the double basses beat out something very close to what we know in Elgar as 'nobilmente' - witness his Pomp and Circumstance Marches. Indeed there peep through musical cousins of other Elgar works - not actually borrowings yet recalling some that had gone before: 'Falstaff', even 'Gerontius'; or one still to come: the 'Nursery Suite'.

Talking of drama, at the end of the Requiem, Ian Venables proves he knows just how to elicit vivid, dramatic, and even aggressive music from the last two movements he chose to set: 'Libera me' and 'Lux aeterna'. The optimism and spiritual release of the last was something he felt, deeply and keenly, should form the conclusion to, even the climax of, the whole work. He sought to express the words, latterly, 'in more comforting and consolatory terms'. Indeed, hope, perhaps even of the afterlife, should prevail. Thus it is in a spirit of rapture with which he moves to his conclusion.

But he adds:

The 'Libera me' was the greatest challenge I faced: the text is very long and consists of several dramatically contrasting parts; this certainly posed a musical challenge. Looking back on it now, the 'Libera me' has turned out to be the most musically dramatic and expressive movement in the whole work: it is also the longest!

Ian Venables.

Photo © Graham Wallhead

Venables' deployment of the organ, not least here in the 'Libera me', is particularly inspired - all the apt registrations and combinations were devised by the excellent, to a degree unsurpassed Jonathan Hope, who was hailed as 'one of the most distinguished organists of his generation' by the German Eifel-(Moselle) Zeitung. Formerly organ scholar of Southwark and Winchester Cathedrals, Hope is currently Assistant Director of Music to Adrian Partington in Gloucester: hence he is the organist on the original SOMM recording of Venables' Requiem, SOMMCD 0618), and is well used to playing alongside orchestras, on both this occasion and on several CDs.

It is here that the disturbing tramp of the 'Dies Irae' passage, offset by a particularly well-employed bass solo, raises fearsome doubts. Yet in this movement come touching details, most especially the viola, then the oboe, peering enticingly through the textures, the latter as plaintive as (perhaps it was) a cor anglais. Gripping, personal, yet also universal. Where there are modulations, for instance to B major, one is reminded not for the first time of Dvořák.

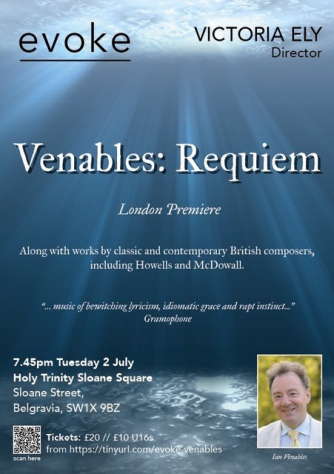

It is perhaps not surprising that Adrian Partington, who launched the Requiem in a live performance with his choir of Gloucester Cathedral, comments that Ian Venables' setting is 'eloquent, resourceful and exerts a strong emotional appeal'. That word 'resourceful' is particularly relevant. It is not just the quality of the melodic material perhaps that stands out, but the way Venable amplifies upon it, diversifies it, explores it, creating a marvellous web of beautiful sounds. To call the result 'masterly' would be no overstatement. Following its first appearance it was performed, again with organ, by the chamber choir 'Evoke', at Holy Trinity church in London's Belgravia, prior to Gloucester's Somm recording.

Poster for the first London performance

of Ian Venables' Requiem

Thus Ian Venables' Requiem is a journey, a spiritual journey, which expresses every movement that he sets with profound sensitivity and wonderful articulacy. It moves, inspires, at times frightens, often soothes, and by its close has achieved that feeling of relief and consolation, hope and optimism which he has set out to evoke. The Requiem is not just an achievement, though it is that. But it is - exactly - a masterpiece. Cathedrals not just in Britain, but across the world - and likewise choral societies - may be deeply grateful to have it to add, in the organ or the orchestral version, to their most intensely and sincerely felt religious repertoire.

Copyright © 10 July 2023

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK