- Palestinian

- Borodin

- Chandos Records Ltd

- Sarah Connolly

- Antonio Bibalo

- Donald Cameron

- Kazán

- Alexander Shelley

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Music and the Visual World, including contributions from Celia Craig, Halida Dinova and Yekaterina Lebedeva.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Music and the Visual World, including contributions from Celia Craig, Halida Dinova and Yekaterina Lebedeva.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

A spot of circumnavigation

on a Sunday afternoon

That's right, for today's dispatch I have chosen five pieces by five composers from five countries which are to be found in five different regions of our planet. None of the chosen composers have as yet been featured here, nor have any of the countries been represented up til now. I would love to include music from Antarctica but I have nothing to offer, not even a choral symphony of intrepid emperor penguins wintering out in unimaginable polar hardship.

In my very first piece here I talked about how music and composers - and by extension all fields of creative endeavour – tend to be sidelined or completely ignored in the wider world if they happen not to be from 'great' nations. This phenomenon was brought home to me again while flicking through The Penguin Modern Classics Book published in 2021. In this tome no less than one hundred and forty pages are dedicated to literature from Britain whilst a single collection of short stories is seen fit to represent a century or more of literature from the Netherlands.

You may say that this is only to be expected as Penguin is an English-language, British-based publisher and your point would be valid, but valid to the extent of granting Canadian modern literature two pages and that of the USA one hundred and fifty? Or as for the expected emphasis on literature written in English, does that justify France being represented by thirty-seven pages and Turkey by two books? The author to be fair does draw attention to the disproportionate nature of these figures and I understand that Penguin does not have the rights to publish every author or text they might wish to but the disproportion stands. Were this disproportion an accurate reflection of literary merit I wouldn't argue the point but frankly I think it is wildly inaccurate.

The author hints at this when he cites the anecdote of a Penguin editor who was berated by a Polish publisher for the fact that Czeslaw Miłosz's essays were virtually non-existent in Britain and when the editor actually read some he was suitably amazed. Had Miłosz been Russian or German they probably would have been given the full George Orwell treatment.

The same scenario is all too evident in the sphere of music. Basically it comes down to the fact that the 'winners' in history have a lot more resources – however begotten – to fight their corner. The only resources I have are my words. By these meagre means I will continue to fight the corner of great music and musicians who have been left out of the grand narrative of twentieth century music to anyone who cares to read.

1: Willem Kersters (1929-1998):

Symphony No 3, Opus 39 (1967)

Willem Kersters

Ceci n'est pas une pipe. It is a composer and a Belgian one at that, born the same year his compatriot René Magritte produced his famous/infamous La Trahison des Images. Unlike Magritte however Willem Kersters was Flemish; a child of the great city of Antwerp.

The third of his five symphonies serves as well as anything as an introduction to what he was about as a composer. The first movement is built upon a five note theme which is blasted out by the brass in a foreboding manner right at the outset. It becomes very quickly evident that apart from some rare moments of reflection this movement knows exactly where it is going and seems in a hurry to get there. Its unstoppable momentum is quite thrilling. Indeed its propulsive energy threatens to tip over at times like a bull in a china shop.

The symphony as a whole makes very intriguing use of a piano not as a concertante instrument but simply as another orchestral sonority and resource. The central movement is a very different affair. It is a world of shadowy unease that has Bartók's night music in its genes.

The final movement seems to want to indulge in more orchestral rough and tumble but after a few minutes of thrusting dynamism and maybe due to the exertions of the first movement it seems almost spent. Gradually the atmosphere of the middle movement seems to penetrate and mingle with the texture of the first as a synthesis of opposites. The driving energy manages to muster up one last enormous climax that spills over into music dressed only in harp and woodwinds that finally and mysteriously drifts off into who knows where.

This symphony was released on LP in a more than decent recording exactly half a century ago. I may be wrong but I don't believe it has been recorded since or that anyone has taken the trouble to put that recording on CD.

2: Gustavo Becerra-Schmidt (1925-2010):

Symphony No 2 (1957)

From Antwerp we descend all the way to thirty eight degrees south of the equator to the city of Temuco in Chile where Gustavo Becerra-Schmidt was born. When Pinochet and the military seized power in 1973 he went into exile in West Germany. I don't know if it is by design or pure chance but the soundworld of this symphony has something in common with the music of another composer who sought refuge in exile from another dictatorship; namely Roberto Gerhard who moved to England to escape Franco's ajuste de cuentas after the Spanish Civil War. It is a short symphony in three movements all of which have Biblical subtitles. The central movement especially is quite magical due in no small part to its touches of tuned percussion and the final movement finds an unexpected and effective - but not gratuitous - place for the use of a theremin or some similar instrument. All in all a very impressive work which makes one want to hear more of this composer.

L Schidlowsky: Triptico; G Becerra: Sinfonia No 2; C Garrido-Lecca: Sinfonia en 3 partes. Orq Sinf de Chile / Victor Tevah. © LMX

The three works on this LP were prize winners in a contest organised or at least sponsored by a sugar refinery of all things. Interestingly the Becerra-Schmidt was only deemed worthy of the second prize behind the work by Leon Schidlowsky. I don't agree with that judgement but Schidlowsky, who only passed away last year, is another composer worth investigating, if you can find anything.

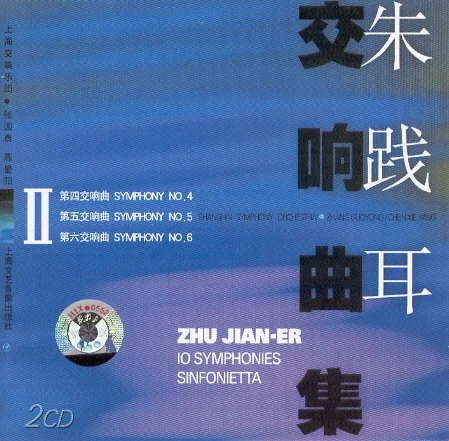

3: Zhu Jian Er (1922-2017):

Symphony No 6, Opus 35 (1994)

Zhu Jian-Er: 10 Symphonies; Sinfonietta

Zhu Jian Er is the only Chinese composer who I have as yet heard who has successfully managed to marriage broadly European classical music and his own enormously rich heritage of music. Too many of these attempts by other composers tend to be woeful concoctions that amount to little more than second rate Tchaikovsky or Strauss with some traditional instruments added on for some supposedly authentic local colour. Zhu Jian Er's works inhabit both traditions but are more than the sum of their parts. The fusion is one made at the very deepest level of conception, feeling, structure and execution and not another awfully anodyne cut and paste crossover.

He received his education in Western classical music in the Soviet Union and it is noticeable in his first symphony which took him the best part of a decade to write but in all his subsequent symphonic adventures his music became more and more individual, idiosyncratic and intriguing. This symphony is a perfect example. In his wish to use Tibetan music as part of the symphony's texture he had the novel and wonderful idea of fusing the orchestra with tapes of his own various and enormously rich field recordings from Tibet. The result is something quite spellbinding and a very poignant and eloquent expression of and commentary on the troubled history between Tibet and China.

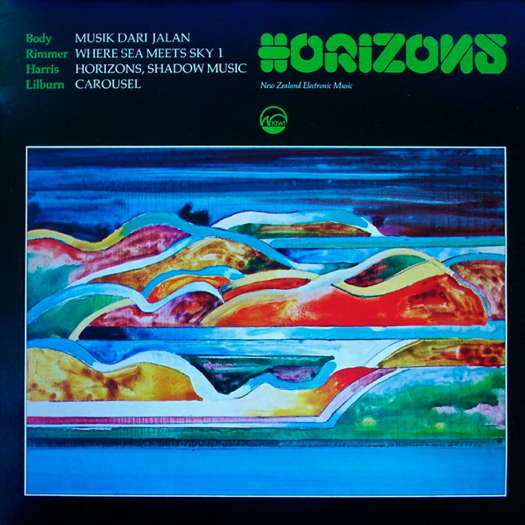

4: Douglas Lilburn (1915-2001):

Carousel (1976)

Horizons: New Zealand Electronic Music. © 1977 Kiwi Pacific Records Ltd

As a composer Douglas Lilburn in a sense lived two lives. The first of these saw him produce many very fine compositions for traditional forces, if too indebted to Sibelius for their own good. His second life, or rebirth if you will, was caused by his discovery of and hard won battle with the potential of electronic music of which he was a true pioneer. Lilburn was a son of one of the most singular places on earth: New Zealand / Aotearoa. A singularity doubtless helped by its enormous good fortune in avoiding human occupation for longer than anywhere else.

Just as Sibelius had wanted to express his natural surroundings and the inspiration they gave him in his music, Lilburn wanted to do the same. Being from a land of so much unique, indeed endemic, flora and fauna, Lilburn realised that electonic music was the revelation he had been waiting for; the means by which he could fully do justice to his 'heritage of timeless natural sounds'. As we are on a global merry-go-round this week I have chosen his piece Carousel as a fine example of what he was able to create in this new terra australis of sound.

5: Priaulx Rainier (1903-86):

Aequora Lunae (1967)

Priaulx Rainier

If I say that this is a major piece for orchestra that I have never heard and has never been recorded, by a composer whom I rate very highly, and that among its seven sections - all inspired by the seas of the moon - there are to be found titles such as Sea of Rain, Sea of Clouds and Lake of Dreams, I hope it won't come as a surprise to anyone that it more than deserves this week's nominaton for inclusion among those Keatsian unheard melodies to which last week's column was dedicated. Priaulx Rainier had a lot in common with Douglas Lilburn in that the natural sounds of her native South Africa in which her childhood and adolescence were bathed left an indelible impression on her and served as a unique repository of sonic souvenirs from which she could reap throughout her composing career.

As I sit here writing this, it is literally infuriating to think that this major piece has never been recorded when so much fluff and porridge receives multiple recordings. Maybe to hear it I shall have to go to the moon or wait until our beloved satellite actually has seas, oceans and lakes of its own. When I get there maybe I shall do a spot of circumnavigation of our Solar System but for now I think we have had enough travelling for one day. Time for a lie down.

Copyright © 9 April 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain