- de Falla

- Henri Meilhac

- Marcel Tournier

- Sverre Valen

- Larry Sitsky

- Hans Werner Henze

- Charles Hoffer

- Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Last Gasp of Boyhood. Roderic Dunnett investigates Jubilee Opera's A Time There Was for the Benjamin Britten centenary.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Last Gasp of Boyhood. Roderic Dunnett investigates Jubilee Opera's A Time There Was for the Benjamin Britten centenary.

All sponsored features >>

Rough winds do shake

May has barely begun and already the mercury is touching points in the thermometer which impede the normal workings of my mind. So although I know how I started the selection process for this week I got lost in a sweaty haze somewhere in the middle and have absolutely no idea how I came to the end. The thrust of the selection is based around this time of year; shamefully banal I know but as the days get hotter and the brain starts to simmer in its own soup I will struggle to come up with anything more inspired. Forewarned is forearmed. Five is even better.

1: Nikolai Tcherepnin (1873-1945):

The Descent of the Virgin Mary to Hell (1934)

Similar to the serpent's seasonal shedding of its skin I managed with quite a struggle to shuffle off my Christian beliefs in the late spring of my adolescence but my strict Catholic education left indelible marks. For that reason I still remember that May is Marian month: dedicated to the Virgin Mary. We spent a lot of time in the company of the Blessed Virgin back in those wildly innocent days but I was never introduced to this strange and shocking episode.

It is not surprising that it was a Russian composer who used this tale as the basis for a choral masterpiece as it seems to be something whose provenance comes more from the Greek Orthodox world. Although in the middle ages you can find references in the west to Mary as imperatrix inferni the influence seems clearly to have come from the east, which is not surprising as Christianity in its origins is an obviously Oriental faith.

Nikolai Tcherepnin

The purely Greek associations of this story are what are most fascinating to me, as the idea of Mary descending to hell to plead on behalf of suffering sinners has clear overtones of Orpheus' attempt to rescue Euridice from Hades. This profoundly Greek (mythological and philosophical) heritage of Christianity is something that is overlooked or downplayed these days. It is likewise brought home when you consider that so many of the early and extremely divisive debates in the Christian church about the true nature of Christ and other themes very often boiled down to arguments rooted in Platonic and Aristotelian physics and metaphysics.

Leaving all that to one side what Nikolai Tcherepnin – by pure fortuity a child of May - composed based on this tale is simply breathtaking. An absolutely extraordinary piece for chorus and orchestra which even more extraordinarily seems never to have been recorded. Obviously its subject matter meant it was untouchable during Soviet times but the fact that it hasn't been recorded since is extremely disappointing. Maybe I shall have to go down myself and beg for a recording but in the meantime I urge you all to enjoy this heavenly music.

2: Josip Štolcer-Slavenski (1896-1955):

Religiophonia (1934)

Josip Slavenski: Simfonija orijento. © 1974 PGP RTB

I began my mission here last August in Belgrade and it is to the Serbian capital I return now as it was there in the same year that Tcherepnin composed his oratorio above that Croatian born, Hungarian and Czech trained epitome of a maverick Josip Slavenski finished composing one of the most singularly extraordinary sui generis pieces I have ever heard.

This marvel is also called Oriental Symphony and five of its seven movements are dedicated to portraying various world religions. If that weren't fascinating and spellbinding enough each movement is in turn an exploration of a strictly compositional aspect of music starting from rhythm and working its way respectively through timbre, structure, melody, articulation, polyphony and harmony. Just when you think your jaw can't drop any further the floor gives way from under you and leaves you floating on a globally inspired but Yugoslav made magic carpet. Enjoy the ride.

3: Frederick May (1911-85):

String Quartet (1936)

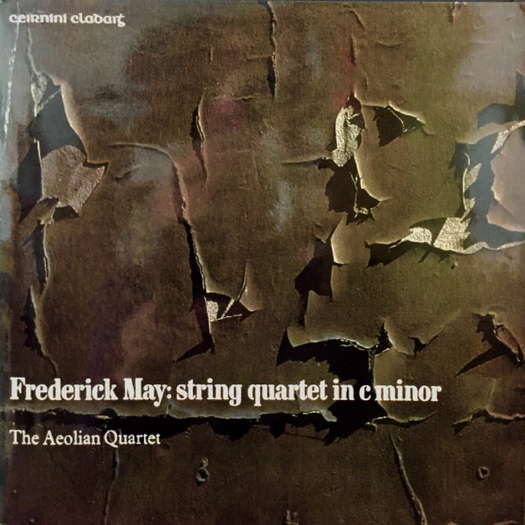

Frederick May: String Quartet in C minor. The Aeolian Quartet.

© 1974 Claddagh Records

One of the first, maybe the very first, orchestral concerts I attended in Dublin's National Concert Hall opened with a piece called Spring Nocturne by a composer called Frederick May. Both piece and composer were completely new to me at the time but I was intrigued enough to want to find out more especially when I discovered that Fred was a fellow Dubliner.

Based on Fred's life I could write a long essay about the realities of existence in modern Ireland since the dawn of the Irish Free State a century and one year ago but I don't have the space nor would it be appropriate here. Sticking solely to music this string quartet, his only one, is simply one of the greatest things ever composed by an Irish composer. One of the reasons for that is that if you hadn't been told beforehand you would have no reason to suspect that it had been written by an Irish composer. May's lack of insularity or provincialism was one of his greatest traits, not that he was ever thanked for it.

How this piece came to be recorded by Claddagh Records back in the early seventies is another story in itself but I will finish this piece with one more personal anecdote. One day on my lunchbreak while I was hurriedly looking through second hand records I came across this LP. My copy came replete with Irish Times newspaper cuttings mostly reviews of and commentary on the LP from when it had been first released. However one was dedicated to the then contemporary Dublin-Monaghan bombings which my mother, five-months pregnant with me at the time, mercifully managed to avoid. Some pieces of music seem to just have a way of seeking you out and of reminding you that music is never just music.

4: Åke Hermanson (1923-96):

Stadier, Opus 5 (1961)

Much like his peer and Norwegian neighbour Finn Mortensen, Swedish composer Åke Hermanson composed little but everything he did compose is of the finest lapidary quality. When you add to this fact that of his roughly thirty published compositions only a couple were written for a solo voice, it makes this song cycle stand out all the more among his collection of exquisite and rare jewels.

It sets words by his compatriot Karl Vennberg from his 1955 collection Vid det röda trädet. The soprano voice is accompanied by a mere four musicians which Hermanson manages to make sound like a small orchestra. Being as helpless when presented with a Swedish text as I would be in front of the extraordinary Gothic Codex Argenteus on display in Uppsala University I have maddeningly but fruitlessly tried to find a translation for these words.

Not to fear, Hermanson's extraordinarily evocative music more than suffices to create its own world. I have toyed with how to describe this piece and I will limit myself to saying it lies somewhere between Pierrot Lunaire and Crumb's Ancient Voices of Children but this is all Hermanson and Hermanson was a one-off, so just listen to it. Finally to would-be sleeve designers, look long upon this LP cover and learn.

Maros Ensemblen - Maros, Hermanson, Sandström, Sveinsson, Hambraeus.

© 1980 Caprice Records

5: Tera de Marez Oyens (1932-96):

Contrafactus (1981)

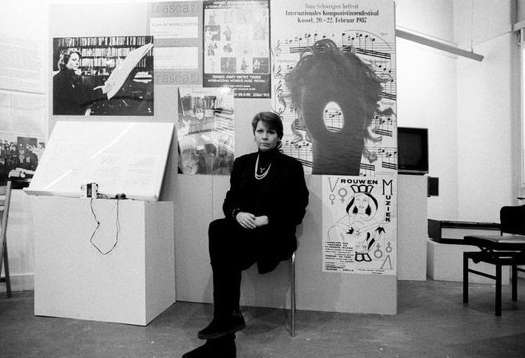

Until I heard this brilliant string quartet the music of Dutch composer Tera de Marez Oyens (born Woltera Wansink) was a closed book to me. After I had listened to it and furthermore read her saying in an interview that 'I have to compose every day, otherwise I feel sick' the decision about whether or not to grant her honorary status by the Oblivionopolis jury was a closed case.

Tera de Marez Oyens

Another thing she said in that straight-talking interview was 'the funny thing is when I compose I really compose kind of intuitively. It comes really from the heart. Then when a piece is performed and people say, "It was nice, but it was so intellectual", I am so surprised.' The but in that last sentence is very revealing.

Many people seem to have an issue with the idea of the intellect playing a vital role in music and this for me comes down to the broader issue of general musical education; an area in which, as in many others, Marez Oyens was a mould breaker. In her ideas about and practice of musical education for children she was adamant that children need to be exposed to contemporary music. This for me has always been a given and for the life of me I have never understood why children are not exposed to the music of Xenakis and Kurtág for example at the same time they are exposed to that of Bach or Mozart.

I know my own life could have been radically different if I had been lucky enough to enjoy such exposure. I still vividly recall how excited I was at the end of one music class when our teacher told us that next week we would be studying modern music. My excitement was matched, crushed and brutally surpassed by total dejection when at the appointed hour our teacher revealed to us that his idea of modern music was Tchaikovsky.

These ideas loosely tie in with some points touched upon by Béla Hartmann in his recently published wide-ranging article Quality or Taste? in which he states that 'you wouldn't judge a pop song by the same criteria as a symphony'. I would turn this around and ask, if you know very little about the nuts and bolts of music because your public education system taught you next to nothing about it, how can you possibly judge a symphony or any other form of music by any criteria other than those of a pop song? What other criteria are there for most people?

This is often brought home to me when I read 'critics' talking about Bruckner or Shostakovich symphonies in ways that remind me of old album reviews in Melody Maker or the NME. Music is a language and like every language, including your mother tongue, it needs time to learn and appreciate beyond the most paltry level. There will always be some people who have extraordinary seemingly innate musical abilities and others who due to their own personal passion will teach themselves about music beyond the basics but these are the exceptions that make the rule. For the vast majority music is a language, through no fault of their own, they don't understand.

When I tell anyone that music is a language, like any other, that needs to be learnt they almost always automatically label me an elitist which I just don't understand and more importantly feel does an enormous injustice to all those who have put the time and effort into learning music. Obviously music can bring immense enjoyment without much knowledge, pop music is the proof of this but when it comes to the full wavelength of music pop music – and I say this as a lifelong lover of pop music - barely constitutes one of the seven radiant colours of music's rainbow, never mind all the other non-visible wavelengths at either end of the visible spectrum.

Nobody considers as elitist the notion that in order to understand, appreciate or give remotely relevant opinions about German literature for example you need to study and learn German to basically a proficient level, this is just seen a plain good old common sense. So why is music not viewed in the same way? Why is it given special privileges? Apart from the fact that people have a lot of sentimentality wrapped up in music I can't see any valid reason for this.

As regards the relevance of classical music in modern society in which it has to compete with an extraordinary and ever-increasing variety of other distractions for people's attention, distractions that didn't exist in centuries gone by, there are no gimmick solutions. Simply put, until every teenager leaves school with the ability to play an instrument to a high level, is able to read scores with the same ease with which they are able to read books in their own language and has a very good grounding in and grasp of musical history - a musical history that doesn't rapidly jump over the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, doesn't simply wallow in the clichéd greatness of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven and pay no more than mere superficial lip service to the most diverse, complex, radical and richest epoch of musical history: the twentieth century; until this happens I think we are kidding ourselves about the future - or maybe it's already the present reality - of classical music in any real sense.

By that I mean classical music as a living, breathing, kicking and screaming conscience and passion at the pulsing enamoured heart of who we are as a society and not merely something you dress up for and pay a lot to enjoy in a public venue as another way of smugly confirming and demonstrating your all-important place in the social hierarchy. That's not music, that's a museum.

Copyright © 7 May 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain