SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Most Remarkable - Jamaican pianist Orrett Rhoden, heard by Bill Newman.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Most Remarkable - Jamaican pianist Orrett Rhoden, heard by Bill Newman.

All sponsored features >>

- Heli Lääts

- Alexandre Dumas

- Bulgaria

- Elin Manahan Thomas

- Samy Moussa

- Clara Wieck

- Denise Shepherd

- Dvořák: Violin Concerto

VIDEO PODCAST: Slava Ukraini! - recorded on the day Europe woke up to the news that Vladimir Putin's Russian forces had invaded Ukraine. Also features Caitríona O'Leary and Eric Fraad discussing their new film Island of Saints, and pays tribute to Joseph Horovitz, Malcolm Troup and Maria Nockin.

VIDEO PODCAST: Slava Ukraini! - recorded on the day Europe woke up to the news that Vladimir Putin's Russian forces had invaded Ukraine. Also features Caitríona O'Leary and Eric Fraad discussing their new film Island of Saints, and pays tribute to Joseph Horovitz, Malcolm Troup and Maria Nockin.

Last Gasp of Boyhood

RODERIC DUNNETT investigates Jubilee Opera's 'A Time There Was' for the Benjamin Britten centenary

For a quarter of a century Jubilee Opera has been lifting the standards of children's opera in Britain to standards that match anything in Europe.

It hoisted its flag to the mast with Britten -- The Little Sweep was its first production twenty-five years ago in 1988 -- and perhaps not surprisingly, given that it performs in the very building where Britten's operas began -- the Jubilee Hall, opened in 1887, where Albert Herring and later A Midsummer Night's Dream and indeed The Little Sweep had their world premieres.

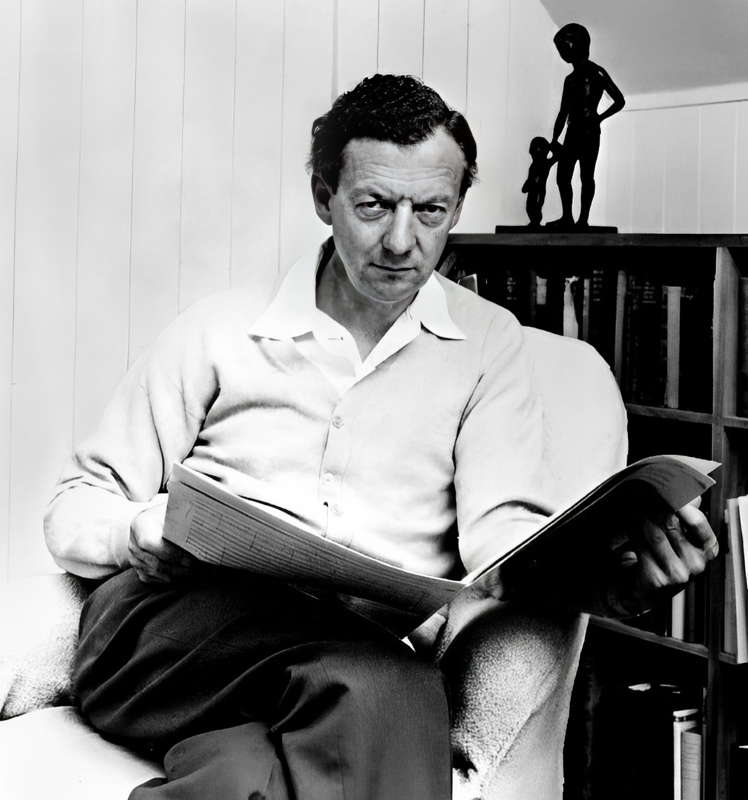

Benjamin Britten in 1968

But Britten's children's operas, vaudevilles, oratorios (Noyes Fludde, The Golden Vanity or St Nicolas) square with the company's aspirations, so he, though not he alone, plays a big part in their undertakings. It is appropriate and exciting that the company's often scintillating present artistic director, Frederic Wake-Walker, with one of Britten's closest and most inspiring allies and amanuenses, the conductor Steuart Bedford, have opted this year to look at Britten anew.

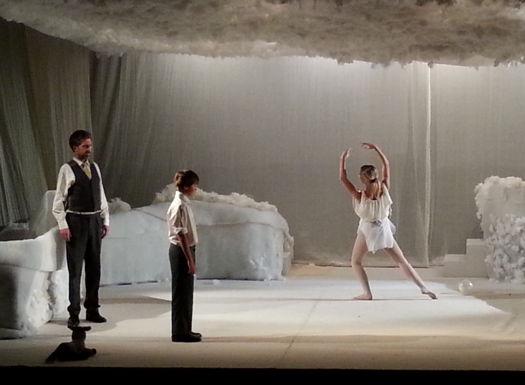

Jubilee Opera's director, Frederic Wake-Walker.

Photo © Conoclas-The Opera Group

The result: a wholly new stage piece, entitled A Time There Was (Britten wrote his Suite on British Folk Tunes of that name near the end of his life), which brings a wholly new perspective to Britten and his sometimes misconstrued take on youth [seen 10 November 2013, Aldeburgh, UK].

It might not unfairly be dubbed Britten and his Boys, along the lines of John Bridcut's film and book Britten's Children; but only on the understanding that it seeks to probe -- in many respects successfully, sometimes more incipiently -- how Britten (the Man, sung and played with wonderful, moving honesty and loyalty by the tenor Alan Oke), with his nostalgia for boyhood, might engage with the view of childhood and emerging youth he forged, idealised and occasionally parodied throughout his composing career. With Tom Stoppard and Alan Bennett stepping out to present Britten the man onstage, it stands in a noble line of new Britten stageworks.

All the music (a few bridge passages in style apart) is Britten; but Oke is 'The Man': any man looking back on childhood, his own especially, and coming to terms with the cruelty of life that sloughs boyhood off, wrenching, even raping, the boy away from his protected past and forcing him via adolescence -- maybe joyous, maybe pained, most likely both -- into adulthood.

As Wake-Walker puts it, 'Why do we cry when man is dead and gone / While no-one weeps as youth drops its petals one by one?' Quote? Self-quote? Half-quote? But one of the wonders of this show was that we did see the petals fall: not literally, in a politically incorrect, risqué self-unclothing; but emotionally, these boys ripped you apart -- Alfie Evans as the self-questioning boy (Miles' here painfully agonised, wonderfully sung malo ditty, 'than a naughty boy/In adversity', with cor anglais and harp); and Lucas Evans, who has one of the loveliest mezzo-like intonations I have ever heard from a Miles, as the extraordinarily mind-made-up Miles (The Boy) at the close.

'Miles, speak to me'. Alexandra Hutton as the Governess

and Lucas Evans as the boy (Miles)

Our supposed, almost ritual fear in the opera is that Quint, hero or villain, is trying to make Lucas' Miles almost pathologically bad: a view painfully naïve and simplistic. Perhaps the boy is using Quint to fill, like Heineken, those parts other beers won't reach. To give him an inkling of sexuality, a whiff of mild dishonesty, to make him a man; as his absentee Guardian, locking him in with a trio of females, so effetely declines to do?

So much of this, and more, we grasped here. Wake-Walker concentrated even more, in the final scene, on the Man: it is not Miles who is lost, torn: he -- in Jungian terms -- individuates himself, and uses the crushing joint pressure of the Governess and Peter Quint to catapult out and leap free.

Thus the most dramatic moment of the whole 'opera' or stagework is a kind of gainsaying of Henry James and Britten and Myfanwy Piper's death-laden Miles. Lucas Evans -- the boy -- outlasts the moment. Almost laughingly, certainly with new virile determination, he wrenches himself away from the conflicting adult 'brakes' upon him, different attempts to gag him, and instead joins the adult world.

There's no real reason why a staging of The Turn of the Screw itself shouldn't risk this trompe d'expectation; but it would require astonishing courage, and probably a writ from the composer's estate.

Jubilee's young performers are the tops. I could list ten or twelve who really stood out, just as even more made their mark with the brilliantly varied characterisations of Hans Krása's Brundibár, the opera composed for the children of (Mozart's) Emperor Joseph II's fortress of Theresienstadt, later the Nazis' Terezín holding camp in north Czechoslovakia, which provides such a wealth of characters for children to play. These young performers have character in buckets, and in places, if not throughout, the present show, they revelled.

Sammy (the Little Sweep) gets a hot bath

One could mention the brief snatch from Albert Herring (which is where we started), where the three kids -- Emmie, Cis and Harry -- make their nauseating voices available to teacher Miss Wordsworth (Alexandra Hutton ably took all the maternal roles) for the bellowed formal greeting to Lady Billows; or the nice little visual sequence from their The Little Sweep where little eight-year-old Sam gets a bath from Dickensian well-wishing ladies; there was a flood of parental and young birds -- Chaffinches, learned and bespectactled Owls, Turtle Doves and exquisite Herons, to preface the Dancers (Elizabeth Hawes and Bethany Rumbelow), who reflected the Raven and the Dove returning to Noye (Noah -- admirable baritone Alex Ashworth) to indicate growing hope of land ahead.

Noye's Fludde: Alex Ashworth (Noye) and the boy are given hope by the Dove

The winged dancers had the Blakean titles Experience and Innocence. Given that the dances (no choreographer credited), and a mite dull, needed greater relevance. Not so 'Come, come now a roundel and a fairy song', Titania's introduction to the fairies' 'You spotted snakes...' from Act II of Shakespeare's Dream, quite wonderfully sung by eight of the older boys. I agreed with some others I spoke to that the programme could have been more helpful about what music came from where; some even suggested the words might have been printed.

But I could understand the perpetrators' wish, a little earnest, to unify the work by not specifically associating each movement with a different opera. Here, the boys' willingness to emit lines like 'Some to kill cankers in the musk-rose buds, / Some war with rere-mice for their leathern wings, / To make my small elves coats ...' just confirmed that Jubilee Opera are complete pros. Once they were hunting for boys; now they are spoilt for young choice. Their kettles are singing.

'Hip, Hip, Horatio!' - The Battle of Trafalgar, in the Trafalgar Tavern

Thanks to The Golden Vanity and Jubilee's recent experience with staging Michael Hurd's Hip! Hip! Horatio -- undoubtedly one of their best stagings ever, so they should perhaps try another Hurd in due course -- the naval bits were rather a hit. You got the impression the Turks (Captain: the vocally and visually rather good Julian Edwards) were just as honourable and reputable as the slightly gung-ho Brits (skippered by Theo Bimson), so a modern message there perhaps. Elements of the Crew's jiggling and huzzaing might have been more tightly focused: up to sixteen sailors were cavorting at one time or another. There were also waves -- perhaps for Noye as much as here -- which is the sort of thing Jubilee usually pulls off rather well.

Oke -- who went straight back to sing Aschenbach in Death in Venice for Opera North, where he was a long established regular even when still singing baritone -- is undoubtedly the main figure in the drama, and his pairing with Steuart Bedford's often glittering orchestra always drew you in: a seriousness, a generosity, a searching and reaching out, as in Britten's song-cycles, or indeed the Nocturne, from which we heard a moving extract, 'Encinctur'd with a twine of leaves ...'. which proved a highlight of the entire evening.

But one of the other magical moments came from young (sixteen, turning seventeen-year-old) alto Jamie Rose, who with fairies in attendance (their little ditty actually echoes the riveting tuned tympanum of the opera's opening) sang 'Meet me all by break of day'. We all know the Alfred Deller version, and many, starting with James Bowman, that have come since. This was up with the best of them. If the voice needs some training, the confidence boosting, the tone doesn't: it is all there. This could be a countertenor of significance and standing.

Jamie is elder brother of the company scamp, a singing star and a serious-minded actor of endless spirit and flair -- Will Rose is now ready for a really big acting challenge -- whose antics I usually have to applaud, and who celebrated his fourteenth birthday amid hilarity on the day of the last performance.

'Hail Mortal, Hail!' A puzzled Bottom (Alex Ashworth) is accosted by four fairies. Alfie Evans, one of the highly impressive boy Mileses, is fourth from right.

But this time it was those two Boy / Mileses, (the unrelated) Alfie and Lucas Evans, for whom I have to save the praise. Even the wee chappie (William Gidney) who played Miles qua kiddy ('Tom, Tom the Piper's son', chirrups Myfanwy Piper's libretto, perhaps with a whisper of irony) did rather well. Alfie (he even sounds like a character out of Herring) is poignant, his tragic delivery was not betterable: this Malo ached; you could see little hints of misbehaviour in his body language: he seemed to feel guilty just to be a boy.

Upright, though seeming younger, Lucas Evans had no such guilt, but a flagrant terror. Of what? We saw as Wake-Walker's, and Oke's, and Bedford's, joint climax approached. This was not a boy about to be squeezed to death in a ghastly embrace, but a chrysalis about to explode. And the unuttered line? Something like 'A plague on both your houses'.

'We have destroyed him'. The boy - Miles (Lucas Evans) and Governess (Alexandra Hutton). Steuart Bedford (below) conducts.

Miles, formerly the Boy, has his coat and muffler on, as if freezing to death in the Ice Age atmosphere Shizuka Hariu has conjured up (not, let it be said, understated). But he is not preparing for the last gasp of his boyhood breath. Only the last gasp of boyhood. And with that, duly wrapped up, he is off, a new-found young man, to grasp the future.

One day, so we sense from Oke's choking regret, he will look back on this moment, and the loss of what precedes it, with profound sadness. He will wish that once again, he were in an apple tree, for the joy of being naughty. But right now, he's up for it. The world is his oyster. He's out to win.

Copyright © 1 December 2013

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK