- synth

- Giovanni Battista Bononcini

- Arabic music

- Paul Plishka

- anonymous

- Ihor Markevych

- Opera National de Paris

- Daniel Grossman

The home country grown strange

For as long as I can remember the harp has been my favourite instrument. Growing up in the country that has the harp as its national symbol, indeed the only country in the world that has any musical instrument as its national symbol, I suppose must be responsible, at least to some degree, for my long-standing love affair with this most magical of instruments.

For an instrument with such a long, vast, rich and global history, and one with an extraordinary range of sonic possibilities, people's typical expectations of harp music and harpists today seem sadly stereotypical. My selection for this week, and it wasn't at all easy, was born, in part, out of a desire to counter somewhat any typecasting from which the harp tends to suffer in the public imagination these days.

Whatever about the selection of this week's far from famous five, the whole inchoate idea in the first place was plucked out of the ether by the hardest working member of the research team here in Oblivionopolis. So if you don't like this week's offering you can blame both of us and not only me for once.

1: Éliane Radigue (born 1932):

Occam 1 (2011)

Éliane Radigue: Occam Ocean 1. © 2017 Shiiin

Éliane Radigue is a singular artist. Singular in her sound and singular in her dedication to that sound. For most of her life she created her own universe through the ARP 2500 modular synthesizer. She didn't start to compose for acoustic instruments basically until her seventies and she was almost eighty years old when she embarked upon her Occam adventure which at last count has now reached a staggering eighty-one compositions for a vast array of mostly chamber ensembles.

This piece is for solo harp but the score also calls for the strings to be played with bows. I remember when I was ten years old my teacher at the time: Mr Flaherty - probably the best teacher I ever had - talking to us about Occam's razor or the principle of parsimony. One shouldn't choose the simplest way or answer because it is the easiest but simply because and only when it is the best.

Mathematics and science since the fourteenth century when William of Ockham first posited this notion have proved this be true time and time again often to a breathtakingly beautiful extent. Straight off I think, among many examples, of Mendeleev's predictions based on missing pieces in his periodic table jigsaw for the properties of elements that didn't exist at the time and which nobody, except Mendeleev more or less, had any reason to presume ever would exist but time proved him right. Or James Clerk Maxwell's equations which proved that electricity and magnetism are basically two forms of the one reality. These equations contained a constant c which stands for the speed at which electromagnetic waves move. The value of c that came out of Maxwell's brilliant equations just happened to be to all intents and purposes exactly the same as the then known speed of light, proving, without even trying as it were, that light is a form of electromagnetic radiation.

Science and maths is one thing, history is another. As Diarmaid MacCulloch put it 'There is no surer basis for fanaticism than bad history, which is invariably history oversimplified.' The music of Éliane Radigue is not oversimplified. It is as simple as it needs to be in order to express what it wants to express the best way it can, something which, despite perceptions to the contrary, is far from simple to realise or execute: the art that conceals the art.

2: Roman Ledenev (1930-2019):

Six Pieces, Opus 16 (1966)

Soudobá Sovětská Hudba. © 2020 Supraphon

As with Jovdat Hajiyev whom we met in Champions of Oblivion Roman Ledenev's name exists in multiple formats due to the differing attempts at rendering Russian phonemes and Cyrillic letters in Latin script. For a composer whose music is already little known this state of affairs obviously only makes the bushel under which his light is securely hidden all the more overgrown and unfairly fecund. These tantalising short pieces are written for harp and string quartet but have none of the expected associations with French Impressionist music scored for the same forces. They leave one very eager to hear more music by this composer with or without harp. Let's hope something appears in Northern Flowers next harvest.

3. Giacinto Scelsi (1905-88):

Okanagon (1968)

Giacinto Scelsi: Yamaon; Anahit; I presagi; Tre pezzi; Okanagon.

Klangforum Wien / Hans Zender.

© 1999 Kairos Music Production

I honestly don't know so I am presuming that the title of this piece refers to the people indigenous to the Pacific border country of what is today the USA and Canada. Giacinto Scelsi calls it a rite so I imagine it is his idea of an animistic ritual. He goes on to say that it should be considered as the heartbeat of the Earth. If you bear in mind that the heart, or at least the centre, (its heart may be elsewhere or nowhere) of our planet is a big ball of iron at the same temperature as the surface of the sun I don't think you will be surprised to know that the sound of this piece is not exactly Ravel.

It is written for a trio of harp, double bass and tam-tam and requires amplification. Scelsi also asks that in performace, if possible, the musicians should be hidden from view. The harp is specially tuned for the piece and the strings are to be played with a metal plectrum. In the way that Leonhard Euler inaccurately but beautifully described the sun 'as a bell ringing out light' this piece can be heard as the Earth conceived as one great throbbing organism to whose simmering shimmering vibrations we are all susceptible whether sensed or not.

4: Arturo Márquez (born 1950):

Peiwoh (1984)

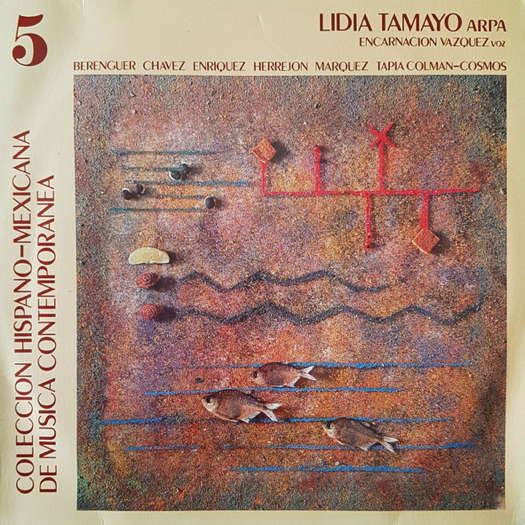

Coleccion Hispano-Mexicana de Musica Contemporanea 5.

Lidia Tamayo, arpa. © 1986 EMI

There are many women who play and have played the harp but the writer of the liner notes for this LP in his harping on about the perennial and synonymous, as he seems to see it, connection between women and the harp makes claims that don't stand up to even a cursory look at the facts or hide the sexist overtones. He tells us that 'As it was an intimate and dreamy instrument it was played almost exclusively by women'. Or 'It has always been a woman's instrument whether in the home, in palaces or in the orchestra and composers have accentuated its aptitude for tenderness and mystery assigning it especially to female musical expression.'

I don't know if tender is the appropriate adjective to describe Scelsi's Okanagon or what Carlos Salzedo would make of these quotes but more importantly he is clearly unaware of Gaelic culture in which the playing of the harp was very strictly a male preserve. The same applies for court music during the Spanish Renaissance in which the harp was played by men. But you don't have to cross the Atlantic to find men playing the harp. Much closer to the writer's home you will find that the Paraguayan harp is also traditionally played by men, indeed throughout Latin America to the best of my knowledge it is as common, if not more so, to find men as well as women playing the harp. Furthermore arguably the most famous harpist in the Spanish speaking world at the time these liner notes were written was Nicanor Zabaleta: yet another man.

This exquisite little piece by Mexican composer Arturo Márquez is based on a Taoist tale recounted by Japanese writer Okakura Kakuzō in his landmark The Book of Tea - a remarkable essay not only for the fact that he wrote it in English but also because it prefigures ideas made more famous by Edward Said by some seventy years. The writer of the liner notes tell us it is a 'marvellous tale' but I ask myself if he even read it as Peiwoh the protagonist of the tale and a harpist is - yes you've guessed it - once again a man, a prince no less. Peiwoh is the only one able to produce anything other than unspeakable ghastliness from the harp in question. The tale turns out to be a beautiful and profound reflection on artistic experience and appreciation as Peiwoh says he let the harp choose its theme and ultimately he didn't know which was Peiwoh and which was the harp so intimately united was the dancer and the dance as Kakuzō writes:

At the magic touch of the beautiful the secret chords of our being are awakened, we vibrate and thrill in response to its call. Mind speaks to mind. We listen to the unspoken, we gaze upon the unseen. The master calls forth notes we know not of. Memories long forgotten all come back to us with a new significance. Hopes stifled by fear, yearnings that we dare not recognise, stand forth in new glory. Our mind is the canvas on which the artists lay their colour; their pigments are our emotions; their chiaroscuro the light of joy, the shadow of sadness. The masterpiece is of ourselves, as we are of, the masterpiece.

The harpist on this recording however is indeed 'una dama' none less than the mighty Lidia Tamayo for whom this piece was written. To be a harpist it doesn't matter what's between your legs as long as it's a harp.

5: Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007):

Freude (2005)

Klang - 2 Stunde - Stockhausen. © 2006 Stockhausen-Verlag / Stockhausen 84

Karlheinz Stockhausen may not be a composer who comes to mind when you think of the harp but apart from the fact that I love this piece that's exactly why I have chosen to end with it today. It's part of his last great cycle of works Klang which he never managed to finish. Klang was envisioned as a cycle of twenty-four pieces in relation to the twenty-four hours of the day. Freude is the second of these pieces. It originally had a different title but its composition brought Stockhausen so much pleasure that he changed the title to its present form which means joy. It's for two harpists who are also required to sing. The two harps, two voices, four hands, four feet, twenty fingers and twenty four sections all combine to create one gloriously joyous experience and although the words sung are from the Christian hymn Veni, Creator Spiritus I prefer to hear Joyce's:

Woodshadows floated silently by through the morning peace from the stairhead seaward where he gazed. Inshore and farther out the mirror of water whitened, spurned by lightshod hurrying feet. White breast of the dim sea. The twining stresses, two by two. A hand plucking the harpstrings, merging their twining chords. Wavewhite wedded words shimmering on the dim tide.

Article copyright © 30 April 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain