- Rudolph Simonsen

- Witold Lutosławski

- Giovanni Battista Martini

- Sigrid Kehl

- Ray Steadman-Allen

- Scandinavian

- Yuan Shihai

- Graham Vick

Introduction

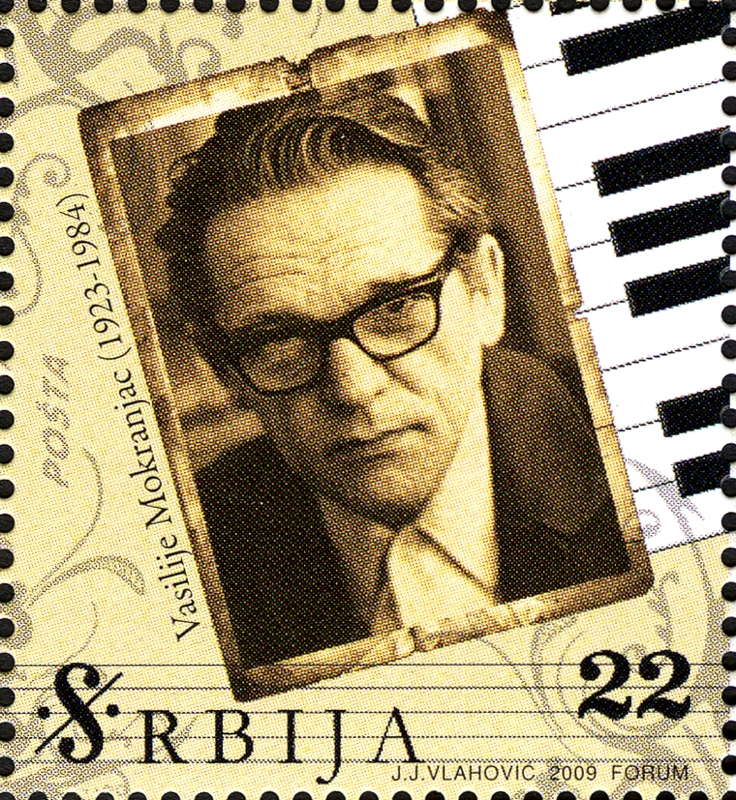

On a late spring day in 1984 a sixty-year-old man threw himself out of his apartment window upon the mercy of gravity and thus to the eternal void below. Who was he? He was a husband, a father and a professor of composition at his local Faculty of Music. He also happened to have written some of the most, by turns, powerful, passionate and poignant music one is ever likely to hear.

Listen — Vasilije Mokranjac: Symphony No 4 (1972) (2:23-3:21)

Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra / Živojin Zdravković :

His name was Vasilije Mokranjac. A name one will struggle, almost certainly in vain, to find within the pages of the numerous books - encyclopedias apart - written about the music of the twentieth century.

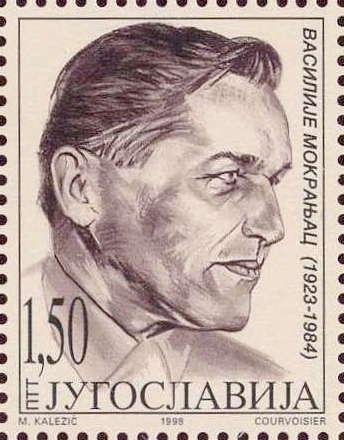

Serbian composer Vasilije Mokranjac (1923-1984), honoured on a 2009 Serbian stamp

This state of affairs is not unique to Mokranjac. He is one of dozens, possibly hundreds, of men and women who devoted their lives to the composition of extraordinary and extraordinarily worthwhile music throughout the course of the last century. A lifetime's worth of dedication and devotion oftentimes in the face of extreme and multiple difficulties which in many cases was ignored or treated with total indifference by their public and incomprehension, hostility and derision by many of their musical peers. Music in many instances never performed, recorded or even printed. The absence of so many of these singular souls from the pages of all those histories of twentieth century music, an absence mirrored in concert programmes and radio broadcasts, is the raison d'être of this series.

There are various reasons why this phenomenon exists and what remains of this introduction shall briefly examine some of them. Doubtless the principal reason is the vastness of the terrain encompassed. It is not by chance that The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians stretches to multiple volumes. Granted Grove tackles a much broader gamut than what follows endeavours to do, however, even if Grove limited itself to a comprehensive treatment of the music of the twentieth century; several tomes would undoubtedly be required to do the subject justice. With such a daunting amount of music and number of musicians, it is only logical and completely understandable that any treatment of the topic will necessarily have to resort to a stringent selection process.

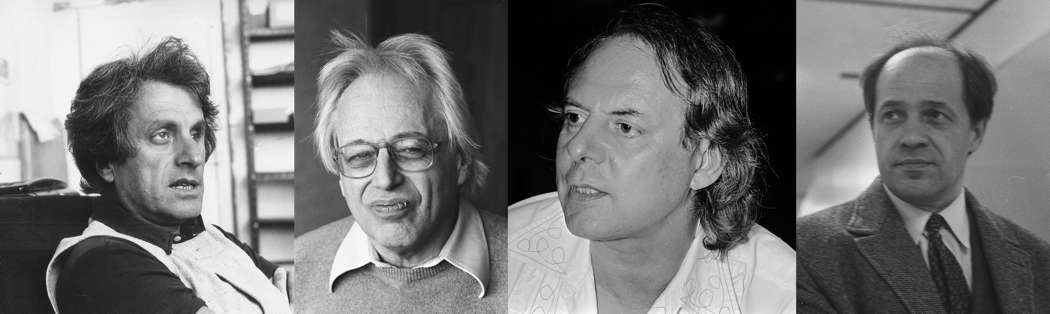

This being the case, it is only right and proper, especially when the story of twentieth century music is being told to a general audience, that the brightest stars of the last century's musical firmament who radiated the most intense and far-reaching light deserve their place at the front of the queue. Mokranjac, for example, was part of the same generation as Boulez, Stockhausen, Xenakis and Ligeti. However great his talent may have been, his degree of originality, his overall importance to and influence on the course and development of music in the twentieth century is much less than that of any member of that quartet of outstandingly powerful and visionary creative geniuses. As such, it only stands to reason that authors of histories of twentieth century music rarely, if ever, find a way to find a place for composers like Mokranjac in their grand narratives and thus their story remains untold.

Bright stars from the twentieth century musical firmament. From left to right: Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001), György Ligeti (1923-2006), Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007) and Pierre Boulez (1925-2016). Photo of Xenakis © Les Amis de Xenakis

Related to this is the fact that historians, and academics in general, look to find neat narratives in the stories they wish to tell. They find the abundant mass of information far easier to tame if they can slot individuals and their disparate tales into seemingly connected schools or groups. If they can find an overarching process of cause and effect, some kind of grand dialectic that can make what happened seem almost inevitable and destined. If they can show history as something settled and finished, as if everybody involved in the making of history was the possessor of a crystal ball; able clearly to foresee the consequences of their actions and decisions taken at any particular moment. However far from the truth this in fact may be, it at least makes for a comprehensible read. So in the case of the story of classical music in the twentieth century what does one do with composers who do not fit into this scheme of things? Composers who never belonged to any group? What is to be done with composers who, in a scenario where different choices about compositional methods or allegiances or not to certain traditions are presented almost like trench warfare, occupy a metaphorical no-mans-land? With those who were neither proselytisers for the avant-garde, nor arch-conservatives? How does one tell the story of those artists who do the most radical thing any artist can ever do; ie, avoid all the cultural warfare and sensationalist posing and quietly live their lives the best they can and go about doing what they were born to do; write music? The answer would seem to be to leave them and their music in the shadows, or leave it to someone else foolish enough to think they are up to the task of telling their story.

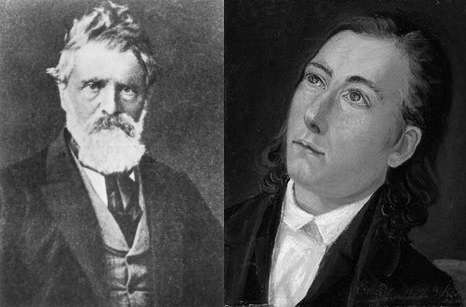

Another reason is the issue of provenance and pedigree. The Faculty of Music of which Mokranjac was professor is located in Belgrade. Today, the capital city of the sovereign Republic of Serbia. Which for most of his adult life and at the time of his untimely death was the capital of the Socialist Republic of Serbia. One of six such republics that made up the then Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Both Serbia today and Yugoslavia, when it existed, is and was considered as being strictly on the fringes, if not completely beyond the pale, of musical culture, by those who view themselves as denizens of its centre. This is an aspect of an unjust and unjustified way of thinking that seems to believe that great music can only come from 'great' centres. Music is not unique to this myopic mentality. An arrogant and erroneous mentality that would seem to be a hangover from imperialist times and ways of thinking. In order for artists born in what were, and clearly for many still are, conceived of as 'lesser' nations to attain some parity with their peers from the 'great' nations, the only chance would seem to be to move to one of the accepted artistic capitals. What would be the standing of Oscar Wilde today in the canon of English literature if he had never left home, or if Joyce, or Beckett, or Picasso or Brâncuşi had likewise never gone to Paris? One can argue about the relative greatness of Pessoa or Borges, but doubtless the arguments would be less necessary had they been German or Russian. Extraordinary painters like Peder Balke or Lars Hertevig might well be household names if only they had taken the trouble to be Italian or even Dutch but not Norwegian.

Norwegian painters Peder Balke (1804-1887) and Lars Hertevig (1830-1902)

This situation is, seemingly, only exacerbated for composers who lived out their lives behind the Iron Curtain. It would seem that any culture created under the auspices of the Soviet Union is severely tainted. Either because it tacitly or expressly supported the morally bankrupt regime under which it was produced, or because it was forced to observe the populist and hackneyed strictures of socialist realist dogma. It is judged as lacking all authenticity or artistic worth. Even the slightest exposure to the incredibly copious and varied recorded legacy of classical composition behind the Iron Curtain proves that this is a gross oversimplification and that the authenticity or not of something as nebulous as instrumental music is a far subtler subject than some would seem to think. To take a broad brush to the vast canvas of Eastern Europe and what were once socialist republics within the Soviet Union is simply short-sighted and superficial. There were many facets of life and experiences in common for citizens of the various countries throughout this territory during the Cold War but at the same time there was no absence of local idiosyncrasy. A situation which seems all the more obvious when one considers and contrasts the reality that the Iron Curtain and its nefarious influence lasted for less than half a century in a world that had known century upon century of multiple and varied ethnic, religious, linguistic and cultural diversity and intermingling.

Finally as a corollary there is the belief, by some, that all the great music worth hearing has by now long been discovered. If we have not heard it by now, that clearly means it is not worth hearing. This misguided notion does not take into account the enormous number of variables that go into making a cultural canon and just how arbitrary and relative these things can be. This phenomenon is even greater where music is considered as there are so many intermediaries between a composer and his or her audience: manuscript, copyist, publisher, promoter, musician(s), concert, venue, recording, record company et al. There is one further and important point which I have not mentioned above as I do not have the space to give it the treatment it deserves here and that is namely that for all the obstacles a composer like Mokranjac has to surmount in order to receive the recognition due to him, the problems are only multiplied and magnified for any composer who happens to be a woman.

Vasilije Mokranjac, pictured on a 1998 Yugoslavian stamp

Listen — Vasilije Mokranjac: Poem for piano and orchestra (1983)

Live 1986 recording from Spain (8:01-9:00)

Dušan Trbojević, piano; Symphony Orchestra of Belgrade RTV / Armando Kreiger :

What follows, soon, is not an attempt to rewrite the history of twentieth century music. It is simply a humble attempt to acknowledge, pay respects and give thanks to the many composers who are not to be found within the typical histories of twentieth century music for the various reasons that have been presented above. But who in their own way have left us with an extraordinary legacy of magical music that can bring untold riches to those with open ears and a curious disposition.

Copyright © 20 August 2022

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain

VASILIJE MOKRANJAC (1923-1984)

TWENTIETH CENTURY CLASSICAL MUSIC

CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT SERBIA

ARTICLES ABOUT WOMEN COMPOSERS

ECHOES OF OBLIVION - FURTHER INFORMATION