CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

- Bernstein: Chichester Psalms

- Rudolph Hermann Simonsen

- Wiener Philharmoniker

- William Schuman

- Gounod

- Hermann Mendel

- Puccini: Il trittico

- Richard Phillips

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Music and the Visual World, including contributions from Celia Craig, Halida Dinova and Yekaterina Lebedeva.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Music and the Visual World, including contributions from Celia Craig, Halida Dinova and Yekaterina Lebedeva.

Four by Four by Five fff

A fortnight ago I talked about the amazing journey of the symphony in the twentieth century. If anything, that adventure was even more extraordinary in the unique realm of the string quartet. Here, and unlike in the case of the symphony, there was, in principle, no composer who did not feel the irresistible pull of this purest and most exposed of musical forms. I think in the second half of the nineteenth century a lot of composers felt that Beethoven had said the last word when it came to the string quartet as he had with most forms he poured his genius into. It took another genius: Béla Bartók, among others, to show, in his utterly unique way, that far from being the last word on the matter, Beethoven's final quartets were just the jumping off point that opened up literally limitless possibilities of form and expressivity and of what a composer could actually do with two violins, a viola and a cello in an attempt to realise musical ideas. The legacy of the string quartet from the first decade of the twentieth century until today has been an extraordinary demonstration of this richness and it shows no signs of abating any time soon. The fact that in this form one can listen to a direct dialogue, in a way that is not possible to any similar extent anywhere else, between Schubert and Xenakis for example is just one of the many aspects that so fascinates, seduces and astounds about the string quartet.

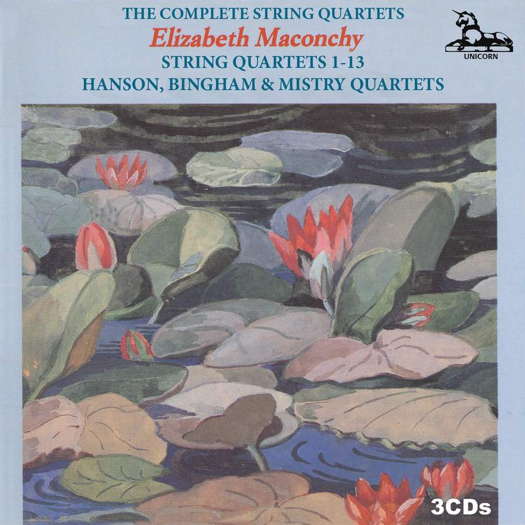

1: Elizabeth Maconchy (1907-94):

String Quartet No 10 (1971)

To better understand the attractions of the string quartet one can not do much better than taking it from the horse's mouth as it were. Here are some liner notes written by Irish composer and lifelong dedicatee of the string quartet, Elizabeth Maconchy, on the occasion of the first recording of her tenth quartet from a Canadian LP released fifty years ago:

It is the form which has seemed best suited to express the kind of music I want to write – an impassioned argument. Four players, like the characters in a drama, each pursue an independent line, yet react upon and influence each other. I find it the most exacting but the most satisfying medium to work in, with its need for economy, clarity and closely-knit form.

It is only fitting that this particular quartet owes a notable debt to Bartók's extraordinary sextet of quartets.

Elizabeth Maconchy: String Quartets 1-13. © Unicorn

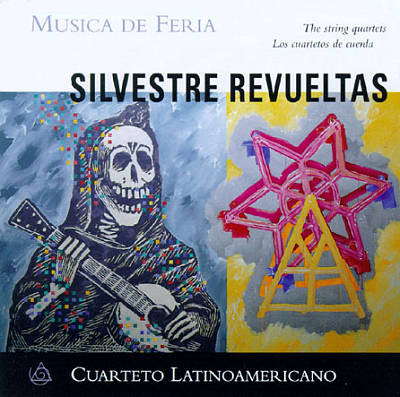

2: Silvestre Revueltas (1899-1940):

String Quartet No 4 (1932)

They say life begins at forty; tragically, for great Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas, that was exactly when it ended. His flamboyant orchestral scores are relatively well-known and often enough recorded, but that can definitely not be said for his scintillating string quartets, which for me are on another level as regards compositional brilliance and lasting musical worth. Unlike Sensemayá or La noche de los Mayas, his four quartets live permanently in a musical day of the dead and are rarely given a chance to live and breathe, either in live performance or commercial recordings. They were all written in a creative burst over two years. Sample the last and shortest of them if you haven't heard them before.

Silvestre Revueltas: The string quartets. Cuarteto Latinoamericano

3: Yuri Falik (1936-2009):

String Quartet No 5 (1978)

The first time I heard this piece by Yuri Falik, I spent a few minutes on my hands and knees, looking for my jaw as it had dropped off and rolled under the sofa. The wildly stark and singularly beautiful harmonic juxtapositions and sheer expressive intensity I found literally transcendent. It is yet another example of the seemingly bottomless well of utterly extraordinary music made in the Soviet Union, despite all the crippling strictures of socialist realist dogma, that remains to a large extent completely unknown in the West.

Yuri Falik: String Quartets Nos 3, 4, 5 and 6. The Taneyev String Quartet. © Northern Flowers

4: David Wynne (1900-83):

String Quartet No 3 (1966)

David Wynne did not have the typical early life trajectory that is common to many composers. Born a shepherd's son in south Wales, by the time he had reached the age of twenty-five he had already spent more than a decade extracting coal from the entrails of the Earth. It was only at that age that he received a scholarship to study music in Cardiff. These early years may have been enough to give his music that most valued quality in my book: individuality, which is wonderfully on show in this quartet, the third of five he wrote in his life. His terse musical expression finds a perfect vehicle in the string quartet, at least in this particular example.

Ian Parrott, David Harries and David Wynne. University Ensemble of Cardiff. © Lyrita

5: André Jolivet (1905-74):

String Quartet (1934)

André Jolivet may not be in the front rank of French twentieth century composers, but neither can he be considered a forgotten one. Despite the multiple recordings his music has received over the decades, his one and only foray into the domain of the string quartet remains a well-kept secret, which is a real shame because it is an absolute gem.

André Jolivet: Quatuor à cordes; Suites rhapsodiques; Nocturne; Cinq églogues. © Saphir Productions

Like so many of the best examples of this genre, it does not reveal itself completely on first listening but reveals enough to make one want to return again and again and again, each time offering something new, enjoyable and worthwhile.

Copyright © 22 January 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain