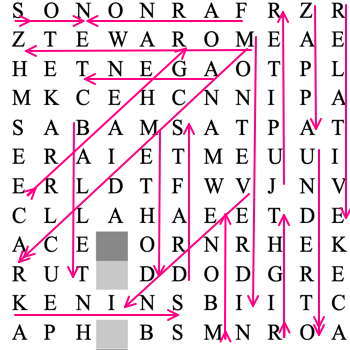

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

Packed With Good Things

RODERIC DUNNETT reports from the

2019 Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester

Beethoven's Ninth seemed perhaps, like Verdi's Requiem, a crowd pleaser aimed at filling seats and offsetting the marvellous, daring choice of the rare La damnation de Faust. To have The Armed Man and a Chilcott commission and premiere might also seem to verge on popularism. But the performance of these others was even more splendid than the works themselves.

A view down the packed nave of Gloucester Cathedral as Adrian Partington directs the soloists in Berlioz's La damnation de Faust. Photo © 2019 Michael Whitefoot

And so it was with the Beethoven Ninth. If Partington's opening Berlioz Faust was incredibly exciting and - despite its gentler moments - forceful, explosive and vividly dramatic, with its intermittent textual and orchestral flurries, and disconcerting, haunting passages of scarcely concealed intimidation and menace, the Beethoven surely matched those high standards.

The Philharmonia, for whom the thunderous work must have seemed like an old friend, played almost effortlessly, but with muscular energy, dynamism and impetus, the choir, under its conductor's stylish urging, displayed, in the raging last movement, a stamina that lifted the work onto a high plane. So too the soloists, most especially David Stout, who played the rumbustious, turbulent bass role in the finale.

The opening buildup, that which follows, and that near the close, thrusting urgently, the almost dancing sequences that follow, the intermittent soft woodwind and chirpy flutes, the hushed, mysterious link passages, the verve of the lower strings, and the wonderful unwinding feeling near the end, all demand careful pacing and meticulous precision. The folk-like second movement - Haydn was Beethoven's teacher - abounds in salient silences, contrasted with chattering woodwind, not least bassoons, notably in the trio, where horn calls too emphasise the folk feel of the insistent vivace (indeed 'molto'), where the phased passages feel like refined stanzas.

The strings need scrupulous nursing in the Adagio, if it is not to drag; here they moved lightly, aching but not ominous, and when the violins' main melody emerged, adapting to a kind of variation, the exquisite pacing proved we could surely have been in Mahler. The interludes - bassoons and clarinets especially - were pure delight; and the bemoaning falling semitones before the final blast were besotting. The Philharmonia's urgent, even ominous lower strings, both assertive and interrogative, heralded the solo bass and chorus entries, and the full orchestra with blatant brass could almost be a Hymn of Joy in itself.

The high placed, stretching tenor solo - Andrew Staples, a Three Choirs regular - is almost pained in design; but it is essentially enraptured, as it was here. Held back by Beethoven till now, the chorus captured the full thrilling impact as it flamboyantly joined the four hurtling soloists. Popularist or not, one can only say that Beethoven's greatest symphony, pairing vicious outbursts with unforgettable lilting melody, was granted an exciting, explosive performance by all forces, choir, orchestra and indeed Partington, bringing all his wide experience to the conductor's role. He fired them all up to a stormy, nerve-racking, electrifying performance, and that is what the huge audience in nave and side aisles will have found most gratifying.

The four soloists, Ilona Domnich, Catherine Wyn-Rogers, Andrew Staples and David Stout in Adrian Partington's sizzling performance of Beethoven's Choral Symphony. Photo © 2019 Michael Whitefoot

The Festival does, indeed has to, look far ahead, says Alexis Paterson. 'We've already largely mapped out Worcester 2020 - indeed even Hereford 2021 is in our sights. Designing repertoire is inevitably quite a jigsaw! But with Samuel Hudson, Worcester's new organist, in charge - he and I shared a lot of ideas by email, Sam being still organist in Blackburn - I think a pretty amazing programme has emerged, embracing some surprises!'

The Three Artistic Directors of the Three Choirs Festival - Adrian Partington (Gloucester), Geraint Bowen (Hereford) and Samuel Hudson (Worcester). Photo © 2019 Michael Whitefoot

Indeed the forthcoming Worcester programme, Samuel Hudson's first as Artistic Director, was announced at this year's Festival. Vierne crops up at the Festival Opening Service/Eucharist, and in David Briggs' ensuing organ recital. A new symphony (by James Francis Brown, honed by a Viennese pupil of Berg) is premiered; there are new works from Hong Kong-born Dani Howard and Gabriel Jackson (whose recent Stabat Mater also features). Horatio Parker's Hora Novissima (1893) regains life - what an initiative that is, including this Massachusetts-born Elgar contemporary, and one who taught at the National Conservatory in New York at exactly the time that Dvořák was its Director - just over a century after his death; Adrian Partington in another terrific innovation, conducts Cecil Armstrong Gibbs' unfamiliar hour-long Odysseus, arguably the greatest (certainly choral) work by a composer who has seemingly not been heard at the Three Choirs before. The three Cathedral Choirs sing Buxtehude; and the Gabrieli Consort, Purcell's King Arthur. Elgar is there - The Music Makers, whose quirkiness and nostalgic quality can evoke varied responses. But if that isn't shrewd, bold and original programming, what is?

Copyright © 31 August 2019

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK