- Leó Weiner

- September 11th 2001

- St John's Church Buxton

- Georg Philipp Telemann

- Giselle Allen

- John Scott

- Easter Monday

- Celia Craig

Packed With Good Things

RODERIC DUNNETT reports from the

2019 Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester

One commendable aspect of this 2019 Gloucester Festival is that it gave a generous share to young people. Even the Philharmonia itself fielded a quartet of Young Performers, in an eclectic hour-long programme of eight works. The Karl Jenkins oratorio involved to a large extent the Three Choirs Festival Youth Choir, initiated by Partington and which from the very start has produced shining results. There was the large children's participation in The Burning Boy, possibly the first time a young people's performance has been allowed an early slot. And on the final day, before the dazzling evening's Holst and Beethoven, arrived one of the most moving pieces, at least in its narrative, of the whole week. Carl Davis is best known these days for his amazingly versatile accompaniments to silent films. But he is also a composer of substance. As well as TV scores, film music and silent film music, he has composed, for instance, four ballets. He had lodged in his mind the story of the Jewish children extricated from Nazi Germany in 1938-9, the Kindertransport, before the claws of the brutal regime could claim them. Thousands were saved: from not only Berlin, but Prague and Vienna too. Several plays on the subject have been circulating since Davis was commissioned to write a new work for the Hallé Orchestra a decade ago.

Davis' score, shared here as intended among children or student players, is relatively straightforward, rather than ploughing new territory. It does the job, in what is a special and most meaningful educational revisiting of the horrors, but also blossoming with hope. Hence he deliberately sought to provide comparatively uncomplicated writing - a 'black and white feel' he says, with emphasis on strings particularly, and what he termed a 'rather Broadwayish' vocal line, also taking stock of Jewish melody of the period. As his colleague he engaged Hiawyn Oram, author amongst others of children's books, who generated a text that works marvellously, mainly because the balance between the youngsters' traumatised memories - the initial terror of living under Hitler's vindictive regime, the tragedy of those who were left out of the means of escape, and the nervous arrival in a new country supplying historical context, or what Oram describes as a 'dramatic narrative' - and a series of sung solos from the young choir were all rather well judged. It's a long piece, falling into twelve sections.

What was evident at every turn was the meticulous drilling of the children. Five 'actors' bore the brunt of the narrative; in the rearground is Germany's annexations of that period - Austria, the Sudetenland, soon to be all the Czech lands. And to the foreground, Kristallnacht, the pogrom initiated by Goebbels, the section building to an almost terrifying crescendo and tuned percussion going wild. The contrasts are vital, and at no point did the conductor, Nia Llewelyn Jones, Gloucester's first ever Singing Development Leader, seem to falter in her choice of tempi, not least in the repeated choruses evoking excitement and apprehension. Her choir came vividly alive at section 4, 'Train Rumours': witness the ironic 'Think of it as a short separation', and the floating, echoing 'Remember to write us ... And we will write to you'. Nia, appointed in 2014, is an inspired choice: she has worked with several leading UK orchestras, and has conscientiously and admirably met her remit to enthuse and encourage children in the diocese to sing. She is indeed a 'revitaliser'. Numbers in the Junior choir have soared. She is also the first conductor of the Gloucester Cathedral Girls' choir, initiated three years ago.

For the text of part eight Davis reserves music distinctly Klezmer-like, with struck percussion as the train, freedom in sight, is imagined meandering through Dutch towns. To the next passage, highly atmospheric, the children's choir brought marked tenderness and sympathy: the ensuing sequence has its own poignancy: 'We feel out of place here - all at sea. But with every knot (the cross-Channel boat's movement) we're further from our darkest, darkest night.' Now the trains are English: to this list of hopeful place names Davis added a splendid, sensitive orchestral intermezzo. There is gratitude to their doomed parents for loyally parting with them, in anticipation, giving them 'second lives'. However the children still fear their Jewish ways may isolate them. But anxiety passes: the choir's ending, fear and doubt put aside, was positively enraptured.

Davis' score, while thoughtfully restrained, just occasionally verged on the bland. Yet the simplicity had merits. It enabled the grim, then optimistic, story to shine through. The children were never swamped; and the extended forces were managed so that the balances as well as the contrasts emerged lucidly: the story, and indeed the dream of a fresh, unthreatened future captured in the text, was beautifully encapsulated. This new sun, it seemed, indeed 'will always rise'.

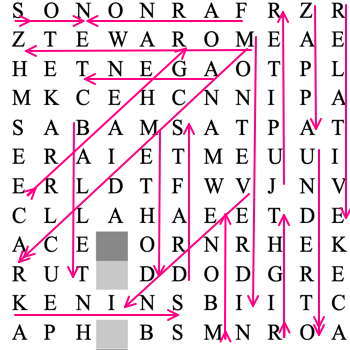

The exuberant sixty-strong Three Choirs Festival Children's Chorus, which made such a moving success in Carl Davis's Last Train to Tomorrow, the story of the Nazi-era Kindertransport. Photo © 2019 Michael Whitefoot

The cathedral was made available for a rather remarkable recital by members of the Philharmonia: the 'Philharmonia Players', who would also play a key role next day in Carl Davis's elegiac Last Train to Tomorrow. Remarkable, because the repertoire was unusual, one of the purposes Partington had aspired to achieve with his 2019 programme. Mendelssohn's older sister Fanny Hensel, who died at only forty-one, and who like her brother eschewed strict Judaism, was not just a superb pianist and piano teacher in her own right. Her output at that age was staggering - over 450 works, including for piano 'Songs without words'. Her Easter Sonata was only identified and premiered two years ago. Her E flat string quartet (1834) runs to nearly twenty minutes, and its high quality, arguably matching her brother's talent, was utterly apparent here.

The same kind of finessed playing brought vividly to life Joseph Phibbs' three-movement Second Quartet. 'Shimmering', 'darker', 'fleeting', 'edgy and fragmented' give some feel of the work's individual and, with Phibbs, always original quality. The start and section heralding the blazing coda enfold the atmospheric slow sections; pizzicato, eloquently captured here, appears both early in the work and later in the attacca middle movement; the shifts of pace from benign to dramatic are especially striking, and demand adroitness and acute listening between the four parts. That the players achieved this so elegantly was much to their credit.

John Joubert wrote his Miniature String Quartet not long after transiting to Britain from South Africa. It lies outside his output of three quartets, one even predating it, which have come to earn acclaim as some of his most personal, innermost utterances. Each runs to between 21 and 24 minutes; this however is only eight minutes, hence 'miniature'. Although written with young players in mind, it's still challenging. But the high point of this fresh and appealing concert was Felix Mendelssohn's Octet: he was scarcely sixteen when he penned it - like his sister's quartet, in the key of E flat. The players demonstrated what boldness and exquisite interplay (plus ample solo passages) make up this, despite its youth still one of Mendelssohn's most beautiful and alluring works. Con fuoco designates the first movement; and leggierissimo then scherzo. What cheek to produce a masterpiece such as this in your mid-teens. This was a sunny performance to relish intently; what appetising programming to include a masterpiece with eight instrumentalists such as these.

This was not the final instrumental chamber concert. With two strings, two winds (both doubling), piano and percussion, the intriguingly named Dr K Consort, formed a decade ago at the Royal College of Music, on the last Saturday served up an eclectic programme involving nine composers. Most were short works, from three to six minutes; embracing, we are told, 'stories' from across the world. One most welcome, vital piece came from Peter Maxwell Davies, his Dances from The Two Fiddlers, a young people's opera that is shamefully and mistakenly neglected today. Lithuania, Anglo-Saxon and Roman Britain, Orkney, South Italy (Calabria) are among those evoked. The range of orchestration and instrumental timbres achieved by these disparate, individualistic composers proved especially gratifying; and before three very early pieces by Holst, an exploration of 'Carnatic' oriental patterning by violinist Alice Baron proved astoundingly evocative.

The composers: the ever-original Howard Skempton; Australian-born Sadie Harrison, who has been Composer in Residence with the Afghan National Institute of Music, as well as holding such roles in America and (currently) Germany; Jeremy Thurlow, who has held a clutch of roles in Cambridge; Royal Philharmonic Prize winner Stef Conner; Thomas Simaku, born in Albania and now part of the pioneering music department of the University of York; and Thomas Albert, at seventy the oldest, an American composer long connected with Shenandoah University, Virginia. It can be seen that the composers are almost as diverse as the stories they choose to reflect. So varied a programme again fits perfectly the aspiration of Partington - and each Artistic Director at the three venues - that the Festival do justice to modern works as part of the mix of events.

By 1901-4 - compare his neglected opera, his fourth work, Sita - Holst, by his late twenties, was becoming drawn to music of the Orient. Most relevant here were the St Cecilia Singers' morning opening work (in southern Cotswold Painswick), Holst's first three choral hymns from his four collections of settings of texts from the Hindu Rig Veda (written originally in Sanskrit). Jonathan Hope conducted, and very proficient his group proved: able to produce atmosphere (notably in three songs by the aforementioned, richly gifted David Bednall lamenting the effects of war, including the most famous sonnet by Rupert Brooke), and where required an ethereal beauty, profundity and a fervent passion wholly appropriate to the works performed. That Hope included Ivor Gurney's 'Sleep' and the first performance of a setting of Gurney's poem 'My County' ('Gloucester, my Homeland ...') by Thomas Hewitt Jones, whose works include three ballets for the glorious young ensemble Ballet Cymru, proved wholly apt for a concert of works involving a string of settings with a Gloucestershire connection. As organist, Hope also provided on the Friday the first performance of his new organ Voluntary The Indivisible Trinity.

Holst, instanced too in another extract from the Rig Veda by the Oriel Singers, was fascinated by the vast collection of choral hymns in Sanskrit, dating from 1500 BC or a little later, some of the earliest texts in any Indo-European language; or in his early opera, Savitri. This year's Three Choirs, in a departure, included - fascinatingly - a clutch of events exploring this and other aspects of (particularly) Hindu music: the expressive, expert, even haunting and mystical, thrumming accompaniment of Sri M Balachandra (on mesmerising double-ended drum); and Balu Raguraman (playing violin, held vertically, on his knee as if a miniature viol). Raguraman's cheerful accompanying introductions were especially invigorating and informative. So were two related lectures, giving lucid background to the Vedas; and equally, an astonishing workshop event on the same subject. Raguraman spoke passionately - and communicated wonderfully - music and rhythms from the twirling Mahabharata tradition, carried along with their narrative content, which provided the world's longest poem, some 100,000 couplets long. The roots of the epic poem easily reached back earlier than Homeric times, offset by the Carnatic (Karnātak) tradition centred on Andhra Pradesh and other South Indian states.

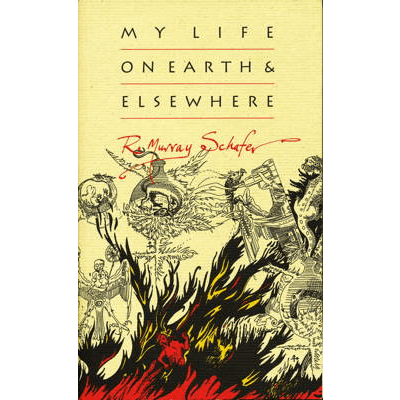

Bali Raguraman, playing the vertical violin in a mesmerising instrumental recital with Sri M Balachandar, beautifully expressive on the mridangam (oriental double drum). Photo © 2019 Michael Whitefoot

This fascinating focus on Indian traditions, a new departure, stemmed largely from the Festival's Chief Executive, Alexis Paterson, who explains, 'I thought carefully about the wisdom of placing the sacred texts into this hallowed Christian setting: I hope the material selected by tonight's chanters will celebrate our common ground: our humility and awe in the face of creation's complexity.' Wise words; and how right she was: these occasions unveiled new sounds, new knowledge, and a mystical and saintly vision of the beyond.

Review continues on the next page >>

Copyright © 31 August 2019

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK