- Ulf Söderblom

- Multi-Faith Centre

- Innova

- John Jeffreys

- Keiko Takano

- tuba

- Menahem Pressler

- Central England Camerata

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

VIDEO PODCAST: Come and meet Eric Fraad of Heresy Records, Kenneth Woods, musical director of Colorado MahlerFest and the English Symphony Orchestra and others.

VIDEO PODCAST: Come and meet Eric Fraad of Heresy Records, Kenneth Woods, musical director of Colorado MahlerFest and the English Symphony Orchestra and others.

Packed With Good Things

RODERIC DUNNETT reports from the

2019 Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester

The Festival's first event, at Tewkesbury Abbey, was thus a concert devoted specially to MacMillan. He was not alone, however: Gabriel Jackson is one of the finest, and most productive, sacred choral composers today. Telling larger works include a Requiem in 2008, his Mass for All Saints in 2016, a Stabat Mater in 2017, plus numerous sacred and secular choral and chamber works, and an applauded Piano Concerto in 2009. His early works date back to the late 1980s, and he has been marvellously vigorous not just in generating music, including numerous anthems, but by his example encouraging others to enter the sacred music field. 'Countless and wonderful are the ways to praise God' was the finely crafted piece in question here.

It was actually for the choir of Merton College, Oxford, the performers of this exalted concert in Tewkesbury Abbey, that Gabriel Jackson composed his Stabat Mater. This initial concert also included two Marian anthems (on familiar texts, Ave regina coelorum and Alma redemptoris mater) by Judith Weir, current Master of the Queen's Music, and the Bulgarian-born Dobrinka Tabakova (whose recent works include a set of Canticles for Truro). The Weir work was interesting for its quite forceful, but uplifting central lines, preceded by a bell-like start, the upper voices prominent, the whole building to a dramatic ending, impacting strongly.

The second half of this Tewkesbury concert was given over to MacMillan's deeply expressive setting of Seven Last Words from the Cross. In fact, the Eucharist and Opening Service were preceded by two substantial, well attended and notably successful events, both allotted to Tewkesbury Abbey.

MacMillan featured here at Tewkesbury in both the first and the second halves. The former convinced one that his eleven-minute Miserere - it feels much longer, and indeed one wishes it was - is one of the most striking and original works in his entire output, in any genre. It is haunting: the parallel rising motif (in the men's voices) which begins it, and returns later, is unbelievably beautiful, yet also penitential. The Miserere involves forty-two lines of straight text, quite a challenge to keep interesting and well structured. Parts are declamatory, and more than once, in the girls' voices especially, he introduces a form of modified appoggiatura, possibly relating to the Scottish 'keening' or 'lamenting' he has often used before, and is of course especially apt here. Periodically he breaks into a form of Plainsong. There is a great and growing tenderness, affected by major-minor alternations. Latterly, 'Sacrificium Deo spiritus contribulatus', where the sopranos fall to total stillness over chords in the men's parts, proves a truly magical moment, and extends for the remaining five lines.

Four works from James MacMillan's ongoing output of sacred music were included by Partington in the Wednesday afternoon Evensong (sung by the three Cathedral Choirs), recorded and broadcast live by the BBC. They were 'Benedicimus Deum caeli' used as an introit; 'O give thanks'; his Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis; and 'Meditation' for organ - founded on Gregorian chant, to which he was increasingly drawn during his decade as Director of Music at St Columba's Roman Catholic Church in Glasgow. There was more MacMillan, keyboard music, for the authoritative John Scott Whiteley, a pupil of Fernando Germani and Flor Peeters, and very rightly dubbed here as a celebrity, being one of Britain's most accomplished soloists - witness his late night TV series on Bach. Scott Whiteley, who served as assistant organist, latterly organist, at York Minster, paid his own tribute to MacMillan. Alongside Charles Tournemire and the twenty-five-minute Symphonie in B flat minor by Pierre Cochereau (1924-1984), the renowned organist of Notre Dame Cathedral, and an immensely prolific composer and recording artist, Scott Whiteley played two MacMillan pieces, 'Gaudeamus in loci pace' and 'Toccata' - a premiere, enclosing three 'Dances' and a Coda, based on the thirteenth century ancient hymn 'Pange lingua gloriosi, corpus mysterium' by St Thomas Aquinas for the Feast of Corpus Christi.

The musically excellent and astute conductor of both halves of this choral recital at Tewkesbury was Merton's Director of Music, Ben(jamin) Nicholas. A former Organ Scholar of Oxford's Lincoln College, son of the then Organist of Norwich Cathedral and generator of a brilliant, almost unmatched sound from the Tewkesbury Abbey Schola Cantorum (boys' choir) - so in a sense this was 'coming home' for him - Nicholas was an inspired choice for Merton, assisting then taking over the torch from their choir's founder Peter Phillips. It was already a promising choir, with girl undergraduates rather than boys, but Nicholas' inspiring leadership and remarkable gifts were instantly obvious. He has quickly taken Merton to the level of, even beyond, the three main boys' colleges - Magdalen, New College and Christ Church. Merton choir is gifted, committed, precise, perceptive, and all of this is due to the inspiration generated by Nicholas.

You could feel his sensitive conducting all through the main work, MacMillan's Seven Last Words from the Cross. Well-timed silences were part of the emotive unfolding. Strings figure large: meandering strings underline the first part; then atmospheric low strings and skittering upper strings ('Woman, behold thy Son!'); then pianissimo strings. At 'Ecce ligneum' (the wood of the cross) the men sing darkly over a persuasive double bass, the competent chamber orchestra being here the Bristol Ensemble. MacMillan evokes a real tenderness, high tenor especially enticing, at 'Verily I say unto thee' (to the sympathetic robber).

Benjamin Nicholas draws beautifully sensitive performances of James MacMillan and Gabriel Jackson from the now renowned choir of Merton College, Oxford. Photo © 2019 Michael Whitefoot

A thrumming, tragic interlude prefaces Christ's anguished cry 'Eli, Eli, Lama Sabachthani' (My God, why hast thou forsaken me?'). Both this and the subsequent 'I thirst' are dark and gloomy, the latter gaining intense tragic impact, marvellously elicited from the Merton choir, from the sensitive adagio - one might call it adagissimo - at which Ben Nicholas took it, and to which his choir responded with finessed attentiveness. A massive clustering buildup, above all in the strings, concludes. At 'Father, into thy hands', moments of 'keening'-like decoration - a Scottish mode of 'wailing in grief' - surfaces before a carefully managed fade to pianissimo and fadeout in the strings. No wonder this work is so admired, especially in as perfect a performance as this. There was yet more: MacMillan's Kiss on Wood, for violin, appeared alongside Howells, Gurney and the substantial Violin Sonata by Welsh composer Grace Williams, in Madeleine Mitchell's mid-afternoon recital.

Grace Williams (1906-77)

Another visit to Tewkesbury featured drama, presented by a mixed ensemble - professional adult singers, some teenage soloists, and a notably fine seven-strong ensemble - to perform The Burning Boy, a work based on an idea and a text by the late Gloucestershire poet Charles Causley, which reflects Causley's love of countryside and rural folklore, and composed quite recently by Irish-born (and Wales-educated) Stephen McNeff. I didn't know McNeff's work at all before this, and now I know what I've missed. His ingenious instrumental handling had all the delicacy of a lightly scored Church Parable, but most importantly, the whole work benefited from the subtlety of his scoring for a mere seven instruments.

Not all was shy, pastoral and innocent: indeed the beginning was quite wild, even disconcerting: a kind of squeal or screech. Perhaps the only criticism of the presentation - if one is needed - was that the sound early on obscured the soloists' text - though it might as easily be argued that the soloists - except one, the Farmer's Wife, Trinity Laban's Kay Huntley, who early on tended to overbear the orchestra! - did not project sufficiently in the spacious Abbey acoustic. The smallest children seemed a bit lacking in confidence, so that even they were overborne too.

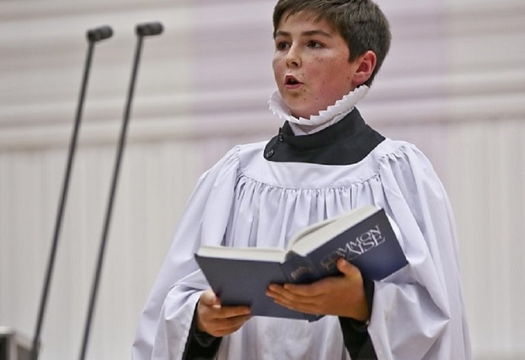

With a piccolo and bass clarinet (plus some inspiring percussion) to vary the textures, McNeff produced a sparkling, multi-coloured, beautifully inspirational accompaniment - by turns legato and lulling, pointilliste and piquant, animated or subdued, pure or fierce, with an instrumental refinement that never ceased to delight. The story would have carried across better had the words been supplied, or if the superior enunciation of bass-baritone Paul Carey Jones had been matched by the others, who only impacted when placed or moving among the audience, in the fairly basic but perhaps adequate staging by Edward Derbyshire. But the younger soloists were exemplary. Two young women or girls, currently or recently at London Colleges - Charlotte Levesley (ex-Trinity Laban) and Johanna Harrison (Guildhall) shone, bringing a delicious light touch to their 'Harvester' roles. Tenor Oliver Vincent (Gehazi) made some impact, with able projection, but along with Carey Jones the best voice of the afternoon was Cassian Pichler-Roca. A Tewkesbury Abbey chorister, schooled at Dean Close, he won BBC2's Young Boy Chorister of the Year in 2018. No wonder. Gorgeous (especially low) timbres; a beguiling voice: what an astonishing rare talent.

Cassian Pichler-Roca, boy winner of the 2018 BBC Radio 2 Young Choristers of the Year Competition, and young star of Stephen McNeff's stagework The Burning Boy

There followed one of the most thrilling events of the week. The Sesquicentenary (150th) of Berlioz's death, in 1869, featured in three tributes: his exquisite cycle Les nuits d'été (in which Martyn Brabbins and mezzo Kathryn Rudge, brought out the sheer delicacy of the gossamer-like poetry of Théophile Gautier); his overture Le carnaval romain; and his semi-opera/oratorio La damnation de Faust, drawn selectively from one of the composer's heroes, the Weimar polymath and poet, (Johann Wolfgang von) Goethe. He based this tragicomic play on an eighteenth century - but surely earlier - German legend, in which Faust aspires to attain worldly knowledge, pleasure, and power at the expense of his soul.

It was conducted by the Festival's Artistic Director and prime mover, Adrian Partington, whose insistently spot-on timing, piercing intelligence, total command using a small baton, and versatility in choosing pacing and balances - not least for a phenomenally on-form chorus - ensured an excitingly driven and gratifyingly conceived performance. All this was transfigured by the sparkling brilliance of the Philharmonia Orchestra, in residence all the week and here pouring forth stupendous talent from every section. Indeed the quality of all forces was in evidence in buckets. He had chosen to make this challenging score his opening pitch, and the outcome was in every respect superlative.

The work had in fact been heard once before: its first outing at the Three Choirs, at Gloucester in 1995, under the heartily Francophile then Music Director, David Briggs. But this was a significant commemoration. Above all, Partington had chosen three soloists of exceptional talent. Susan Bickley, as always excellent, incisive and touching, sang Faust's idealised love, the temporarily doomed Marguerite - in the original, Gretchen. The pair's extended, enraptured duo is interrupted by the snaky Devil (Mephistopheles), whose pernicious aim is to prise Faust away from his idealised love - 'Love has taken possession of my enraptured soul, ... to lose you is to die'. Bickley's Marguerite has two long stanza arias, in which she expresses her passion; but soon she has lost - 'He comes not. Alas! Alas!' Soon Marguerite fades from the story, having uncharacteristically fed her mother a poison supplied by Faust. She will be condemned to death. However all is not lost: her apotheosis concludes the whole work.

The tragedy and poignancy is expressed in the score, and was captured finely in these sections in this fragile, sensitized, admirably judged reading. There are several well-contrasted choruses - peasants, the condemned, soldiers, students (to whom Faust of course belongs), and before that, more peasant songs, Christians, drinkers, gnomes and sylphs (a curious mix), neighbours, celestial spirits, and bizarrely impish 'Will o'the Wisps', Mephisto's acolytes, all musically differentiated. But apart from a curious, jaunty, boozy solo from 'Brander', not entirely satisfactorily projected and surely failing to capture the comic underlay, by David Ireland, the brunt of the solo work was taken by a superb Faust, Peter Hoare, searingly intense and soaring to dizzying heights. He is beset by a host of (partially) benign influences, and latterly obsessed by his muse, the compromised Marguerite, whom he ultimately - and fatally - abandons.

It was they who delivered the most dramatic - and betimes hilarious - performances. Each mesmerising individually, Faust, distressed: 'They are villagers ... In my misery I am jealous of their pleasure.' 'Where in all the world will I find what my life lacks?' 'Who are you, whose burning look penetrates like the flash of a dagger ... my infernal guide?'. And Mephisto sardonically: 'The harm is working; he is ours!' 'I am master of this proud soul for ever'; and 'He signed freely'. His demons bear Mephistopheles in triumph. Above all, in this entertaining performance, these fated antagonists played off each other like a pair of unlikely lovers, with cheeky interplay - naive, malicious or wickedly beguiling; the two bandied entertaining banter, jokey, teasing but often dark and threatening; and their visual interaction was as brilliant as their vocal. The end might be tragic, but the trysting duo contrived a sizzling stage act, so that we did indeed, in this seething, edge-of-seat performance, nursed by Partington with patent assured precision and considerable brilliance, come near to opera.

The devilish Mephistopheles (Christopher Purves) mercilessly misleads the hapless Faust (Peter Hoare). Photo © 2019 Michael Whitefoot

One thing Hoare caught to perfection (despite a curious stance, presumably to hear his own voice clearly intoned, particularly alongside Christopher Purves' vociferous, mischievous and insuppressible Mephistopheles), was Faust's early disillusion, distaste, isolation and in effect loneliness. It is this that enables Mephisto to latch onto him - vulnerable, an obvious victim. Faust - who at one astonishing point soared to what sounded like a tenor top D, perhaps only B or C, may hunt for 'the kiss of celestial love', whereas his opposite, a sneaky liar, glibly asserts himself to be 'the Spirit of Life', a consoler who can penetrate Faust's depths, set up alluring diversions and, ultimately, claims him. But all in all, what a performance: pinpoint precision, fabulous variety, perfect engineering, unremitting vitality. The work is much more biting, one feels, than Gounod's almost naive opera Faust. Mephistopheles here proved far more comic, sinuous and more sneeringly underhand - contrasts that Purves elicited both joyously and infernally.

Review continues on the next page >>

Copyright © 31 August 2019

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK