SPONSORED: An Outstanding Evening - Bill Newman listens to American pianist Rorianne Schrade.

SPONSORED: An Outstanding Evening - Bill Newman listens to American pianist Rorianne Schrade.

All sponsored features >>

- Heather Slade-Lipkin

- Elgar: Cello Concerto

- William Blitheman

- Luciano Berio

- Peter Alexander Goehr

- William Byrd

- Warner Music Italia Srl

- Sally Pinkas

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

Packed With Good Things

RODERIC DUNNETT reports from the

2019 Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester

The Festival's many solo recitals were launched from the very start. The pianist Luke Jones, from North Wales, studied for seven years at Chetham's and now the RNCM, both in Manchester, and picked up a clutch of competition first prizes - in Italy, Slovenia, and at Bromsgrove and in Wales. In his hour-long recital at St Mary de Crypt he essayed Prokofiev's famously tricky half-hour Eighth Sonata, interlocking slow pianissimo, tunefully singing melodies and fearsomely hurtling passages, and a savagely aggressive later presto section and finale as wild as Prokofiev's exhausting Seventh Sonata, famously recorded by Sviatoslav Richter. With it came Chopin and Debussy - all of Book One of Images.

The same day as Partington's sizzling La damnation de Faust, again in Tewkesbury Abbey, on the oft-reconstructed, originally seventeenth century, till recently Walker and now Kenneth Bray Milton Organ - four manual; it even once had five - Scotland-based Steven McIntyre, doubtless a Scot himself, gave the first Festival organ recital. He is assistant organist at St Mary's Scottish Episcopal Cathedral in Glasgow, and was previously organ scholar at Peterborough Cathedral. But he launched his career also north of the border, as scholar at Dunblane Cathedral and Assistant at Paisley Abbey. Last year he picked up the Royal College of Organists' most coveted top Fellowship award, a Limpus Prize.

McIntyre included early on an intriguing tribute to his current home, an organ arrangement of a seventeenth century tune 'Ane lessone upon the first psalm', a relatively optimistic handling prefaced by the melody itself; and followed that with another Scotsman, Rory Boyle, now in his upper sixties: Three Pieces, ending with a joyous Paean. Finally, two movements from Vierne's Symphonie No 3 (not the famous First Symphony's 'Final' or the Carillon de Westminster from the Third Suite), but including another snorting, bustling, swift-moving Final. Given the time allotted - 90 minutes in the programme, but little over 50 minutes in fact, and as McIntyre was, in the Vierne, offering a welcome and compelling change from that normally heard, perhaps the whole symphony might have been included.

A later organ recital was by Christopher Strange who, like pianist Luke Jones, was another Chetham's pupil who progressed from Manchester and Chelmsford cathedrals to become number three at York Minster - Scott Whiteley's long term fiefdom - under Robert Sharpe. Strange included a whole Vierne Symphony - No 1, which does include the scintillating, famous Finale. Especially attractively, to start with, he played a Prelude (including a toccata and fugue) - most distinctively phrased - by the great Nicolaus Bruhns, a forerunner of Bach (more a contemporary of Purcell), son of a town organist, a child prodigy and at sixteen a protégé in Lübeck of Buxtehude, who considered him his best pupil. Bach himself appeared in Anita Datta's recital. She was in fact a pupil of Scott Whiteley, as were many others. As well as some twenty minutes of Jean Langlais, she too introduced a work not often heard, the last three of Sept Improvisations by Saint-Saëns.

Not for the first time, the fabulously proficient Ex Cathedra choir, based in Birmingham and founded and conducted by Jeffrey Skidmore, paid a visit to the Three Choirs. Here just one work was presented: Rachmaninov's fervent and impassioned Vespers (All-Night Vigil), composed during the First World War (1915), which were last performed in Gloucester by Matthew Best's glorious Corydon Singers.

First to acclaim was the tenor solo (cantor), a marvellously expressive and at times forceful voice which offset the choir to achieve, in all quarters, the fabulous standards it rose to in this superbly engaging reading. A mezzo, almost a low contralto, also achieved a comparable moving intensity. Indeed there was not a single weak soloist drawn from the choir: each, in their way, shone, many with rich colouring, and revealed warmly individual voices.

One of the most impressive things always about Ex Cathedra is the perfect synergy between the choir and Skidmore himself. Their response is resplendent, gorgeous and even opulent. It feels like an organism that reacts as one. The solo voices - and often Skidmore, admirably, shares these solo roles around - are wonderfully focused yet melt back into the body of the choir without dislodging the balances or in any way compromising the choir's glorious vocal unity. Even when its forces are sensibly enlarged, as here, they have all the precision and finesse of a reduced chamber group.

Here the Rachmaninov moves from the moments of heightened drama to the quietest contemplation, and indeed somewhere in between, exploring dynamic contrasts - as this ensemble does so superbly - without any sense of these being forced. It's brave of any choir such as this to essay such an extended piece in the original Russian - to which it was just a joy to sit back and listen - not least when the basses have to plumb such depths, as they did impressively. Indeed here, taken as a whole, is an ensemble with striking strength in depth. A couple of the composer's movements perhaps lack the appeal of the rest, but the overall excellence audibly subsisted. It was a concert performance pervading and spellbindingly suffusing the nave and side aisles of the cathedral, but Skidmore ensured it felt more like a liturgical event - as indeed it should be.

Transition in dynamic - eg that from mezzo-forte to forte in the first movement - made a continual impact on the whole. Repetitions - surely crucial - and a wonderful solo taken at an adagio enhanced the second section, sopranos (as always here) exquisitely tuned. Contrast followed: the tenor solo that emerges in part three was fortissimo, in contrast to the same singer, fabulous in the tender ensuing Nunc Dimittis, a gentle rocking in the upper voices nicely picked out. The next Marian anthem again featured solos, beautifully caring, gentle and loving.

In the (here) noteworthy Hexapsalmos ('Glory to God' ... O Lord, open thou my lips'), Jeffrey Skidmore coaxed a big build up into subsiding magically. A magnificent, explosive declamation ('Blessed' ... 'Give praise') characterised what followed. Exquisitely wafting upper voices ascended above, to amazing, mesmerising effect, in 'The Great Doxology', later in which the same mezzo soloist again shone, bringing her warm tones. Skidmore's control of crescendo soon countered by a diminuendo, and a positively bouncy, joyous end made the final movements sparkle rapturously. His decision to engineer a minute's silence at the end of this captivating event had a marvellous impact: it became a part of the performance: a period of intense, deeply moving reflection.

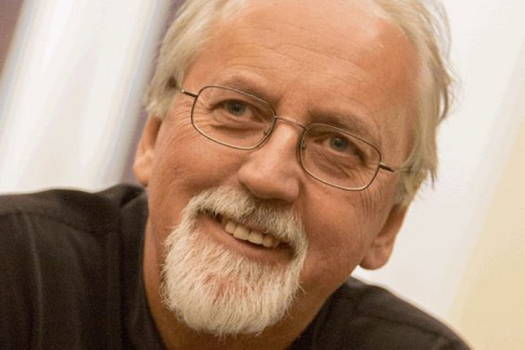

Jeffrey Skidmore, founder of the flawless, exceptional choir Ex Cathedra. Photo © Neil Pughcrop

The Three Choirs prides itself in offering late evening concerts, sometimes different in character. The first was by Alexander Douglas, Tanzanian-born (to Guyanan parents), a very personable and welcoming performer. Jazz is his forte, but not that alone. He has a great gift for improvisation, designated as 'in an African-American hybrid musical language', and earning him the ambiguous accolade 'an unconventional musician' (classicaljazzgospel.com). Gospel and pop are indeed among his outlets, which he deploys, as a fervent believer, 'in the interest of Faith'; all amiably categorised as 'a mish-mash of styles'; while his piano interludes are classed as 'welcome moments of introspection' (The Guardian). Perhaps as a consequence of his belief he is especially committed to addressing mental health issues. Here, African-American music - jazz, gospels, spirituals - were entwined with Bach to generate a new and fresh interpretation, ideal for the late night slot.

If Bach figured in Douglas' varied event, Handel figured late night the next day. The intention was not dissimilar: 'bringing the Baroque into dialogue with contemporary jazz and gospel music'. However, despite an undertaking to include 'more obscure portions of Handel's legacy', the listed items included Messiah, a keyboard Suite, a Concert Grosso, and Zadok. After a rather overelaborate written preface, the most striking comment from Adrian Varela is 'As a Uruguayan native I tired of hearing talk only of Argentinian tango'. Conscious of Bach, Stravinsky and of course Piazzolla, Varela and his band exposed two items, one 'purposely disorientating' and one exploring fugue 'post-Piazzolla'. Like those above it featured a mix, apt perhaps for late night listeners.

Meanwhile two major events, of perhaps more familiar works, had taken place. Verdi's Requiem (1874) had fallen under the baton of Edward Gardner. Given the Festival's tradition, at each of the three venues, of inviting one or two top visiting conductors - Vladimir Ashkenazy, a major coup for Gloucester in 2013, included Rachmaninov's cantata The Bells and Sibelius' stunning solo tone poem Luonnotar - Gardner was a natural choice, having been a boy chorister at Gloucester under John Sanders, and subsequently an assistant to Mark Elder and the Hallé. But all his experience as Music Director of English National Opera, and subsequently in Bergen has paid off: he will be Principal Conductor of the London Philharmonic from 2021.

Gardner delivered a scorching reading of the Verdi. One might expect a suitably explosive reading, and - compare the celebrated performances of Carlo Maria Giulini, rated (at the time) as the best - it must be blistering. It had all the qualities: the blasting, recapitulated Dies Irae, Rex tremendae majestatis with its uncompromising predictions of doom, the Sanctus. The soprano (the exquisite and powerful Korean Hye-Youn Lee), lulling and growing in strength in the initial Requiem, positively terrifying - then reassuring - in the Libera me, shone. A suitably damning chorus exploded in its own fugue on the same words. The alto's proclamatory Liber Scriptus (with its threatening, expertly hushed 'Nil inultum'), was repeated ominously. Christine Rice, leading the Lacrimosa, and Recordare (and later in the scintillating soprano-mezzo duet); the exquisite intoning, led by the tenor (Jette Parker alumnus David Butt Philip) of the moving Offertorium, in succession to his guilt-ridden, pleading Ingemisco; that floating upper voice duo (plus tenor added) in the Agnus Dei especially; and the solo quartet sequences without exception, this reading reached a boiling intensity. The excellently enunciated Confutatis maledictis came across pretty much like Don Giovanni's Commendatore.

With his experience in the ENO pit, and of heading performances of the more substantial and tough to master Verdi operas, Gardner was wholly on top of a score such as this, and many of the chorus doubtless knew this work already, which gave him and them a head start. The playing of the Philharmonia - not just the endless brass, but one bassoon solo, or flute(s) ushering in and concluding the Lux aeterna, especially shone out - reflected this too. Both a familiarity and a freshness opened up a performance of tremendous force and at the opposite end, penitential and sensitive.

Edward Gardner, former Gloucester Cathedral boy chorister, conducts a nerve-racking performance of Verdi's Requiem, drawing fiery results from the chorus and orchestra alike. Photo © 2019 Michael Whitefoot

For those attracted equally to orchestral music, there was (as traditionally) one such concert. Stravinsky's Firebird Suite and Walton's dazzling First Symphony both posed no problem for the hardworked but resolutely on-form Philharmonia. Martyn Brabbins arrived to conduct the Three Choirs' annual orchestral concert. Both of these works received appropriately forceful, indeed electrifying readings.

But Adrian Partington was determined to give Berlioz's 150th a truly warm celebration, and it was Les nuits d'été that especially entranced this audience. Berlioz's score is endlessly exquisite, even the lamenting 'Reviens, reviens, ma bien-aimée; Comme une fleur loin du soleil', or the lugubrious funereal 'barcarolle' 'Sur les lagunes: Lamento: 'Ma belle amie est morte: Je pleurerai toujours' and the grim penultimate 'Au cimetière'. The poet, rightly lionised in his day, was Théophile Gautier, to whom - significantly - Baudelaire dedicated his most influential collection, Les Fleurs du mal. The Philharmonia knows the Stravinsky backwards, and their flair in the Walton suggested that, too. But in the Berlioz an acute sensitivity is required, and Brabbins, himself a Gloucestershire man, won his spurs in prising from them the delicacy that makes this half hour cycle so acutely sensitive and special.

Review continues on the next page >>

Copyright © 31 August 2019

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK