- Tomás Marco

- Jules Eskin

- Tafreshipour: The Doll behind the Curtain

- zither

- Glinka

- Luigi Dallapiccola: Due Liriche di Anacreonte

- Charles Macpherson

- South Bank

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. True Command - James Brawn plays Bach, Liszt, Musorgsky and Rachmaninov - recommended by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. True Command - James Brawn plays Bach, Liszt, Musorgsky and Rachmaninov - recommended by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

Randomness Run Riot

Apart from what everything I write about here has in common, this week's chosen pieces have no more to link them than sheer haphazardness. The selected works owe their origin to nothing more humdrum than the time of year, to what I see outside my window, to some home thoughts from abroad due to the date and simply to what I have been listening to, and enjoying, this week. There is every chance that this woeful slapdashery in the selection process will become the norm from here on in. Don't say I didn't warn you. I will end this week's introduction with the caveat that although the reasons why the pieces of music which have been chosen this week may be mundane, there is absolutely nothing banal about the music itself.

1: Raffaele d'Alessandro (1911-59):

Symphony No 2, Opus 72 (1953)

Born, as he was, on 17 March, tragically the same day on which he died a mere forty-eight years later, to an Italian father and a mother from the canton of the Grisons - the canton that makes up the south-eastern chunk of Switzerland - in the town of St Gallen, a town named after one of the Irish monks that contributed so much to the christianisation of early medieval Europe, I don't know how young Raffaele d'Alessandro, in proper onamastic tradition, wasn't christened Patrizio. Due to his noble determination to live solely by his music and musicmaking d'Alessandro struggled to keep the wolf from the door throughout his short life. I don't know if these continual hardships contributed to his heart prematurely giving out on him but it seems highly probable. This symphony demonstrates just what an excellent musician he was despite the fact that the world seemed mostly uninterested. It has great dynamic drive with wonderfully transparent textures and a very personal palate of colours. Its contrapuntal clarity probably owes a debt to his esteemed skill as an organist. Don't let my talk of transparency and clarity make you think that there is any lack of emotional power and depth because that is all here too.

Grischuns Dal Cor - Derungs, D'Alessandro, Waespi, Juon. © Claves

2: Pierre Hasquenoph (1922-82):

Pentamorphoses (1969)

Yet another invisible man of music. In this case the disappearing act was so well executed that I had to call upon the expertise of my editor to find any appropriate image to include here. I couldn't use any image of the specific piece of music because it has never been recorded, quelle surprise! Just like in the case of d'Alesssandro, from a young age Pierre Hasquenoph knew that music had to be his life and as with Raffaele he had to struggle to make this a reality in the face of strong opposition from his parents. For their sake he started studying medicine until he realised he literally couldn't stomach it. He eventually managed to find a job in French Radio which enabled him to dedicate more time to composition. Due to various rejections of and indifference to his music along with the burden of having to endure Parkinson's Disease, from what I understand Hasquenoph took his own life a matter of months before he reached the age of sixty. Pentamorphoses shows as well as anything I have heard the unique and powerful voice of Pierre Hasquenoph. It is a piece written for harpsichord and eleven stringed instruments. Without being radical it has a modern sound. Messiaen comes to mind in the slower sections. The variety of colours, moods and textures he manages to extract from a mere twelve instrumentalists is extremely impressive and beguiling. The integration of the harpsichord and strings likewise speaks of a composer with a very developed and individual sense of sound and structure. All quite wonderful. I expect a spanking new recording on my desk first thing Monday morning, merci.

Pierre Hasquenoph (1922-82)

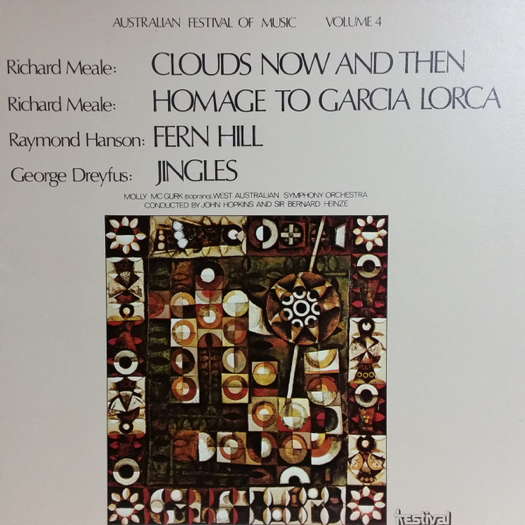

3: Richard Meale (1932-2009):

Clouds Now and Then (1969)

Clouds now and then

Giving man relief

From moon-viewing. - Bashō

Any regular readers of this column - yes I mean both of you - will know that any piece of music inspired by clouds will always get my vote. This one by Richard Meale, in its linking of a seventeenth century Japanese poet and an Australian twentieth century composer, just shows the immemorial power of this planetary phenomenon to leave us awestruck. Indeed such is the universal attraction of clouds drifting across the moon that Bashō's haiku can't help but make me think of tresaured lines from great Irish poet Seán Ó Ríordáin's An Peaca:

Thit réal na gealaí i scamallsparán,

go mall, mall, faitíosach,

Mar eala ag cuimilt an locha sa tsnámh,

Is do chuimil go cneasta an oíche.

Or of that magical painting Moonlit Night on the Dnieper by Pontic Greek/Ukrainian/Russian wonder Arkhip Kuindzhi. As someone who spent many nights camping in the Wicklow mountains as a teenager where I experienced the full glory and occasional terror of the pre-electric night, I feel somewhat melancholic about nature's gift of a moonlit cloudy night's power to continue to inspire awe in a world ever more flushed with artifical nocturnal illumination. As for this piece of music, it's a little moonbeam of magic.

Richard Meale: Clouds Now and then; Richard Meale: Homage to Garcia Lorca; Raymond Hanson: Fern Hill; George Dreyfus: Jingles. © 1972 Festival Records

4: Teresa Procaccini (born 1934):

String Quartet, Opus 45 (1969)

To end my completely coincidental trio of pieces from that annus mirabilis of 1969 I have chosen this little Italian gem. Many of Teresa Procaccini's pieces deserve to be here but I chose this one as it seems to encapsulate so much of what she as a composer is all about, at least as it seems to me. Its three movements last a total of eight minutes. But rather than feeling short-changed at the end, you are left asking yourself was that really only eight minutes? How did she manage to get so much music into so little time? She has a tremendous sense of the right gesture. Knowing when to stop or change before any idea overstays its welcome. She doesn't try to squeeze every last drop out of an idea or stretch it beyond breaking point. As an old song says: 'Say something once, why say it again?'

She also has a heightened understanding of colour, of what sounds sound good and on what instruments. I don't know but I suspect a lot of this seemingly natural ability has been honed over her many years of teaching composition, most notably in Rome's Santa Cecilia. This string quartet was written in her native Puglia when she was thirty-five. She will be ninety next year and it is only in the last couple of years that her incredible productivity - 258 works as of 2020 - seems to be showing any signs of slowing down.

Teresa Procaccini. © Edizioni Edi-pan

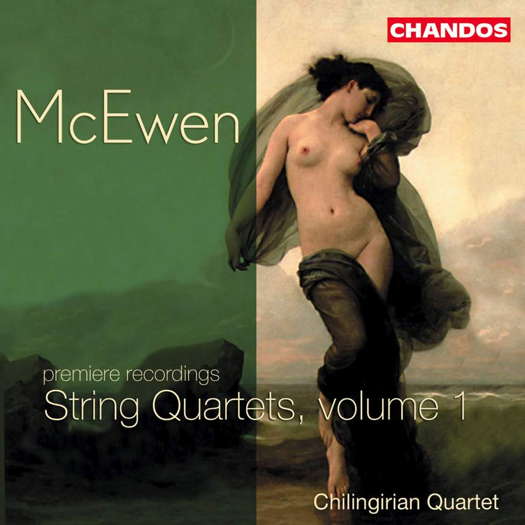

5: John Blackwood McEwen (1868-1948):

String Quartet No 7 (1916)

I finish today with yet another string quartet from a composer who made no fewer than seventeen contributions to the genre. This particular quartet is one of the best examples I know of how to fuse folk music with more classical forms. The last movement is an absolute marvel. It is based around the old tune Flowers of the Forest which was written to commemorate the Battle of Flodden in 1513 fought between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England which resulted in victory for the English forces and the death of Scotland's king James IV, the last monarch to die in battle on the island of Great Britain.

McEwen: String Quartets, Volume 1. Chilingirian Quartet.

© 2002 Chandos Records Ltd

I am completely unaware of John Blackwood McEwen's stance, if any, on the whole affair but as this quartet is subtitled 'Threnody' and it was written in 1916, I like to think of it as a fitting lament for all those who died during the Easter Rising in Ireland that year and for those who were subsequently put to death by the British government.

Copyright © 19 March 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain