- Victor De Sabata

- BPSE concert series

- harpsichord

- Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

- Verdi: Ernani

- Mieczyslaw Weinberg

- Taipei

- Prussia

The Mouth of Hell

If you ever happen to be in the Eternal City and find yourself being driven demented by the noise, the incessant traffic, the oppressive heat or people aggressively trying to sell you things you expressly do not want every time you sit down to take a breather, well you could do a lot worse than head north to Viterbo and then due east to the little town of Bomarzo, on the outskirts of which you will find one of sixteenth-century Europe's most imaginative, intriguing, mysterious and idiosyncratic constructions: The Sacred Grove.

I am not going to spoil the surprise by telling you, if you happen not to know already, what you will find there. All I will say is that Il Bosco Sacro was a child of the imagination of Pier Francesco Orsini, the Duke of Bomarzo at the time. What awaits the visitor on entering this enchanted enclave of exuberant imagination has bewitched and inspired many. Many indeed who possessed extraordinarily fertile imaginations of their own. None however in possession of one quite like that of Alberto Evaristo Ginastera.

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983) in circa 1960 by Annemarie Heinrich

Flesh made of sin. A life lived surrounded by monsters that mirror his soul. A life full of glory and all its rich rewards worthless in comparison to a child who possesses nothing except his harp and his song for the simple reason that the child possesses peace, something the Duke of Bomarzo has never known. Drinking from a chalice to imbibe immortality but in which only lives death and betrayal. The bringer of shame to his esteemed family. He can't abide mirrors. They never allow him to be free of himself. He is Bomarzo. Bomarzo is him. Only his portrait frees him of himself; his shame. He longs to be his painted image. The only one who knows him and whom he loves. Not for him the strange, hermetic, subtle mystery of love. He spilled purple wine on her dress. Don't you see the demon, Julia? No, my duke. All is dream. Dreaming uselessly. Where is the truth? Where is the light? Ah minotaur my beautiful, horrible brother, my terrible mirror. If you want to know about me, listen to the rocks as the moon silently kisses them. Each of those rocks has a mist-made heart. I am their blood. Betrayed by infatuation. Revenge waits in the darkness. Drink my duke and with a child's kiss it ends.

Pier Francesco Orsini (also known as Vicino Orsini) (1523-1583), depicted in the oil-on-canvas Portrait of a Gentleman in his Study by Lorenzo Lotto

My somewhat free-form personal synopsis in the paragraph above is how the imagination of Argentinian novelist Manuel Mujica Láinez envisioned the life and fate of Pier Francesco Orsini in 1962 and from which he extracted a libretto for Ginastera's second operatic adventure five years later. The opera, once filtered through the dramatic and musical imagination of the composer, has as much to do with the modern world as it does with Renaissance Italy and the plight of modern man and woman in general as it does with the Duke of Bomarzo. Indeed although the setting may be sixteenth century central Italy, the feverishly Freudian ferment of 1960s Buenos Aires I don't think is too far away.

Sadly, but predictably, most commentators on Ginastera's Bomarzo focus exclusively on its sensational, circumstantial but least fascinating aspects. Namely its sexual overtones and the fact that its programmed premiere in Teatro Colón was banned by then Argentinian dictator Juan Carlos Onganía. Far more fascinating is the modern psychological and metaphysical aspect of the opera. How we deal with trauma, particularly childhood trauma as individuals. The violence and cruelty with which we treat each other, even, or especially, the ones we are supposed to love. In the context of its time and place – 1960s Argentina – I don't think it is too far-fetched to see reflected in Bomarzo an analogy of how a dictatorial state treats and abuses its citizens - how one suffers and is made to suffer for simply being different, especially when this difference is out of one's control and not of one's choice, which one must bear as one's birthmark. Ultimately, and there is nothing specifically modern about this, there is our extreme and irredeemable anguish in the face of the fact of mortality.

I have never read anyone make reference to the very particular choreography provided by Jack Cole, expressly at Ginastera's wish, for the original production given first in Washington in 1967. In an interview Ginastera gave on Spanish television only five years or so before his untimely death, he spoke enthusiastically about Cole. Jack Cole was famous for his routines with Rita Hayworth and Marilyn Monroe amongst others. It was his work for the Broadway production of The Man of La Mancha that really made an impression on Ginastera and why he asked the president of the Opera Society of Washington to commission him to do the choreography for Bomarzo. Cole had never worked on an opera before and he was so entranced and fascinated by Bomarzo that he ultimately waived his fee and did his work out of pleasure and as a simple favour to Ginastera.

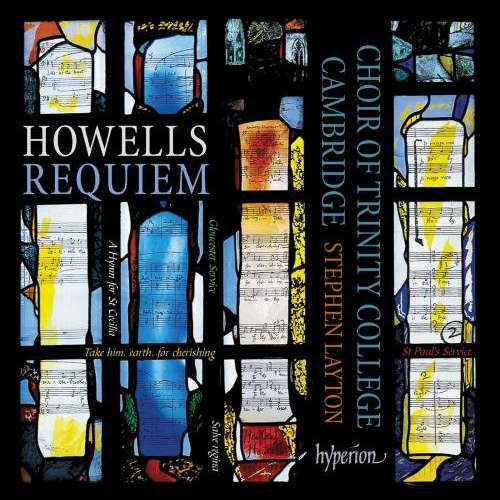

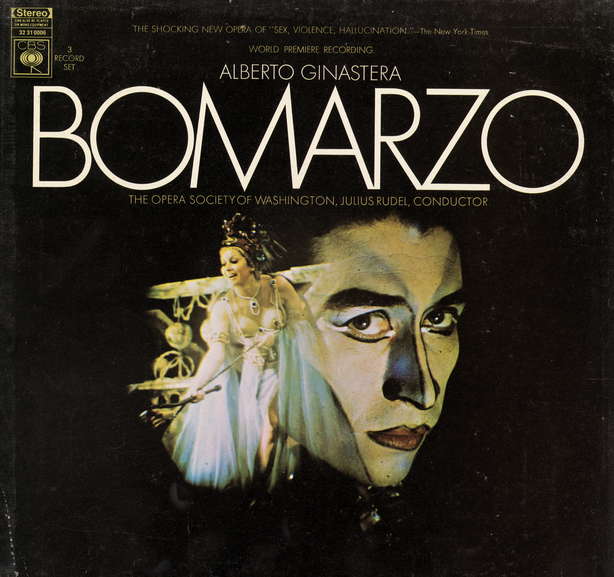

Likewise apart from some general comments few talk in depth about the single most extraordinary aspect of Ginastera's Bomarzo: the score. As an indication of just how astounding I think this score is, from the first time I heard an excerpt from the opening pages of the opera on the radio about twenty-five years ago, finding a complete recording of the piece became my life's single greatest ambition. Those responsible for the original production made a recording at the same time which was released as a triple LP box the following year. I searched and searched for this box but in vain until six years ago on the centenary of Ginastera's birth in 1916 Sony had the decency to finally release the original CBS recording on CD but I still dreamed about that original CBS box.

Ginastera: Bomarzo. © 1968 CBS Masterworks

Sex, violence, halluciantions, the synopsis I provided above. Trying to describe the inimitable sounds that Ginastera dragged out from within his most scintillating, surreal, sparkling, sumptuously seductive and superabundant musical imagination is a forlorn task. In 1967 there were many compositional methods and tools that were flavour of the month among lesser composers than Ginastera. But there is nothing dated or hackneyed about the unique soundworld of Bomarzo. Its power, subtlety and strangeness remain undimmed. Its hypnotic spell only increases with further listening. In all his music Ginastera deployed the entire orchestra like a magic wand but arguably never to quite the same bewitching extent as in Bomarzo. The orchestra is not much larger than what is required for a Mozart symphony. However on top of that is the extraordinary addition of seventy-three different percussion instruments. There is also a mandolin, a harpsichord and a viola d'amore. Added to this are orchestral clusters, a chorus vocalizing dozens of different languages simultaneously and that unforgettable hauntingly magical microtonal harp that accompanies the boy's starkly simple song. The sacred grove awaits.

Listen — Ginastera: Prelude (Bomarzo, Op 34) (extract)

℗ 2016 Sony Classics :

As a postlude to this piece, on my first post-COVID travel ban visit to Madrid last year, I went to the one and only specialised classical music CD shop in the entire four million strong city. It had changed location. When I entered, behind the desk was an employee I had never seen on previous occasions. When she greeted me it was clear that she was from Argentina. As we talked I noticed that on the wall beside her were placed, record collection style, various second hand LPs. The shop had never previously sold LPs except for the occasional gimmick reissue, so I asked if they were for sale. She told me they were and if I was feeling brave there were plenty more in the loft at the top of a small staircase behind her. Such an invitation was a proverbial red rag to a bull. So I disappeared up the stairs to find myself in a small space where the roof was no more than four feet above the floor. As I got to my knees and started to investigate I quickly realised that this was not another depressingly predictable collection of Spanish classical LPs. Within minutes I had pulled out a copy of Bomarzo, the CBS box, twenty-five years after its existence had entered my life. Not only that, it was an Argentinian pressing which I did not even know existed. The Duke of Bomarzo may not be immortal but he is alive and well. Sadly, when I checked a few days ago, the shop where I bought it no longer exists.

Copyright © 15 November 2022

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain

TWENTIETH CENTURY CLASSICAL MUSIC

ECHOES OF OBLIVION - FURTHER INFORMATION