- Countess of Harewood

- Sverre Valen

- Outhere Music France

- third century music

- minimalist music

- Hrachya Melikyan

- Johann Pachelbel

- Opera National de Paris

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

ASK ALICE: Weekly, from 2003 until 2016/17, Alice McVeigh took on the role of classical music's agony aunt to answer questions on a surprising variety of subjects.

ASK ALICE: Weekly, from 2003 until 2016/17, Alice McVeigh took on the role of classical music's agony aunt to answer questions on a surprising variety of subjects.

Horses for Courses

De gustibus non est disputandum is an old adage that may be useful for avoiding divorce proceedings when the in-laws come around for Christmas dinner but it is the death of musical criticism; which is the nature of our game here at Classical Music Daily. Thus long may we continue to ignore such advice. In a recent review on this site I read Allan Pettersson being described as Sweden's greatest composer of the twentieth century. As regards Pettersson's being Sweden's most famous or most popular twentieth century composer I might well be inclined to agree or certainly would see no reason to dispute the matter, but being the most popular or famous and being the greatest is a whole different Swedish kettle of fermented fish. Limiting myself to just his, more or less, contemporaries I can think of more than half-a-dozen of his musical compatriots whose compositional talents I rate above Pettersson's. They would be Gösta Nystroem, Hilding Rosenberg, Hans Holewa, Karl-Birger Blomdahl, Ingvar Lidholm, Åke Hermanson and the composer I wish to focus on this time: the brilliant Bengt Hambraeus.

Bengt Hambraeus (1928-2000)

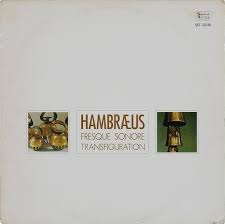

Owing to the miracle of music (in almost all of its multiple and varied forms) over the decades I have been fortunate enough on several occasions to have been exposed to, for want of a better term, I shall baptise with the moniker of - what by the high hand of holy Jesus am I listening to - transformative, unforgettable, unrepeatable experiences. One of the most intense of these I owe to a Swedish Society LP of two works by Hambraeus. When I first heard this record I knew nothing of or about Bengt Hambraeus which I have found is probably the best way to make one's first encounter with the music of any composer, free as you are from any preconceptions and prejudices.

Swedish Society Hambraeus LP

Speaking of encounters, in 1971 Hambraeus composed an orchestral piece titled Rencontres. The encounters the title refers to gives the lie to those who misguidedly believe that there is some kind of inherent implausibility in the idea of a composer who chooses to adopt modern compositional means and yet is saturated in and deeply influenced by music from his or her past; the erroneous notion that there is some kind of fundamental difference between what Bach, Beethoven, Bartók and Boulez were doing. There isn't. They all chose to scribble notes on paper with the intention of having these notes transformed into sound. Hambraeus' Rencontres despite its thoroughly original and modern sound is awash with echoes of Beethoven, Mahler, Wagner, Scriabin and others. This is not however some kind of postmodern pastiche or some way of poking fun at the past. Not at all. All these rich quotations are used for their purely musical potential in the creation of a piece that is wholly unique, wholly Hambraeus and wholly part of the ongoing tradition of Western classical music.

For Hambraeus his encounters with Bach were just as important and inspirational as those which he had with Varèse. Those with Buxtehude or Reger on a level with those with Webern. Indeed those with non-Western musical traditions were not of less importance to him than any of those he experienced with his own European musical inheritance. His profound, expert knowledge of medieval and renaissance music (indeed he was working on his PhD in Renaissance Music whilst attending the famous summer courses in Darmstadt in the 1950s) and his lifelong attachment to the organ were for him in no way a contradiction or an obstacle to his fascination with and implementation of the sound, texture and seemingly limitless possibilities of tape recording; the combination of live and recorded sound, electronically modified sounds, spatial effects in live performance, the live synchronisation of taped sounds which meant that in theory every performance of a piece could be utterly unique. All of these means, and more, were for Bengt Hambraeus of equal importance and relevance, and possessed equal justification and fascination as any more traditionally conceived and utilised compositional methods - all strings of equal importance to the composer's bow. The fact that many listeners, musicians or critics can not entertain or abide this reality says everything about them and their ideas about what music is or should be and nothing about the music nor the musicians who can entertain indeed thrive in such a reality.

The organ in Bjurbäck Church, Västergötland, Sweden

I was totally oblivious to all of this at the time but Fresque Sonore - my first encounter with his music - exemplified so many of these aspects of his thought and music making. It begins with his signature organ. Not the kind of consonant organ music I used to hear regularly as a child when I devotedly received the transubstantiated body of Jesus Christ but organ music nonetheless. I am not an organist, indeed I know very little about the instrument and the intricacies of its playing but I have always thought that its sonic possibilities are maybe unmatched by any other single instrument - a situation to which sadly few composers, to my knowledge, have really done justice. Hambraeus is one of the greatest exceptions in this regard.

Listen — Bengt Hambraeus: Fresque Sonore

(extract) ℗ 2014 Swedish Society :

After a few minutes of solo organ another of Hambraeus' favourite and most important instruments, or at least instrumental groups, makes it appearance namely percussion, in the shape of what I believe are bongos. Soon followed by another of the key components of this sonic adventure: a wordless soprano. Hambraeus chose to call this piece a fresco but to me it is more like a Persian rug, in that he created a vivid, polychromatic tapestry - one in which are interwoven so many disparate, colourful threads that enable the listener to embark on a genuine magic carpet ride.

Listen — Bengt Hambraeus: Fresque Sonore

(extract) ℗ 2014 Swedish Society :

A lattice of bells, flutes, gongs, brass, woman's voice and violin, all pre-recorded separately, filtered and mixed by the composer's caprice that can take you wherever your imagination wants to go. As we come into land, a harp swathed in distant gong and mixed with harpsichord sets the scene before a flute solo leads us not back to the organ console but to a last gentle gong vibrating into eternity.

Listen — Bengt Hambraeus: Fresque Sonore

(extract) ℗ 2014 Swedish Society :

I first listened to Fresque Sonore through headphones lying on my back on the floor. I don't know how long I lay there after the music had come to an end but I do remember the light fading as the earth spun and the day faded into night before I got up and decided to turn the record over. After such a transfiguring experience it was with a mix of trepidation and humorous serendipity that I realised that the piece on side B was called Transfiguration. I won't go into more details about this piece other than to say it is, I suppose, more conventional than Fresque Sonore but it lived up to its title and did not disappoint in the slightest. It was written in 1963 six years after Fresque Sonore and has more in common with other orchestral pieces of the time but nothing else quite sounds like Hambraeus.

Bengt Hambraeus the musician and the man stands for me as one of the greatest examples of a human being open to the limitless possibilities that life has to offer, especially so in the case of a creative artist - someone who refused to impose limits on himself, his interests, his inspirations or his creative ideas. When we live in a world formed for the majority by such provincial and parochial ideas of what constitutes music and/or culture in general, whilst on the other hand we have to contend with the abhorrent phenomenon of 'crossover' which disastrously attempts to meld two or more divergent traditions together in a way that utterly obliterates all their original, unique power and beauty and ultimately waters them down to an insipid, inoffensive, easily forgettable, mediocre muzak-like mush just so some capitalist can make millions peddling this nonsense as some kind of politically correct multiculturalism which makes prospective buyers think they are contributing to a good cause and being 'right-on' at the same time. In such a context I would instead advocate listening to the genuine multiculturalism of Bengt Hambraeus.

A long time ago T S Eliot warned about the menace of provincialism, specifically in the case of historical provincialism, in the sense that too many people perniciously view their lives and their world solely in the context of the present moment without any meaningful reference to the past. But what he said in that context I think is relevant here, in that if we are not to be far more open and Catholic in our ideas and tastes about what music is, we leave ourselves open to Eliot's diagnosis:

We can all, all the peoples on the globe be provincial together and those who are not content to be provincial can only become hermits.

Music can bewitch, can console, can exult, can excite, can cheer up, can confirm your most cherished beliefs and conform to your ideas about what music should be. However the idea that music can or should only be about these things is a menacing, prohibitive and ultimately impoverished one. In a world where the status quo falls some way short of utopia for most of the lifeforms that share this planet, if music is not allowed (indeed expected as with all art forms) to be viewed as an extraordinarily unique vehicle to challenge, criticise, discomfort, estrange, and transfigure by changing how you think and feel, as something that does not necessarily imply a suffocation of thinking for the benefit of the pure pleasure of mere feeling, then I would prefer to be one of Eliot's hermits ... preferably living among the puffins on Skellig Michael.

Puffins on the island of Skellig Michael, County Kerry, Ireland. Photo by Ewan McAndrew (CC BY-SA 4.0 creativecommons.org)

This feature copyright © 23 October 2022

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain

TWENTIETH CENTURY CLASSICAL MUSIC

ECHOES OF OBLIVION - FURTHER INFORMATION