VIDEO PODCAST: New Recordings - Find out about Adrian Williams, Andriy Lehki, African Pianism, Heinrich Schütz and Walter Arlen, and meet Stephen Sutton of Divine Art Recordings, conductor Kenneth Woods, composer Graham Williams and others.

VIDEO PODCAST: New Recordings - Find out about Adrian Williams, Andriy Lehki, African Pianism, Heinrich Schütz and Walter Arlen, and meet Stephen Sutton of Divine Art Recordings, conductor Kenneth Woods, composer Graham Williams and others.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. On Buoyant Form - Orchestral music by Andrew Downes, heard by Roderic Dunnett.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. On Buoyant Form - Orchestral music by Andrew Downes, heard by Roderic Dunnett.

All sponsored features >>

PROVOCATIVE THOUGHTS:

The late Patric Standford may have written these short pieces deliberately to provoke our feedback. If so, his success is reflected in the rich range of readers' comments appearing at the foot of most of the pages.

Seven Tuscan Nights

E andando nel sole che abbaglia

sentire con triste meraviglia

com'è tutta la vita e il suo travaglio

in questo seguitare una muraglia

che ha in cima cocci aguzzi di bottiglia. - Eugenio Montale

Feel with sad wonder

As you walk into the blinding sunlight

How all of life and its burdens is akin to

Making your way along the top of a wall

Covered in shards of broken glass. (my translation)

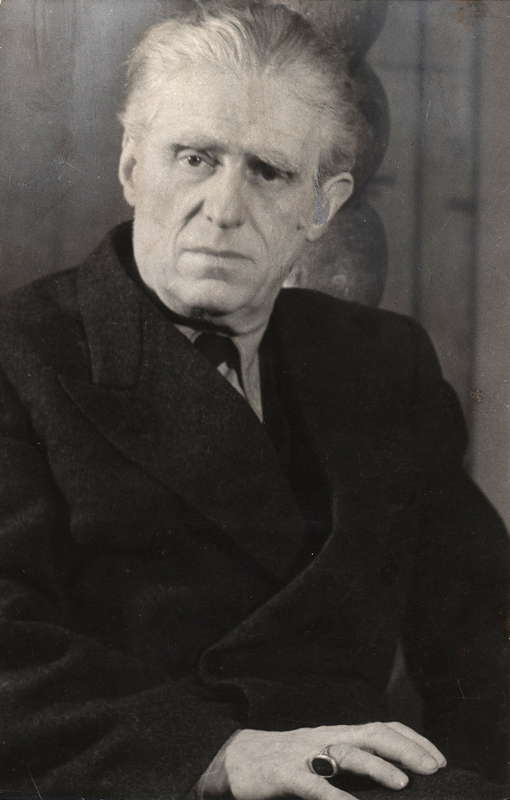

When Gian Francesco Malipiero was seventy years old he said the following: 'Potrei dire per il Torneo Notturno, secondo me, è la quintessenza di tutto ciò che ho sempre sperato di poter attuare dalle Sette canzoni in poi col "mio" teatro' (I could say that Torneo Notturno is, in my opinion, the quintessence of everything that I had always hoped to realise from the Sette Canzoni and thereafter with 'my' theatre.)

Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1973)

From this one can clearly see that both Sette Canzoni (seven songs) and Torneo Notturno - I can't think of a way to do justice to this title in English that does not sound or look erroneous or ugly or both so I will leave it as it is - were two works in the vast catalogue of Malipiero's oeuvre of the upmost importance to him. This being the case one is then forced to ask, for a composer who has been reasonably well-served by commercial recordings, why is it so difficult, and as regards Torneo Notturno absolutely impossible, to find any recording of these two masterpieces of twentieth century musical theatre?

The seven songs form the centerpiece of Malipiero's trilogy L'Orfeide, his unique take on the Orpheus myth, which this year is celebrating its centenary. In 1966, just five days before he died, Hermann Scherchen conducted a performance of L'Orfeide at La Pergola in Florence. Coincidentally a matter of months before Florence suffered a famously catastrophic flood when the Arno burst its banks one night in November that year, giving rise to the phenomenon of gli angeli del fango (the mud angels), a tonic to these post-Brexit, Eurosceptic times. That same Scherchen recording was released on CD thirty years later in 1996 on the Tahra label which I presume has long since been deleted. As far as I know this was its one and only commercial recording.

This may seem scant recognition for such an important piece but it is a veritable luxury in comparison with how Torneo Notturno has fared in the long history of recorded classical music. Not one single LP or CD recording whether live or in studio has ever been made. There may be some, presumably illegal, bootlegs of various RAI broadcasts floating around but that is as good as it gets for anyone like this writer who is totally enamoured of this little jewel.

The number seven clearly held some importance or at least some strong attraction for Malipiero. Along with Sette Canzoni his Pause del Silenzio, maybe his orchestral masterpiece, is subtitled seven symphonic expressions and Torneo Notturno consists of seven nocturnes.

Listen — Malipiero: I (Pause del Silenzio) (excerpt)

American Symphony Orchestra / Leon Botstein. ℗ 2010 American Symphony Orchestra :

Perhaps the use of seven disparate sections was a useful structural tool for Malipiero. He was famously averse to typical thematic development - something he always considered as classically German - and as someone loyal to the noble and lengthy tradition of Italian music and who lived close enough to the front line in the First World War to be able to hear the fighting, he always composed in a different indeed unique manner. He would present a theme, a melody or a motive and allow his intuition to take it where it wanted to go, for a given duration of time. When he felt he had exhausted its possibilities or had simply lost interest in playing around with it any longer, he would stop and start with a completely new, seemingly unrelated, motive. Thus, many of his pieces have a wonderful mosaic like texture. Listen to his wonderful first String Quartet or the aforementioned Pause del Silenzio for a perfect example of what I have attempted, very simplistically, to describe.

Listen — Malipiero: Rispetti e Strambotti - String Quartet No 1

℗ 2018 Celia Quartet (excerpt from St James Piccadilly, London performance) :

Although the seven nocturnes that make up Torneo Notturno stand alone in many ways they are more unified than is typical in many of Malipiero's compositions. This for me is what makes it one of his most cohesive, compact and ultimately convincing works. In a similar way to how a repeated figure on a lone trumpet unites the seven parts of Pause del Silenzio, the seven nocturnes share what is called Il canzone del tempo (the song of time) - a text and its accompanying music which is repeated in each part.

So what is this Torneo Notturno? That is a very good question and the difficulty I am going to have in endeavouring to answer it is in large part what gives this work so much of its mysterious charm and haunting power. To start off generally, it is a work that presents a vision of life and the human condition but does so in a very oblique way. It asks questions, demands reflection, presents situations but does not offer up any obvious answers or glib conclusions. In this sense it is a very good example of what Keats meant by negative capability. Its strangeness, uncertainty and disconcerting character is the quintessence of its power and hold over the listener and not in any way a weakness or a lack of inherent dramatic or musical quality.

Listen — Malipiero: Opening scene Torneo Notturno (excerpt)

Coro e Orchestra del Teatro dell'Opera di Roma / Ettore Gracis

℗ 1968 Teatro dell'Opera di Roma :

The work centres around two principal protagonists: Il Disperato (the desperate one) and Lo Spensierato (the carefree one). These two in common with the rest of the characters are presented as allegorical figures: they have no or very minimal psychological depth. Il Disperato spends all his time in a valley of tears wallowing in self-pity and bemoaning how unlucky and unloved he is and always has been. Lo Spensierato, the bane of Il Disperato, spends all his time taking full advantage of what every moment has to offer his selfish whims without any scruples whatsoever, thus leaving behind him a trail of jilted, distraught and even dead women. Lo Spensierato is the one who sings Il canzone del tempo in each nocturne. It is a song which sings of a topic which has been addressed by artists since the dawn of humanity: the fleeting nature of time, the illusion of permanence in a transient existence, the defining character that mortality has on the human condition. 'Chi ha tempo e tempo aspetta il tempo perde' (whoever has time and waits loses it).

Il Disperato spends the whole Torneo pursuing Lo Spensierato, attempting to prevent him from causing any more suffering to those around him, but he is constantly foiled and mocked in his vain attempts until the final scene. In a poetic sense therefore he spends the whole work desperately chasing a song which makes one ask, in such an allusive, allegorical work, is this Malipiero's metaphor for the dilemma of a composer or indeed a human being in general akin in a certain way to Schreker's Der Ferne Klang or Henry James' The Beast in the Jungle? That is for you to decide. Likewise I ask myself, are these two separate characters at all or two dispositions fighting a tug-o-war within one heart and soul? Even the most carpe diem devoted scoundrel can not remain forever ignorant of the fact that in a race against time there is only one winner. In the sixth part, the wonderfully titled Castello della Noia (Castle of Boredom), the character of the fool sings a song that leads one to think that maybe 'a tale told by an idiot signifying nothing' is not so very far from the vision of life that Malipiero wished to present in Torneo Notturno.

In the final scene the two protagonists find themselves sharing a prison cell. Il Disperato finally kills his sworn enemy and manages to steal his song with which he fools Lo Spensierato's last victim, the wife of a castellan, and thereby manages to effect his escape. But there is no escape. Who would be foolish enough to think anyone can escape themselves or the reality we are thrown into? It is also intriguing that the Castellan's wife was smitten by the song rather than the singer; an interesting reflection on the relationship between any creative artist and their creations. However, the masterstroke of the entire piece for me comes at the very end when Il Buttafuori (the bouncer) addresses us, the listeners or spectators. By doing so he dismantles the gulf separating us from the players - we are now no longer on the outside looking in but are ourselves all of us inside the torneo implicitly involved, compelled inescapably to live by the same laws and logic as the characters on the stage. Poor players strutting and fretting.

He leaves us in no doubt about the fate of Il Disperato. He says we may have thought that revenge and freedom have brought the desperate one peace and relief from his tortuous passions but think again he tells us, his torment continues 'ha ripreso su cammino senza meta' (he has taken up once again his endless path). Then comes for me the almost harrowing Non é finito (it's not over) as if to say to us this opera may be over but what it deals with is never over. It will be with you when you get home tonight, when you wake up tomorrow, next week, next year, forever, there is no escape. Non é finito. Finally we hear a foreboding march tapped out on a drum and Il Buttafuori asks us 'Do you hear?' Do you hear that funeral procession? It is life passing by, waving the banner of death.

Listen — Malipiero: Final scene Torneo Notturno (excerpt)

Coro e Orchestra del Teatro dell'Opera di Roma / Ettore Gracis

℗ 1968 Teatro dell'Opera di Roma :

I have talked a fair bit about the text of this piece but of course it would be nothing more than a Renaissance poem were it not for the uniquely haunting and evocative harmonic world of Malipiero's extraordinary music. Torneo Notturno was composed in 1929 when all of Malipiero's influences and compositional methods and signature sounds had coalesced into something uniquely his own. I would like to dedicate this piece to the memory of the late Michael Edgar Oliver (MEO) who died twenty years ago this year far too young. It was through one of Michael's radio broadcasts that I was first made aware of Gian Francesco Malipiero and Torneo Notturno specifically. Just one of the many amazing discoveries whether through his radio programmes or his writing in Gramophone magazine that I owe to him. The last word the bouncer says to us in Torneo Notturno before the low brass and bass drum slide into silence is ascolta (listen).

Copyright © 26 August 2022

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain

TWENTIETH CENTURY CLASSICAL MUSIC

ECHOES OF OBLIVION - FURTHER INFORMATION