DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

Universality of Emotion

ONA JARMALAVIČIŪTĖ talks to

American composer Rain Worthington

Self-taught American composer Rain Worthington is reaching international acclaim through her unique view of the American style of music. Critics compare her creative work to a walk in a familiar, yet very different park, expressing admiration for her use of musical influences from world music, minimalism and romanticism. The music of Rain Worthington is packed with emotion and speaks directly to listeners' senses because she has always followed her own musical instincts. Her pieces, awarded with grants from ASCAP, the American Music Center and the American Composers Forum, have been performed worldwide with premieres in Tokyo, at Oxford University, and at the Delhi Music Society. I recently conducted this Q and A session with the composer, where we discussed creativity, the purpose behind her work and her state of mind while writing music.

Rain Worthington. Photo © 2018 Mark Berger

Ona Jarmalavičiūtė: You are a self-taught composer. How did you first get in contact with music and music making?

Rain Worthington: It is interesting how certain moments in our lives weave their way into the subconscious to emerge later in life. There were several situations in my early life that left musical imprints on me. The first was the piano at my grandparents' house where I lived during my earliest childhood years. I would wake up and go 'play' the piano; I loved the sounds of the notes and making up patterns. Also, during this time I saw the Disney animation film Fantasia which made a lasting impression upon me, especially the music of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring. However, the real impetus for beginning to compose came when I was staying at a friend's house with a grand piano. As I had some time in the house alone, I sat down at the piano one evening and was taken back to my childhood and once again started to make up little patterns and sequences. The piano is uniquely accessible among instruments in that a complete novice can strike the keys and instantly make a lovely tone, without needing any technique to get that beautiful sound. I just fell in love with the sound of the piano and creating set pieces. The accessibility of the instrument gave me an immediate gateway into composition! When I returned to my loft in Boston, I decided I wanted to continue creating musical patterns and purchased a lovely old upright piano. I brought this piano with me when I moved to New York City.

In New York City I moved into a raw loft in the neighborhood of Soho which had been a somewhat dormant warehouse district between Houston and Canal Streets in NYC. This was in the mid-seventies before Soho became commercialized. Here I discovered and became immersed in an atmosphere of tremendous creative energy and genuine support among artists and musicians. It was a vibrant scene of artistic expression and experimentation. Music concerts, dance performances, painting and sculpture exhibitions were happening all the time. Often events were staged in fellow artists' living loft spaces. So, when friends encouraged me to perform my piano pieces, composer Charlemagne Palestine offered me the use of his loft space and his beautiful Bosendorfer piano to present a first concert of my solo piano music. At this time, I had not yet learned music notation, so I played my pieces from memory. I performed two sets of concerts at Charlemagne's loft, and subsequent concerts at the nascent music venues in downtown Manhattan, such as The Kitchen and The Ear Inn.

OJ: What would you call your ‘teachers' when you first started composing?

RW: As I did not pursue a traditional path of study, academic institutions, professors and instrumental training did not play a significant role in my development as a composer. I was lucky to have discovered my love of the piano and creating music simply through the immediate accessibility of the instrument - exploring and following my own music through the sounds of the piano. But the real catalyst for performing my pieces publicly and beginning to think of myself as a composer came from the excitement of creativity that was happening in the mid-seventies. The atmosphere was creatively charged, mutually supportive and artistically nurturing. This was the environment where I was first introduced to the contemporary music scene and where I began to conceive of the possibility of becoming a composer.

OJ: Your creation is described as world music, minimalism and romanticism. How would you describe your music in terms of genre?

RW: It seems to be part of human nature to want to name things to bring a sense of order and understanding to the world. In contrast, creative artists often want their work to be seen as unique, so tend to resist categorization of their art. However, as contemporary music is new music, it's useful to apply descriptors that offer listeners accessible windows into the music. So, beyond the generalized genre of 'contemporary classical', which already encompasses a broad spectrum of styles of music, I list world music, minimalism and romanticism as types of music that have been influences in my life.

World music has opened me to other modes of musical expression - rhythms, instrumental timbres, musical structures and modalities. The African, Arabic and Latin polyrhythms, the timbres of gamelan, Tibetan bowls, Mid-Eastern and Asian flutes and string instruments, the call and response of chants and field songs, the microtones of Middle Eastern modes have all seeped into my creative subconscious wellspring. I love the sounds of these musical cultures - the music seems to reside deep within me, and always has from an early age. Duke Ellington's Caravan was one of the first songs I remember loving as a child.

The minimalist movement was vibrant and all around me when I first moved to New York City. And, importantly, as someone who had come to music intuitively, the minimalist aesthetic provided an opening and acceptance of a certain level of naiveté, and the support of fellow musicians provided accessible performance opportunities. As for romanticism, all I can say is that it has always been an elemental part of my nature.

At times one hears the influence of world music in moments of percussion, at other times a given turn of phrase in melody is deliberately repeated for emphasis, mining a bit the world of minimalism. But overall this is the work of an eclectic, sui-generis musical artist who walks to the beat of her own romantic heart and outside the parameters of contemporary music.

- Rafael de Acha, rafaelmusicnotes.com

OJ: Do you strive to be unique in your creative work?

RW: Instead of striving to be 'unique' in my musical expression, I strive to be true to my emotional experience of life. I believe one of the highest goals of life is to pursue a true expression of your life spirit and personal commitment to your sense of purpose in life. For me, channeling an expression of life through music seems to be my truest path - with the hope that the interconnection through music will have some positive effect in the world toward engendering compassion, acceptance and understanding.

OJ: What do you value the most in your music?

RW: What I believe is the most important aspect of my music is the ability to tap into a kind of universality of emotion. The capacity of instrumental music to connect deeply to communicate emotions that are universal, without the specificity of language, is fascinating and mysterious to me. I explored this phenomenon a bit in an article entitled The Communicative Mystery of Instrumental Music that was published in Sonograma Magazine.

OJ: What kind of impact do you want to have on the listener?

RW: I believe very strongly in the universality of emotions and the shared pathways of human connections. Emotions are our opportunities to recognize the similarities between us, and to understand that we share more common experiences and values than things that are divisive. I like to believe the emotions I tap into through my music will resonate a commonality of understanding with listeners, so that we will have shared an experience of connectivity through a musical journey.

OJ: Define inspiration - does it exist?

RW: Yes, I believe that inspiration could be defined as a stimulus for positive or creative action. Inspirations arise from many different sources of my experience of life - tapping into emotional currents that underscore every moment of living, whether perceived consciously or subconsciously. As a composer I want to be aware and openly receptive to those currents and try to translate some of those emotional complexities into music that touches the heart and is accessible, nuanced, insightful and transporting.

OJ: How do you usually create an idea of a new piece?

RW: Many different things have sparked inspirations for a new composition. The distant beeping sounds of city trucks backing up in the late night became a source point for the opening of the nocturne Yet Still Night. As music journalist Kyle Gann described the music: 'You first think this is a lullaby, rocking back and forth between D-flat and B-flat in quarter notes that wander around the orchestra. But this is an urban lullaby, and the nocturnal world intrudes in growing chromatic lines and thickening textures.'

The residual year-end emotions and edgy impatience to move forward inspired Still Motion - a cycle for orchestra. A dream of a careening bike ride through dense night fog with no visibility and no brakes(!) inspired the music of Fast Through Dark Winds that turned out to be a metaphorical expression of my emotional struggle in coping with my mother's decline into profound dementia.

And there are lighter or more playful sources of inspiration as in my miniature Frost Vapors, which was written in response to violinist Eva Ingolf's call for short works on a theme of Iceland as a land of 'mystery and trolls'. Another lighter side is the give and take of love relationships expressed in Jilted Tango.

OJ: How do you transform an abstract idea into a material piece of music?

RW: How the initial seed of an inspiration transforms into a musical composition is a wonderfully mysterious and awe-inspiring process. I do not approach composition theoretically or architecturally, but rather the work develops, most often, in a 'through-composed' process in which one fragment of music leads to another simply through an emotional subconscious sense of logic or even musical playfulness. It is important to me that the piece is a journey that moves through time in a way that feels true and makes emotional sense.

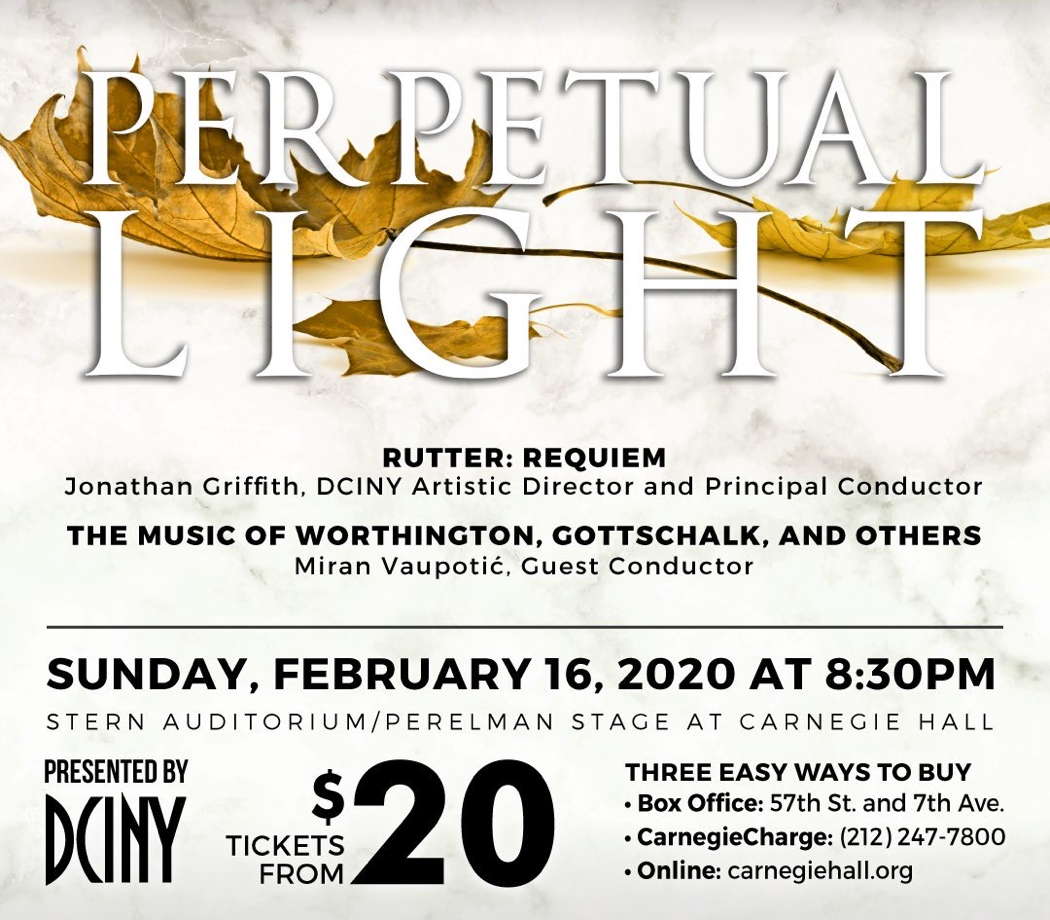

Publicity for a February 2020 concert featuring Rain Worthington's music

OJ: How do you listen to music?

RW: I listen to and enjoy all kinds of music from world music to pop dance music to jazz. My listening habits depend on whether I am actively working on a new piece, or whether I am in a more social setting or have time when I can really hear and absorb the music. I am most disheartened that music has become an omnipresent background for every public environment. I am very wary that this level of constant aural saturation of 'unintentional' listening will begin to numb people to the potential of transformative deeper 'intentional' listening. I feel it is important to stay in touch with music that delves into emotional complexities that are not easily categorized.

When I have the time to engage in focused listening, the music that I am drawn to is that which has the power to touch me emotionally and resonate most deeply into my soul. I was recently asked by radio music host Dominique Johnson to curate a playlist of my own works and those of other composers that could reflect the idea of what would be my 'Classical DNA'. It was an interesting concept to consider and quite a process of reflection.

The works of my own that I selected were some that have held special importance - sometimes at pivotal points in my life. These included two early piano pieces Conversation Before the Rain and Part 1 from the North Moore Street Loft-2nd Concert; a violin duet Night Stream; and the orchestral works Shredding Glass, Fast Through Dark Winds, Tracing a Dream, Of Time Remembered and In Passages. The musical selections from works by past composers are ones that have been indelibly imprinted on my heart and soul ... music that has lingered in my memory, music that comes back to me - that will start playing in my mind. These included two piano works by Erik Satie: 3 Gymnopedies: No 1 and 3 Morceaux en forme de poire: No 1 and orchestral excerpts from Stravinsky: The Firebird Suite: Lullaby, The Rite of Spring: Part One: Adoration of the Earth, and Petrushka: Second Scene: 1. Petrushka's Cell, and from Debussy: Nocturnes: Nuages.

Additionally, I selected works by two contemporary women composers, Hilary Tann and Marga Richter, that I admire and with whom I feel I share some similar musical sensibilities. Those works include Hilary Tann's Shakkei: 1. Slow and spacious and Marga Richter's String Quartet No 3: Movement 1, and her vocal work Sarah Do Not Mourn Me Dead.

OJ: Were you ever discouraged in your professional path of creativity?

RW: A roller coaster of highs and lows between confidence and self-doubt is absolutely my experience of life as a creative artist. It is almost a constant component of my life and continually a tumultuous ride. The only way I can work through it is to focus on centering myself in whatever way that works - I use yoga, exercise or some physical activity in nature to help keep me centered. One of the most discouraging states of mind that a composer, or any creative artist can sink into is that of comparing one's work to others' works. It can become a deadening cycle of 'compare and despair' and block all creative impulses. Creativity is not a competition. I continually remind myself of this as I receive notices that my works were not among scores selected or prizes awarded. Likewise, this a good reminder to keep in mind when pieces are chosen or receive recognition. Whether a rejection or acceptance, the process of creativity cannot become a competitive pursuit. Generosity and expansiveness of spirit are essential for staying positive and productive. The recognition and successes of individual composers can have a ripple effect to promote awareness of contemporary classical music and can benefit all composers working in the field.

OJ: Do you think that creativity is part of human nature, or is it something that must be nurtured and learned?

RW: I think creativity is a healthy and elemental part of human nature. I believe the world and societies would be better and more humane if creativity was more valued and actively nurtured. The value of the arts and music has been documented in countless studies. The research has shown repeatedly that opportunities for creative expression through art and music can heighten mental functions, expand cognitive abilities in many areas, and can reduce anxiety and aggressive behaviors. Yet, ironically, arts and music programs are among the first components to be cut in educational budget decisions. Quite to the contrary, I feel that nurturing artistic expression and creative thinking in problem solving should be among the most essential components in any educational system.

OJ: How much of your own life is reflected in your work?

RW: Most of my life is reflected in my music. My life experiences and the subconscious emotional meanings are the source point of all my compositions. While the initial inspiration for a composition may be sparked by a specific sound pattern or rhythm from everyday life, the music then becomes a journey through which I travel, touching upon a deeper emotionality which informs the music. In this way, I never see the finished product before I start. It is often only during the composing process that the emotional meaning of the music becomes clear to me. It's similar to a story that is being told in first person present tense where I, as the listener, only discover what happens as the music/story progresses. Thus, titles for most of my works come after the piece is in progress or more often when it has been finished.

OJ: Could you describe your state of mind when you are creating?

RW: Trying to describe one's state of mind when creating is something that has been a source of ineffable mystery with attempts at descriptions ranging from 'being in the zone' or 'channeling' or serving a 'conduit for the inspiration'. I feel all these are accurate in the sense that it is a state-of-mind that is more accurately 'out-of-mind', transported beyond the conscious mind. All people have experienced this state of being and have felt transported out of themselves and the confines of perception through everyday senses, at least in the very similar way that the sense perceptions fade as we drift into sleep and we enter a different level of consciousness and logic. We are all essentially, if unwittingly, creative artists, as our subconscious fashions our dreams. Whereas those who pursue the arts with intention are attempting to express the subconscious levels of emotional logic in ways that communicate the commonality between us all.

Rain Worthington. Photo © Lana Ortiz Photography

OJ: If you could change one aspect of our society through your work, what would it be?

RW: To inspire understanding, compassion, and respect for the connectedness of all life on this planet. I believe in the profound oneness of all, and the significance and responsibility for the consequences of all actions.

OJ: Thank you for the conversation!

Copyright © 9 December 2019

Ona Jarmalavičiūtė,

Vilnius, Lithuania

FURTHER INFORMATION: RAIN WORTHINGTON