DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

ARTICLES BEING VIEWED NOW:

- Régine Crespin

- Hector Berlioz

- Ruth Railton

- Marián Varga

- Profile. A Very Positive Conductor - Paul Bodine talks to Los Angeles Opera's Music Director Designate, Domingo Hindoyan

- Valery Gergiev

- Roger Quilter

- Cornelius H Edskes

- Don Hazelwood

- wind bands

- Georg Anton Benda

- Leivi

- David Walter

An Early Maturity

GEORGE COLERICK spotlights 1823,

a critical year in the career of Franz Schubert

Schubert was a Viennese boy, the first great composer to be without a patron, in that sense an amateur, a poor music teacher. A bachelor, even his emotional life was impoverished though exaggerated through legend, and his health was always poor. 1823 was to be a critical year in his tragically short career. Aged twenty-six, behind him was his youth when he had shown such precocious talent for song-writing. If that had come easy to him, symphonic writing is for all a challenge involving a kind of apprenticeship, of which many composers later destroy the evidence. Spontaneous and unpretentious, such a thought would not have occurred to Schubert, and his first six symphonies exist as his 'juvenilia' but as such, a considerable achievement. They had been written much under the influence of Joseph Haydn who had died in 1809.

By 1823, Schubert's early maturity had been advanced by a degree of suffering, and the new awareness that he had few years left. Not concerned with material things, he was disordered and much of his work was lost or mislaid. That year, he spent some time in hospital under treatment for an incurable venereal disease. Though the chronology can never be certain, he completed by that year two movements of what one day would be world famous as his Unfinished Symphony. In the structure most suited to important public statements, he had suddenly shown maturity and musical individuality. It makes interesting contrast with his Fifth Symphony, quite Classical, written seven years earlier but with Schubert's personality.

Detail from an 1875 oil painting of Franz Schubert

(1797-1828) by Austrian painter and draughtsman

Wilhelm August Rieder (1796-1880),

based on an 1825 watercolour

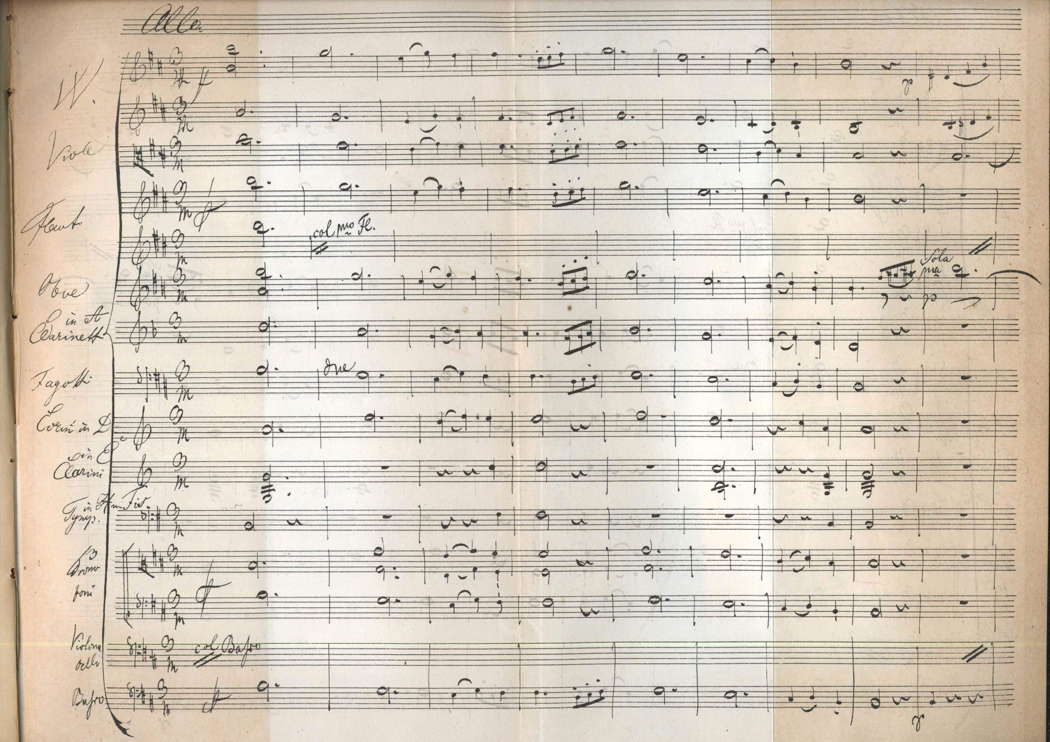

The missing two movements of the Unfinished Symphony have been one of the largest puzzles in musical history. Did he stop work on it around the time of his hospital stay? This cannot explain why he did not finish several other works. Perhaps he realised it could stand best as it was; even Brahms who was strict about symphonic form thought so. More likely, he felt the urgency to express more rapidly the many ideas within him. He had just one more such work and most ambitious in scope, the Ninth. As for the Unfinished, part of a third movement exists and allegedly the fourth appeared some months later as the first entr'acte in incidental music to the play, Rosamunde. It was sometimes played as a substitute with the symphony though some have argued that it lacks the nature of a finale. Its status remains in question.

Facsimile of the opening of the incomplete third movement of Schubert's Symphony No 8 in B minor - the Unfinished

With the briefest of introductions, the apprehensive first subject builds up to an impassioned climax, the relief coming in the form of a flowing melody which has become one of the best loved in all symphonies. Listeners might relate the restrained sense of menace to Schubert's condition in 1823. Thinking partly of his emotive use of the cello section, Julius Harrison writes of skill in imposing the 'hushed effect':

Not only were his melodies scattered about the instruments with deep feeling for their characteristic tone colours, but the actual range of dynamics was enlarged.

The following movement maintains a similar pace, more serene but having an affinity in a work noted for its darker harmonies. This Unfinished Symphony is the first great orchestral work in today's repertoire by a young composer breaking away from the Classical style. The Rosamunde music also from 1823 was its accomplice, deservedly sharing its popularity. It was composed for an inferior play Rosamunde which disappeared after a few performances. In the event that was hardly a loss.

Its now famous overture was written for an opera, then switched. It broke away from the fashionable Rossini style of dramatic contrasts in tone and pace, and has subtle changes in key and harmony. That also applies to the ten other movements he wrote, an exceptionally tuneful score not specially tied to the story but broadly suiting a domestic comedy. Neither a descriptive nor dramatic approach was necessary and the Rosamunde music stands now well on its own as a concert suite. Apart from the two concluding movements, the first a light chorus, there is often a wistful note touched by the clarinets in their middle range, and in a song, unusually for contralto voice. Benign influences are felt in two choruses representing the outer world and nature. The carefree finale has a rare trotting rhythm and was known as the 'Russian air'. That and a plaintive slow movement, have become especially familiar Schubert, and he used them both for other works. Several 'musicals' were once made about his life and work, often as a pastiche, with the Rosamunde music prominent.

To German Romantics around 1820, the term 'wanderer' was associated with personal freedom, escaping conventional responsibilities, communing with nature like by Byron and Shelley. In an 1816 song with this title, Schubert interpreted it more in the sense of an outsider, an unfortunate one, as he saw himself despite his enviable band of musical companions. The song was in 1823 placed with a set of variations in the slow movement of the Wanderer Fantasy. This work was shaped like a sonata but thematically linked over three movements. The significance of this was taken up years later and developed by Franz Liszt.

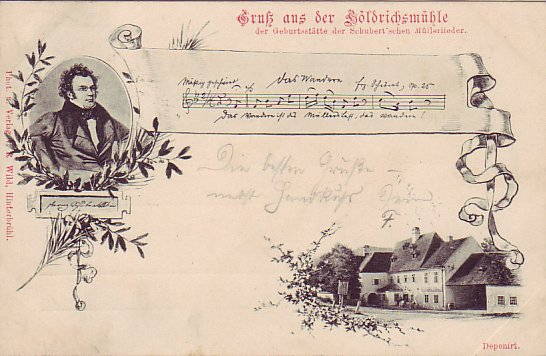

Song and operatic aria were quite distinct by the time of Schubert. He perfected the German song, the Lied, a great lyrical form essentially intimate, whereas though he wrote many arias, he failed in opera, which is essentially dramatic. Even so, he had a facility for interpreting texts by the greatest writers such as Goethe or average ones, his muse fired more by ideas than the words. In 1823, his choice was Die schöne Müllerin (The fair Maid of the Mill), and to a modest text he wrote a great song cycle on the ancient theme of unrequited love. It was entirely a plaint by the youth, the girl seemingly uninvolved at any time. Her indifference is indicated in the eighth of the twenty songs; her later interest in a young hunter, dressed in fashionable green, causes jealousy. The growing despondency of the young man is reflected in music near in feeling to its sequel Winterreise (Winter Journey), which sinks towards despair with the same character considering suicide.

Die schöne Müllerin is a lover's narration, drawing in literary clichés of that early Romantic era; he addresses and is consoled by the brook which powers the mill. The music enhances a simple story perfectly and three songs are specially well known.

A postcard from circa 1899 depicting Franz Schubert, the first line of his song 'Das Wandern' (which begins Die schöne Müllerin) and the Höldrichsmühle inn, Hinterbrühl, Lower Austria

The opening two overflow with youthful confidence, and the piano brings on the excitement of anticipation in the seventh, Ungeduld (Impatience), with the work's most familiar phrase, in one translation:

I'd like to carve your name in every tree.

The Schubert memorial at

Göttweiger Hof Spiegelgasse 2, Vienna, Austria,

with the inscription 'Franz Schubert lived in this house

1822-23 with his friend Franz von Schober and created

here, among other works, the B minor Symphony'.

Photo: 2012 Schubertbund/Creative Commons

Schubert had barely five more years to live: very prolific years considering his health, and including several masterpieces, to become one of the greatest and most influential of European composers.

Copyright © 19 November 2019

George Colerick,

London, UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: FRANZ SCHUBERT