- Paul Dean

- Parlophone Records

- Ingignero

- Donizetti: Anna Bolena

- Zydeco

- Bliss: Metamorphic Variations

- Giovanni Bottesini

- Mary Bevan

VIDEO PODCAST: James Ross and Eric Fraad discuss Streaming, Downloads and CDs with Maria Nockin, Mary Mogil, David Arditti, Gerald Fenech, John Daleiden, John Dante Prevedini, Lucas Ball and Stephen Francis Vasta.

VIDEO PODCAST: James Ross and Eric Fraad discuss Streaming, Downloads and CDs with Maria Nockin, Mary Mogil, David Arditti, Gerald Fenech, John Daleiden, John Dante Prevedini, Lucas Ball and Stephen Francis Vasta.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

A Silver Age

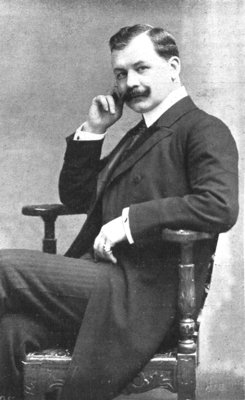

GEORGE COLERICK writes about Franz Lehár,

probably the greatest twentieth century

composer of operettas

It is difficult to find a clear-cut illustration of the difference between opera and operetta in the works of a single composer. An exception is Franz Lehár (1870-1948) who set out as an opera composer with Kukuschka (1896). It gave little suggestion that Lehár would become probably the greatest of twentieth century operetta composers.

Kukuschka, later revised and now recorded under the title Tatyana, has the theme of exile to Siberia, with two lovers dying together. It is a tragedy which has a similar shape to that of Manon Lescaut, though the lovers are more admirable. Lehár strongly approved that recent opera by Puccini and they developed a mutual respect and lasting friendship. Their main themes were of love affairs tending to the tragic, music rising to similar levels of intensity. They moved in slightly different directions, but they are perhaps equally regarded among Europe's greatest composers, and certainly most popular.

Franz Lehár in 1906, by Austrian photographer Ludwig Gutmann (1869-1943)

Lehár's operatic model was Slavonic rather than Italian, and much of Kukuschka's appeal came through his feel for Russian melody. The opera was very well received initially, but its subsequent neglect was so disappointing that Lehár decided against a second one. Instead, he was impelled towards the most fashionable genre of that time, operetta, reaching to some thirty stage titles. Posterity does not regret this. At least one half are available now in complete recordings, mainly in German.

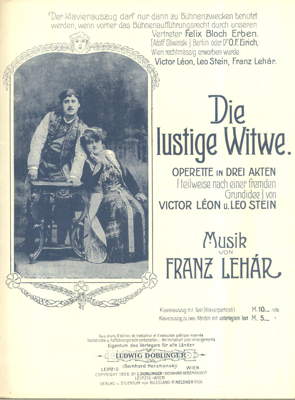

He was active when operetta stood at its final commercial peak over four decades. For some years after 1905, he would have been one of the few best known composers in the world because of the unprecedented popularity of one stage musical, The Merry Widow. Its world impact was immensely greater than any other one in the years before broadcasting. Today, for colour, melodic and rhythmic vitality it remains unsurpassed.

Lehár was born in the mixed Slavonic-Hungarian community of what is now Slovakia. As a bandmaster's son then soldier-musician, he spent periods in numerous parts of the polyglot Austro-Hungarian Empire, and became multi-lingual, a talent often associated with the Jews, of which he was not one. He acquired strong feeling for the music heard in the distinct parts of the Empire: German, Hungarian, Slavonic, Romanian, Italian. Yet as an ethnic Hungarian, he wrote at least one operatic melody, I hear a Cimbalom, so popular with gipsy ensembles that it is widely assumed to be a folk song.

The ability to absorb so many idioms, and the excitement he brought to them, distinguish him as a composer. Unlike today when the performance of musicals in the world's leading capitals is hampered by near-monopolistic conditions, in Lehár's productive years there was the strongest competition. Hundreds of musicals were good enough to have a lavish production, and the best would come out on top. They might have well over twenty excellent songs each, rather more than expected in our modern stage works. His successes ensured rapid wealth, but he was modest about this because he had artistic integrity and priorities.

The creation of great classical operettas, the Golden Age, comic and satirical, had virtually ended by 1900 with the death of its most famous names. At first The Merry Widow was thought to continue in the mocking style of Johann Strauss' Fledermaus. The ruler of the actual Montenegro complained that he was being sent up in the plot about a certain Pontevedro. The world might assume from it that Montenegro was a corrupt, tin-pot state like Monte Carlo!

Louis Treumann and Mizzi Günther on the title page of a 1906 piano vocal score of Lehár's Die Lustige Witwe (The Merry Widow)

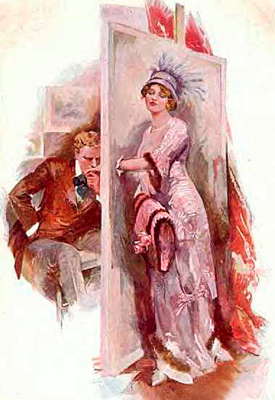

The Merry Widow was quickly followed by another prodigious success, The Count of Luxembourg, which ridiculed marriages arranged for aristocracies. Even so, Lehár asserted he was not in the long run interested in satire or writing 'funny music'. He intended to express great passions, ennobling ordinary people through the power of love, as his biographer Bernard Grun stated.

Drawing of Bertram Wallis and Lily Elsie in a scene from The Count of Luxembourg in London, 1911

Gipsy Love was a fine example, and it was a rare opportunity to present his native music idiom in its most sophisticated form. Decades later, he rewrote this full-bloodied music as an opera, ill-fated to be premiered during the bombardment of Budapest in 1944.

Lehár working in his flat in Theobaldgasse, Vienna in 1912, by Austrian photographer Charles Scolik (1854-1928)

After the 1914-18 war, he introduced the new dance rhythms into his scores, notably tangos and foxtrots, much reducing the waltz element. He also composed a complete Act as a much extended love duet, judged by some as deliberate Wagnerism. He refused suggestions it be altered to stop criticism. Yet there was a complete revision in 1930 as How fair the World, a work which avoided the sad endings of his four previous ones, though their tragi-comic vein was said by many critics to be his finest.

These had started in 1925 with Paganini, his twentieth stage work. Paganini had been a notorious exhibitionist, not too appealing when separated from his famed violins, and the kind of 'celebrity' no woman should become emotionally involved with. Napoleon's habit of placing his siblings to exercise power in his outlying Empire resulted in his younger sister Elisa being sent to an Italian puppet-state, Lucca. There she languished, married to the Prince who was having an affair with his opera's lead soprano, Bella. The historic accuracy of the events need not concern us; Lehár recognised a most suitable script, and arranged for the experienced Otto Jenbach to provide lyrics.

Lehár expressed powerful emotion without sentimentality, and he succeeded in avoiding romantically escapist plots so familiar in lesser works. In Paganini and the three following ones, each heroine is stoical as she renounces for honourable reasons her lover. This always occurs in the third Act, the first two being concerned with seduction, pleasure and intrigue. The operas were set in Italy, Russia, Germany and China, and to an extraordinary degree, Lehár's inspiration matched the need for local musical colour. There has since been no comparable sequence to rival them.

Lehár used none of Paganini's many compositions. As a violinist he wanted to assimilate something of the man's spirit before composing virtuoso passages for the first two Acts. Elisa had despaired of the freedom to find pure love, and she reveals her nature in a passionate aria, having concluded that Paganini is worth sinning for.

Her husband the Prince does not want him at Lucca, especially as he is alleged to have killed someone over a woman in a duel. When she threatens to expose the Prince's liaison with the soprano, he has to turn a blind eye, so for six months Paganini will be employed as music director. That is more than enough time for his affair with her to progress, seduction assisted by his composing a song for her. Yet it is not long before he desires Bella, so she in turn receives the dedication. His carefree attitudes are reflected in one of the most male chauvinistic songs to have gained world-wide popularity:

Girls are made to love and kiss. And who am I to interfere with this?

Lehár did not drop the Harlequinade tradition that there should be at least one inadequate clown in a sub-plot. In return for money favours, Paganini tells the Mayor the secret of his skills in winning women's affections. When the Mayor tries it on with more than one lady, he gets a slapped face; but does have the consolation of a song in waltz rhythm.

Paganini has gambled away his Stradivarius, but the news of his scandalous behaviour has reached Paris, and Napoleon sends a general to arrest him. He flees to the frontier, hoping that smugglers will get him out. Elisa is resolved to losing him, though she and Bella follow him until in a poignant finale for two women, he bids a cool farewell.

During the productive years, some forty, Lehár reduced the dance element in his stage works in favour of the dramatic. Yet with operetta committed to dance rhythms, he includes them effectively in his songs, such as in Bella's final aria, Seductive Love. It has a tango rhythm, but interspersed with a vigorous Italian strain from the chorus.

Lehár was specially proud of the eight-note motif, subtly varied, heard in the terse prelude, again when Paganini and Elisa first feel mutual attraction, dreamlike, 'ennobling', the musical climax held back until her explicit decision to be his lover. He responds with the motif, In your eyes I read, leading to an ecstatic duet. This is later complemented by another, Love, you Heaven on Earth, the equal of the even more popular No-one loves you as I do. It was written at the last moment to replace a melody considered too difficult for the soloists; because of its easy vocal range (tessitura), any enthusiasts might try it. Elisa's possessiveness in Act II is answered with a radiant Italianate aria:

She: You did not come to me last night. Were you with another?

He: Yes, I was with another. I was all evening with a love offering. I was composing it for you.

The premiere in Vienna failed because of the production, but the work was saved in Berlin by the arrival of one of the greatest inter-war tenors, Richard Tauber. A heavily-built man, his appearance was the opposite of the skeletal Paganini and this upset London audiences years later when C B Cochrane brought the work to the Lyceum. Yet Tauber had a voice to conquer all, and as a high tenor he was equally at home with Mozart and Lehár, whose delicate serenade from Frasquita (1923) he had already graced. A distinguished musical partnership grew up between the two men.

By 1925, Berlin was starting its greatest if brief period of creative musical theatre, and Lehár decided to place it at the centre of his plans. He produced those next three works successfully at its Metropol Theatre, home of operetta, with Tauber and some of Germany's finest light sopranos. Girls are made to love and kiss came to be known as the Tauber song, one of seven so-called over the years. Tsarevitch begins in Russia but the story moves to Italy in the third Act, and his Volga-Lied was probably his most nostalgic song. Fredericka was the nearest of all to tragic opera, with Maiden, my Maiden as the Tauber song.

One song not superior to many others he composed achieved disproportionate fame world-wide. You are my Heart's Delight has suffered from over-popularity, which must have annoyed Lehár. It came from the fourth work, Land of Smiles (1929), with its exquisite Chinese flavours.

Bernard Grun writes of Maiden, my Maiden:

It is the great main theme of the work, slowly dawning, constantly growing ... first as a flute solo, then as a contrapuntal decoration on the love motif in the prelude; and the moment the curtain rises, in violin octaves to distant organ accompaniment. In the first Act finale, it breaks through in its full glory.

But he cannot say as much for the other six Tauber songs:

They have in common the free, grand melody, vocal forcefulness, sonorous effect. Yet for all their brilliance and power, they fail from the viewpoint of musical drama through their dangerous transfer of weight in favour of the singing star. The action suddenly breaks off, the actor becomes a soloist, the interest of the audience turns away from the dramatic action to the song. This tendency did not stop at Tauber; it was reproduced by his imitators, who appeared everywhere, often an annoying part of a cliché. Lehár recognised this and tried to get rid of the habit; but in vain.

He would be appalled at the much increased cult of 'celebrities' into our times through the extensions and influence of the mass media. This trend has been to the disadvantage of most talented and dedicated musicians, and to the decline in the average quality of new musicals offered in the larger theatres.

Tauber performed for the final operetta, Giuditta, which Lehár intended as his Carmen, fiery, with Mediterranean colour, and a sell-out in 1934 for a long stay at the Vienna Opera. Their meetings were only interrupted by the 1939-45 war, Tauber having been persuaded to flee the Nazis on their occupation of Austria, his homeland. He died in England a few months before his friend, and the outcome of their collaboration is still to be heard extensively, recorded again with modern techniques.

Lehár had initiated the 'Silver Age' of Viennese operetta. Musicologist Richard Traubner adds:

Had he striven to imitate Johann rather than Richard Strauss, the operetta picture in the twentieth century might have been radically different. But Lehár was more interested in lyricism and beautiful love songs rather than comedy-through-music and character delineation.

Copyright © 24 October 2019

George Colerick,

London, UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: FRANZ LEHÁR

FURTHER INFORMATION: THE MERRY WIDOW

FURTHER INFORMATION: RICHARD TAUBER