- Thomas Trotter

- Francesco Cilea

- Belarus

- Louis Auguste Florimond Ronger

- Sibelius

- Eric Pettine

- Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho Symphony Orchestra

- Swing low sweet chariot

A Controversial Figure?

GEORGE COLERICK investigates

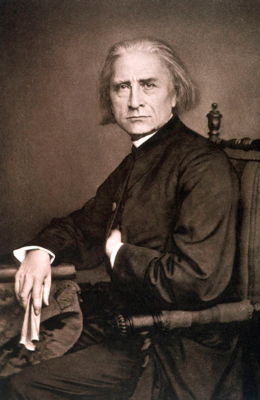

the younger Franz Liszt

The Hungarian cimbalom is a gong-like dulcimer in folk bands, with clarinet and strings. Sacheverell Sitwell (1897-1988), in his biography of Franz Liszt (1811-86), wrote:

The tapping and rattling of the cimbalom is embodied in Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsodies, equally with the chorus of violins and the solos of its leader ... all the effects of a gipsy band, with extraordinary success. In their day, those rhapsodies must have been of immense originality; since then, they have carried the fame of Hungarian music from end to end of the world.

A top view of a modern concert cimbalom, showing the playing area. The strings are struck or plucked.

A few of the first fifteen transcriptions, or at least one, has become overplayed because of its excessive popularity, obscuring most of the others. They were unlike anything ever heard on a solo piano, technically astounding, rising in the style of a czardas, from a relaxed tempo to the wildest exhilaration.

The first page of Homer Bartlett's 1910 edition of Liszt's 'Hungarian Rhapsody No 2' for the University Society Inc.

Scientific research into such areas of folklore did not exist in Liszt's time, so the precise music of the Hungarian peasants would have to wait two more generations for its annotation through musicologists. Liszt relied on music popular in the towns as performed mainly by gipsies, who had often embellished the material. How much was original gipsy music is less important than the fact it gave him a fund of beautiful melodies and exciting rhythms. His skills in transcribing them were such that on hearing the orchestral version of the one numbered two, one might think it unplayable on the piano.

It was from childhood memories of them that Franz Liszt's work on their music originated, and his later art song, The Three Gipsies, is a moving tribute to their culture. He was born in 1811 of Austrian parents. His father worked on the Esterhazy estate which had been linked with a major phase in Haydn's career, on the other side of the Austro-Hungarian border when that was not a political frontier. He never mastered the language, but was proud of being thought Hungarian.

A portrait by Julius Ludwig Sebbers of Franz Liszt's mother, Maria Anna Lager

By adolescence, he was living in Paris thanks to prodigious talent at the piano. His witnessing the first world-famous violinist Paganini was a decisive event as he determined to work hard enough to become a great virtuoso. Paganini's skills were such that once when he played on just one string, the Devil was alongside giving a helping hand. That at least was the witness of a journalist he had probably bribed.

Perhaps one million people believed it. Paganini's compositions were of their kind uniquely difficult to play, and Liszt spent much time transcribing them. In particular, he was the first of many Romantics including Brahms and Rachmaninov to be fascinated by the melodic potential of Paganini's Caprice No 24. He would make the piano rival the violin in speed of note repetition with breath-taking effect. As both men were unusually gaunt, the tag of diabolism was often attached to both by way of explaining their expertise. But Liszt was no charlatan.

His Liebestraum No 3 was once probably the best known love song in Western Europe, thought to be the very idealisation of love. Yet Liszt did not choose to repeat his popular successes. The Consolation No 3 has some melodic similarity, but none of that ecstatic feeling, and is nearer to Chopin's style. Liszt admired him greatly but did not imitate; when Chopin died young, Liszt used some of his valuable time to write a book about him. Great composers were not known to pay this kind of compliment, but Liszt was very generous towards others. Chopin was not inclined to return the compliments about Liszt's creativity.

Being born at a time of the greatest change in music, Liszt was quick to discover what lay beyond, moving away from traditional forms. He led the way in piano music inspired by artistic and literary themes, an approach new for the mid-1830s, leading to Years of Pilgrimage, Year I, Switzerland. This was completed by the age of twenty-five, with impressionistic pieces such as The Bells of Geneva.

Clearly written by the composer of that Liebestraum, the impassioned Petrarch Sonnet No 104 is a piece he revised with much care over the years. On the theme of love's anxieties, he produced several versions for male or female voice, and as a piano solo. It is marked by brief, pregnant phrases, with much note repetition, sighs, highly emotive gestures, forms of instrumental recitative. An early version has the added beauty of the soprano voice, and the later solo piano variant is a fine virtuoso piece. It appeared one decade later in a set, Years of Pilgrmage, Year II, Italy, with two other interpretations of Petrarch sonnets, combining bel canto melody and the operatic style of the 1830-40s with his new techniques. Its companion piece, Petrarch Sonnet No 123, relates to spiritual love and may have inspired Richard Strauss' Italianate aria in Rosenkavalier.

Detail from the earliest known photograph of Franz Liszt, taken in 1843 by Herman Biow

Years of Pilgrmage, Year II, Italy was inspired by the works of the Italian Renaissance, with his Dante Sonata forming the largest item. Dramatic episodes in Dante's Inferno called for unprecedented expressive power on the piano, such as double octaves in a description of Hell. The chord of the diminished fifth dominates the opening, the so-called Devil's Interval, once banned by the Church from all music because of its disturbing sound. There is a poignant interlude in the love story of Paolo and Francesca suffering in Hell.

Paolo and Francesca da Rimini - the 1855 triptych by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, based on 'Inferno' from The Divine Comedy by Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri (c1265-1321), usually known as Dante

Raphael's Sposalizia, the betrothal of Mary and Joseph, depicted a sacred event whose tenderness was translated in what Liszt termed a 'psychic sketch' or 'poetic counterpart'. As an afterthought, he added three short works with melodies by other composers, one from Rossini's Otello, all developed for brilliant virtuosic effect, called Venice and Naples. The gondoliers' song by Ponchielli has a compelling local feeling in the nocturnal dying-away chords, according to Hungarian-born British pianist Louis Kentner (1905-1987). He is specially impressed with the Neapolitan tarantella, the opening swaggering, the theme later transforming to the sound of distant guitars, ending with a paroxysm of gaiety.

Liszt took two classic Spanish tunes, La Folia and the Jota Aragonesa, placing them in brilliant contrast for his Spanish Rhapsody. Pianist John Ogdon (1937-89) wrote that it has one of the finest of all his cadenzas.

In the days before recorded music, the piano and its transcriptions led to unprecedented sales of sheet music, ensuring that families and friends could enjoy operatic drama in their homes, and Liszt's versions are classics. Exceptional demands had been made on his time as soloist, across Europe from Spain to Russia. He was the first great virtuoso to benefit whilst young from the development of railways.

Franz Liszt giving a concert for Emperor Franz Joseph I on a Bösendorfer piano

The age of the public concert hall and larger orchestras encouraged him to create on a larger canvas themes depicting ideas, history and legends. His friend Berlioz's works on literary subjects had pointed the way, but Liszt's innovation was what he termed the symphonic poem. This is a single movement composition not tied down by the strict rules of symphonic structure but growing mainly from one main theme. From 1849, and within a decade, he had created twelve of these, each lasting some fifteen minutes or longer. The form of each work was to be influenced by its subject matter, subjecting his melodies to transformation and integration.

The Preludes' melodic appeal has always made it the most popular of his larger works. That and its rhetoric put it high among several of Liszt's works which many critics find vulgar. Some of the other symphonic poems have interesting cross-references, such as Héroîde funèbre (Heroic Funeral March). Like Berlioz's Triumphant Funeral Symphony, it was intended to pay honour to the victims of the 1830 Paris uprising. Liszt developed it over several years and after he had lived through Europe's revolutionary year 1848, he took a broader political view of the suffering of citizens. So he eventually planned a symphony to commemorate all the dead but it got no further than this one movement.

Other works in the set were from poems, history or classic stories. Sitwell specially admired: Hungaria which he likens to the style of the later Chabrier, with its immediate appeal: Festive Sounds was to celebrate his intended marriage to the Polish Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein, timpani and fanfares, part Meyerbeer, part Rimsky-Korsakov, as Sitwell commented. Finest of all for him, The Battle of the Huns, unique, its opening magnificent and terrifying, the final chorale, bell-like, anticipating Mussorgsky's Great Gate of Kiev.

The oil on canvas painting Die Hunnenschlacht (The Battle of the Huns) from circa 1850 by German painter and illustrator Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874), which inspired Liszt's 1857 symphonic poem of the same name

Sitwell understood why Mazeppa was a theme which attracted Liszt as well as Tchaikovsky, but believed that Liszt gave this violent piece of history a shallow interpretation.

The first Mephisto Waltz, published separately from his symphonic poems, described an episode from the original Faust legend. Its orchestral version brought eroticism into the concert hall, a tale of seduction and gratification during a wild country dance with Mephisto as the demon fiddler. Liszt worked long on this fairly short piece, and on his Faust Symphony (1854). Its three movements are studies of the drama's main characters, the one inhuman. As Mephisto keeps reinventing himself, his personality was ideal for thematic transformation. It is like three linked symphonic poems and Sitwell regarded it as Liszt's masterpiece, describing the Mephisto movement:

Wildness and hysterical excitement run riot; the (earlier) themes are tortured and twisted, given sneering, sarcastic shape: are corrupted and made evil: are presented in triumphant, exultant loudness: they mock and imitate ... (then) are recalled in their original forms, and like the dispersal of the ghosts at cockcrow, the whole atmosphere changes; and the magnificent choral ending brings the Faust Symphony to a close.

The form of the symphonic poem would be taken up by many composers, especially in the following half century.

Liszt's fame among audiences promoted the spreading of the solo piano recital and the media phenomenon of 'Lisztomania'. The adulation he received as a performer was often extreme, though some thought him an exhibitionist all his life. As a young man, he could not resist showing off, and might break several wooden pianos, but only through energetic use. He rebuked Tsar Nicholas I neatly for speaking whilst he was playing. Strange stories, even bedroom farce, related to the behaviour of certain women admirers, such as Lola Montes.

Aged thirty-seven, he moved away from temptation, even standing by his resolution no longer to give paid performances. He would dedicate himself to composition, also performing others' works; he concerned himself least with commercial advantage. He was one of the first performers to attempt to heal with music the sick and mentally disadvantaged. This approach was warmly approved by his friend, Pope Pius IX, though he tired of hearing Liszt's confessions about carnal intercourse, with the words: I've heard enough. Go and tell your sins to the piano.

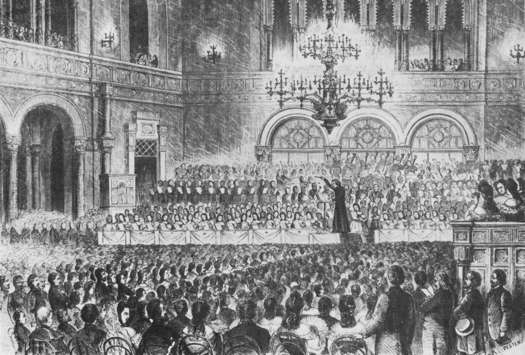

Franz Liszt's 1839 fundraising concert at the Vigadó Concert Hall for the flood victims of Pest in Hungary, where he was the conductor of the orchestra

Liszt had reason to fear his father's prediction that women would be his ruin. He may have been saved through a lengthy, adulterous affair with Carolyne which was stable and supported his creative spirit. This coincided with his being music director (1848-59) at the court of Weimar where his patron provided him with an orchestra and facilities to create a music centre, away from the distractions of the great capitals. His promotion of operas by contemporaries, notably Wagner and Berlioz, was very important.

His proposed marriage to Carolyne fell through in 1861, forbidden by the Church. He sought refuge in religion, his composing gradually turning further in that direction, and to partial residence in Rome.

Remarkably for those times, he lived openly with women regardless of his patrons' and societies' feelings. From an earlier liaison with Marie d'Agoult, he had three children including a daughter, Cosima, who would become the wife of Richard Wagner, though the most important relationship between the two men was musical. Wagner was in the broad sense not a generous man, and unlikely to admit the extent of Liszt's influence.

As a pianist, Liszt was the most famous of the nineteenth century, and by repute an authentic interpreter of Beethoven's sonatas. The severe English critic, Henry Chorley, disapproved of his playing others' new works, yet grudgingly as an early witness, he applauded Liszt's incomparable tonal range:

... the real instrumentalist among many charlatans (in Paris). He can make the strings whisper with an aerial delicacy or utter voices as clear and as tiny as the very finest harp notes. Sometimes the piano becomes a trumpet and a sound is extracted as piercing and as nasal as the tone of a clarion: the power of interweaving the richest, most fantastic accompaniments with a steadily moving melody: fire, poignancy, in flights of octaves and in chromatic succession of chords.

Franz Liszt Fantasizing at the Piano (1840) by Austrian painter Josef Danhauser (1805-45). Pictured in this imaginary gathering, from left to right, are Alfred de Musset or Alexandre Dumas, Hector Berlioz or Victor Hugo, George Sand, Niccolò Paganini, Gioachino Rossini, Franz Liszt (at the piano), Marie d'Agoult and a bust of Beethoven.

Liszt had a reputation for 'flying fingers'; previously pianists bent them over the keys. He exploited certain known techniques to added effect, such as rubato which became a major feature of Romantic expression, and some pianists were tempted to exaggerate. As a composer, he had a liking for the chord of the diminished seventh which in earlier times had been frowned upon as 'sensationalist'. Repeated several times in rapid succession, this can raise tension dramatically. His sonata (not the Dante) was admired by Kentner:

In a short introduction, he introduces three seemingly incongruous elements, then proceeds to demonstrate how these can be welded into a unity of such compactness, such compelling power ... he twists and bends them, rhythmically reshaped to fit into the musical design. Here, the purpose was purely musical, but elsewhere, it could be dramatic.

Kentner refers to Schubert's Wanderer Fantasy, which had intrigued Liszt because of its originality in developing one theme over a whole composition. Liszt adapted the work under the same title, expanding it for piano and orchestra, and covering a wider range of emotional experience.

His songs with piano are generally less admired in Britain than those of Brahms and Schumann, but many of them are very passionate, masculine but eloquent. This may point towards opera which apart from a juvenile effort he avoided. His melodic style was subject to far more influences than his contemporaries'. Yet Liszt's musical personality was very individual; typical of his lyrical side were the main themes of his symphonic poems, Orpheus and The Preludes.

He is one of only a handful of composers whose music has been compiled in recent decades for a ballet. Kenneth Macmillan's Mayerling was about a suicide pact at a hunting lodge in 1882 of two lovers, one the heir to the Austrian throne, four years before Liszt's death.

Throughout his life he had explored new ideas in melody and harmony, and the final verdict on his place and influence in music has yet to be made. For example, in a passionate song he used perhaps the most significant phrase in modern music, the Tristan motif. Yet Richard Wagner would accept the entire credit for this and Liszt was modest enough to acquiesce.

Franz Liszt in June 1867 - photo by Franz Hanfstaengl

Around the age of fifty, Liszt entered a new phase which was to take in the final third of his life. He was turning to matters spiritual, taking minor Holy Orders as an Abbé, which was symbolised by normally wearing a cassock. His composing reflected these changes, increasingly austere and experimental in technique: 'continuing to throw a spear into the future', as Carolyne said.

The younger Liszt remains a controversial figure as a composer, in part unfairly because of the suggestions of showmanship in him. Yet no-one was more broadly dedicated to music, helping where possible the finest compositions of others. Like most, his works were unequal in quality, but the term 'music of the future' was very widely used in his years, and it applied very significantly to his work.

Those who thought Liszt spread his talents too wide were denied by Béla Bartók (1881-1945), who said there was no work in which the greatness of Liszt's creative power can be doubted. He might have been speaking of himself when he said:

What Liszt touched was first crushed to a pulp, then moulded together and so completely reconstructed that his individuality was indelibly stamped on it, as though it had been his original idea.

Copyright © 22 October 2019

George Colerick,

London, UK