SPONSORED: Vocal Glory - Massenet's Manon in HD from New York Metropolitan Opera, enjoyed by Maria Nockin.

SPONSORED: Vocal Glory - Massenet's Manon in HD from New York Metropolitan Opera, enjoyed by Maria Nockin.

All sponsored features >>

Spectacular Productions

GEORGE COLERICK explores the rise and decline

of French composer Charles Gounod

How you come down after that I do not know. Maybe you come down a notch or two ...

A UK Classic FM radio announcer suggested this one early morning in March 2006, referring to the impact of a melody seemingly from another age, ennobling, with a grandiose beauty. Perhaps he found it most inspiring. Or was he simply astounded? It was composed in 1885 and if radio had existed then, the comment would have been in a more devotional spirit. It was widely thought to be one of the most inspired melodies to come out of that century. Not many would have disagreed.

Its audiences at the time had come to expect such grandeur from the oratorios of French composer Charles Gounod (1818-1893). It had deep religious significance for millions of French and English speaking Christians. It was the Judex from Mors et Vita, concerned with divine judgement in a sequence of religious works including the other giant oratorio Redemption (1882), both premiered at Birmingham festivals.

By 1885, Gounod's last opera The Tribute of Zamora had known moderate success with some fifty performances but was to disappear from the stage whereas his Faust of 1859 was then probably the most performed of all operas. One cannot measure now whether stage or concert was the greater general appeal for his music, but he enjoyed a fame others could only hope for. It was one which would decline steadily into the following centuries.

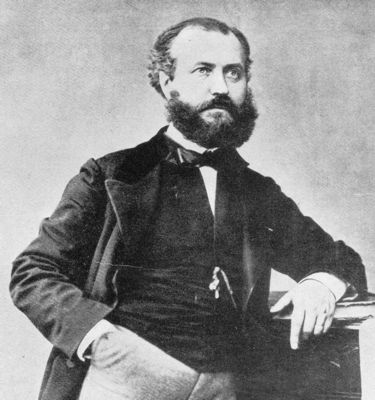

Charles Gounod in 1859

As a youth, Charles Gounod heard the great soprano, Malibran, singing Rossini, and later had an affair with her sister, Pauline Viardot, who was the last of a distinguished musical family. She had premiered The Prophet in 1849 and had helped to place in a commercial Parisian theatre Gounod's first opera, Sapho (1851). It was to be as a virtuoso piece for Viardot, who however was reaching the end of her career.

In the spirit of a classic Greek pastorale, it relates to the desertion of the poetess from Lesbos by her male lover. It showed in the finale the young Gounod's gift for a beautifully restrained lyricism. For dramatic interest, it uses the well-tried device of a song contest; here the male rival sings a martial verse, losing out to Sapho.

There is triangular love intrigue which would become familiar in Gounod's operas of which he wrote eleven more. Three were comedies on a modest scale, but most of the others were spectacular productions. La nonne sanglante (Bleeding Nun, not translated) was a melodrama which several composers had rejected, by Scribe in the manner of Robert the Devil. Meyerbeer was impressed, not knowing if he had a follower or a rival. Yet already established successfully in Church music, Gounod was not in sympathy with sinister underworld imagery, and this failed to inspire his best imagery. Berlioz had started on the same play by Scribe, until it was clear he could not get it performed in Paris; it would have suited his style better.

Gounod needed more lyrical subjects which explains why he later abandoned sketches for Ivan the Terrible. One sequence ended up in the fine Act I finale of a later opera, The Queen of Sheba (1862), for her legendary arrival at King Solomon's court. The French Emperor objected to aspects of this play, specially the Queen rejecting Solomon for a commoner. In a London production, the plot and its characters were soon being changed. Gounod was depressed by the apparent failure of this most ambitious work, and it probably does not deserve the neglect which continues until now. It would make interesting comparison with Karl Goldmark's 1875 opera of the same title.

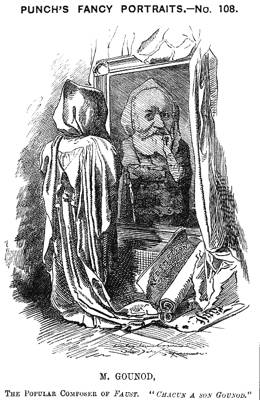

A caricature of Gounod by English cartoonist and illustrator Edward Linley Sambourne (1844-1910) from Punch, 1882

Before that, in 1859, Gounod had his greatest operatic success, Faust. The story of a male seducer, his victim and the surrogate Devil would intrigue us much less today, but through much of the nineteenth century, it seized the Romantic imagination like no other. By the 1850s, it was well known in the Parisian music theatres, not least in several burlesques. It led to an earlier work by Hector Berlioz (1847) which akes for interesting contrast, with its more detached, classical approach.

Gounod had found an expressive power which went well bayond opera purely as a collection of beautiful melodies. It enabled him to achieve a breakthrough, then overdue in Paris, towards a more naturalistic operatic style. This was perhaps helped because unusually, the plot had no heroes, just two characters briefly enjoying then suffering through a common human experience. In the intimacy of the lovers' feelings, Gounod achieved a fusion of words and music to a degree most of his French predecessors had not reached.

Coloratura singing may be very exciting, but can hold up the drama, and Gounod reduced it in Faust, except in the much admired jewel song. He also showed skills in dramatising the crowd scenes, such as at the ball where Professor Faust and a young girl Margarite first see each other; and a soldiers' homecoming including her brother.

The Professor, ageing and bored with the intellectual life, is susceptible to the offer of returning to his youth, acquiring a girl of his choice, and enjoying magically bestowed powers. The price to be paid is surrendering his soul to the Devil.

Legends are often concerned with life's deepest values and decisions, and Faust symbolises those who have made fatal choices. The Devil's emissary is Mephisto, who restores Faust's youth and provides the casket of jewels with which Faust will seduce Margerite. He soon tires of her to embark on wondrous adventures with his benefactor.

A still from the film Faust aux enfers by George Méliès (1903) - the final scene unfolding in Hell, when Mephisto emerges from the basement and spreads wide bat wings, in the middle of the general jubilation

Mephisto is one of the most attractive villains in all opera, engaging many composers' interest. Gounod gives him perhaps the best of all laughing serenades, alongside Mozart's in Don Giovanni. Audiences were delighted with music which had Mephisto presenting specious arguments, telling funny stories, impersonating a holy man, flirting with a widow and performing miracles on wine. This talent for musical humour is a rare facility which Gounod used in his three modest but successful comic operas.

Margerite is left pregnant, and has a child; but Mephisto is not finished with her. The Devil now wants her soul and she is driven to temporary insanity. She recovers to seek God's help, and has a final confrontation with the two men before Mephisto casts Faust down to hell. This powerful trio is the climax and her salvation is accompanied with music in the elevated style of Gounod's oratorios.

His original version of Faust was seen in a commercial theatre, but unlike Verdi, Gounod had some defects in his judgment of dramatic suitability. He was under the influence of impresario Carvalho and his prima donna of a wife, who might have deflected his dramatic intentions in several operas. Fortunately, he was persuaded to move a soldiers' chorus from his unperformed Ivan the Terrible to Faust where it had an immense impact. It became so popular along with the waltz that they soon were being played by bands right across Europe.

To render Faust suitable for the state-subsidised National Opera, it had to be converted into grand opera. That included a substantial ballet sequence, which drew on extra literary material, Faust being transported by Mephisto to ancient Greece and a meeting with Helen of Troy. Its melodious ballet music became in turn a popular classic; yet in modern productions it is mainly truncated or eliminated as unnecessary for the main plot. This is an obvious way for saving costs. The original medieval scenario is now often replaced by one in the nineteenth century. A recent Welsh National Opera version has citizens in crinolins and stove-pipe hats, which enhances the effect of bourgeois condemnation of sexual 'immorality' in the 1860s. That is of the greatest relevance because Gounod had to please his audience, notably by retrieving Marguerite from the status of a 'fallen woman', deceived by the Devil's magic.

Margarite's garden in Act III of Gounod's Faust as presented in the original 1859 production at the Théâtre Lyrique in Paris by set designers Pierre-Auguste Lamy (1827-1883), Charles-Antoine Cambon (1802-1875) and Joseph Thierry (1812-1866)

Faust shows tender feelings for her which are absent in the original play where Mephisto had felt free to mock his carnal interest. Precisely until fighting the war of 1859 in Italy, France's popular conception of war had been for decades one of Napoleonic glamour, whereas the real horror of every battlefield was then to be brought home, infamously at Magenta in Italy. Contemporary versions may have many of the soldiers returning from the war on crutches or stretchers, but to the triumphant music.

Margarite evolves from naive girlhood to disillusioned mother, and Faust is transformed by magic from elderly, reflective professor to irresponsible young man. These changes have to be reflected in the singing styles, along with Mephisto's devilish physical transformations and magical acts. As a result, in Europe's great opera houses, Faust needed the finest and most versatile of Europe's singers, and this contributed to its unprecedented fame over decades.

Yet since sex is today considered an enjoyable option and the Devil has died, modern conceptions of the opera's theme, as distinct from Goethe's philosophical play, have been devalued, and with it the opera's reputation. Carmen is now preferred and admired as a realistic tragedy, though Bizet was once a youthful Faust enthusiast. Nor is Gounod's historic position in French opera so widely appreciated, though his stylistic development paralleled that Verdi had applied to Italian opera one decade previously. It would seem the process went no further, as Gounod could not repeat the success of Faust. It will survive on at least its wealth of fine melodies.

Mireille (1864) has a story similar as far as a love affair which society disapproves to fatal results. The opera has the pure lyricism evident in Sapho, and is now valued as highly as Faust, being performed in its original form since 1939. The overture and girls' opening chorus express the happiness of carefree youth, and the early scenes, Mireille's lust for life. Local songs of the Midi added to the work's sunny appeal and were enthusiastically received. Yet the girl's life is to be destroyed because she intends to marry a young man without property. The music's warmth must have suggested to Carvalho that the tragic end should be avoided, which reduced the poignancy of the drama. The original plan with Mireille's death from sunstroke is now restored in the dramatic church scene.

The Act II finale of Gounod's 'Mireille' in the original 1864 production

If Mireille had strong appeal in evoking the South of France, Romeo & Juliet (1867) had an obvious appeal, and it did not disappoint. The composer responded ideally to the love theme and the libretto by Michel Carré and Jules Barbier. It respected the original text as far as possible, bringing the important ballroom scene which set off the violence even nearer to the beginning.

While innocent of future unhappiness, Juliet sings a waltz song which was to become almost as familiar away from theatres as Margarite's jewel song. There are an exceptional number of fine duets for the lovers, four. Years later for the grand opera version, there was the compulsory ballet for Act III, very well received but no longer used, though unfortunately the recitative has tended to stick.

It was eight years before Gounod attempted another grand opera. Three more were to come, but are now rarely performed and not known to English speakers. Gounod was attracted by the theme of Christian martyrdom when he chose Polyeucte, but its seventeenth century classical text by Corneille was the opposite of what can be associated with Romanticism. After that, he lost the services of his long-serving librettists, Carré and Barbier.

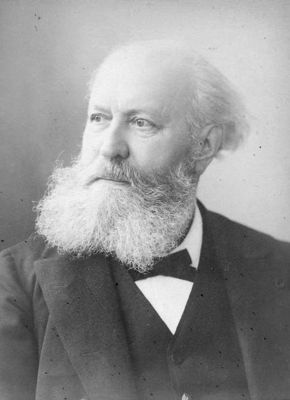

Charles Gounod in his later years

Marie-Anne de Bovet wrote a sensitive book on Gounod shortly before his death, and dismissed the first of these operas about a king's favourite, Cinq-Mars (1877), as hastily written and not worthy of further remarks. She commented on The Tribute of Zamora :

Sombre without being dramatic, monotonous and incoherent, with no really interesting character ... Gounod has lost himself in a confusion of styles.

Charles Gounod - His Life and Works by Marie-Anne de Bovet and Charles Gounod, republished 2013 by TheClassics.us

She did praise a war chant, the ballet and a mad scene. A melodrama, its vigour seemed to suggest renewed inspiration. But the year was 1881, thirty years after Gounod's first essay, and critical opinion would soon conclude there was much repetition in these works of ideas from earlier successes. Gounod tried no further in opera.

The 1870 war and siege of Paris had proved a watershed in the theatre and new styles were emerging. Massenet by the 1880s was sustaining a consistently high level in his operas with exceptional variations of theme and even style. He had admired and learnt from Gounod and his melodies sometimes have a striking affinity but uses more artifice and to great effect. Whereas he was more of a detached observer who could rise to sudden heights of passionate declamation, Gounod was sentimental and needed more space to sustain his lyricism. This helps to explain why Faust, Mireille and Romeo & Juliet are considered the most durable of Gounod.

Copyright © 17 October 2019

George Colerick,

London, UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: CHARLES GOUNOD