VIDEO PODCAST: Find out about composers from unusual places, including Gerard Schurmann, Giya Kancheli, Nazib Zhiganov and Nodar Gabunia, about singing in cars, and meet Jim Hutton from the RLPO and some of our regular contributors.

VIDEO PODCAST: Find out about composers from unusual places, including Gerard Schurmann, Giya Kancheli, Nazib Zhiganov and Nodar Gabunia, about singing in cars, and meet Jim Hutton from the RLPO and some of our regular contributors.

An Innate Songster

On George Gershwin's birthday,

GEORGE COLERICK takes a critical look

at the composer of 'Rhapsody in Blue'

From conversations around 1950, Leonard Bernstein quotes a music production manager stating that George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue throughout its variety and changes of mood and tempo breathes America - the people, the urban society, the pace, the nostalgia, the nervousness, the majesty. Bernstein wanted to qualify the praise because of defects in symphonic development, alleging Tchaikovsky-like sequences, Debussy meanderings and pianistic fireworks in the manner of Liszt. He suggests that certain sections could be removed without damaging the rest; there was no inevitability about it all. He called the equally enjoyable Piano Concerto the work of an apprentice learning fast.

In due course, Gershwin acquired the skills to orchestrate another concert work, An American in Paris, inspired tunes and rhythm, perfectly harmonised. Bernstein noted that it showed skills learnt from such as Richard Strauss and Ravel in linking and combining themes. An original symphonic thinker had not yet emerged.

It was a cultural reality that by the time of this conversation an abundance of great new melodies no longer flooded the stage as they had done in the times of Rossini and Verdi. That generalisation is related to the rise and fall of civilisations. Though a claim could be made for Kern and a few others, Gershwin was the rarest of exceptions. He was prolific in fine melodies which is why the production manager, unnamed, had cited him, worried that Bernstein's latest show had no 'hits'.

Leonard Bernstein in the 1950s

Years later, Bernstein would remedy this defect with such songs as Maria. One explanation was that he and Gershwin had come from opposite sides of the musical tracks. Bernstein had started off writing symphonies. This had involved becoming not just a song writer giving audiences what it was assumed they want, but an original one. Gershwin's way had been the more natural, an innate songster, to become as Bernstein believed the finest melodist since Tchaikovsky. He had grown into a serious composer, and with a rare sense of what works best in the theatre. That was where his destiny lay, and with one inspired opera before his progress was cut short by death.

Bernstein admired the entire opera Porgy & Bess as it had been written, but since Gershwin's death, productions had been turned into an 'operetta', such as by replacing the sung-speech with words. The manager suggested that was proof of a defect in the original version.

For 12 February 1924, in a pretentiously named 'experiment in modern music' at the Aeolian Hall, band leader Paul Whiteman would entertain New York's musical celebrities with twenty-four items under eleven headings. They might have been better advised to stay at home, except for the penultimate work which starting with its astonishing seventeen-note clarinet glissando was to be the outstanding work of the night. Gershwin always excelled in playing his own works at the piano, the leading instrument in his Rhapsody in Blue which had been orchestrated by composer Ferde Grofé for Whiteman's large jazz band. Years later, a Second Rhapsody had a lesser impact, though Gershwin had good reason to believe it broke new ground starting as background for a film, then expanded. It revealed greater depth of feeling, and even by his standards, its forceful rhythms are intriguing.

Gershwin's future reputation for symphonic composition would rest on two works before he proved himself in an even greater challenge - opera writing. He orchestrated his successful Concerto in F - in a new American style, it has some affinities with Aaron Copland's.

If Gershwin had given it the title of fantasia or burlesque, he would have avoided much criticism about its form. The occasional glances towards Liszt and others could then have been seen as affectionate reminiscences. Modestly he described it as a sequence of musical paragraphs. The opening movement has a shock of contrasting themes, whilst a Charleston waits in the wings and eventually dominates. The slow movement is a leisurely, sophisticated comment on the blues, and the finale, suitably replacing the traditional rondo, is a sequence of themes delivered at an extremely fast pace. Whatever titles he chose, it was predictable that the combination of piano and orchestra would be a valuable option for the future. So he wrote a set of variations on I've got Rhythm.

An American in Paris followed two years later in 1928 and is most widely known from the film of the same title (1950), one of Hollywood's greatest musicals. There it is the accompaniment to an inspired ballet with a scenario on the Moulin Rouge and its famed artistes of the 1890s. For the concert hall it was a welcome innovation, a colourful symphonic poem describing a young man's exuberant romp around Paris with the confidence to capture the girl of his choice. It could have been heard as symbolising America's seduction of the Old World with the latest style of syncopated music. As a story told in episodes, it has a verve which can be likened to Till Eulenspiegel. Gershwin included four of his exuberant melodies; the fifth was a blues, nostalgic for the USA; the sixth, which had arrived decades previously from Spain via Paris, remains probably Western Europe's most compelling street song, the Matchiche.

As a youth, Gershwin had started composing for Tin Pan Alley, but its basic requirements were assembly-line production and he soon out-grew them. The popular formula was economical in music resources: one eight-bar phrase, repeated, then a different eight-bar phrase for contrast, then the first one again, but slightly modified to give a conclusion (cadence). This created a thirty-two-bar tune, which could be repeated with different words, the object being to fit neatly onto the normal ten-inch gramophone (phonograph) record. Lady be good was a clear example. This song was also the title of his first unqualified success as a musical (1923) and introducing the Astaire siblings. Later the show was enhanced with the charismatic singer, Ethel Merman, whilst some of the most famous big band instrumentalists of the future accompanied. Unlike most composers, Gershwin might have to select from as many as twenty good songs for one show.

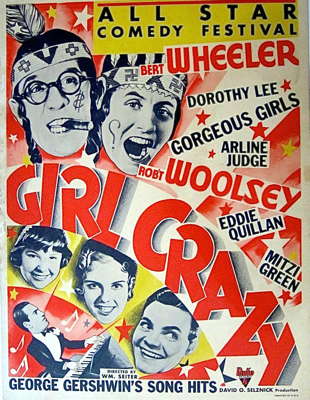

Window poster for the 1932 film Girl Crazy

Ira Gershwin's lyrics apart, the stage plays used for 1920s Broadway musicals tended to the banal, and the Gershwins deserved better. It was in 1992 that a composite musical arrived to critical acclaim. It was Crazy for you partly based on Girl Crazy (1930), with some dozen other 'hits', escapist entertainment at its wittiest, versatile performers, a song-and-dance spectacular. It was more than a worthy tribute to Gershwin; it pointed to his classic status over half a century after his death in 1937, aged thirty-eight.

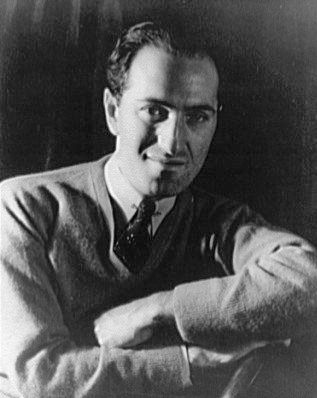

George Gershwin in 1937

He often worked alongside Jerome Kern, an older, classically trained, composer of more sophisticated songs. His finest included All the things you are, in its original 'operatic' shape consisting of an arresting introductory phase, then one full melody (refrain), leading to the climactic second one (chorus). The emotional effects there are enriched by fluctuations of major and minor scales, and other subtleties.

Both men had gained musically from their Jewish backgrounds, immigrants from Russia. Gershwin said he learnt from Kern how songs from musicals could be superior to 'popular' ones. This induced him to upgrade one of his best ideas which he had first withdrawn from the stage, probably because audiences had found it too intense, out of place. So he rewrote the song. The Man I love, giving it the introductory refrain it deserved.

Opera director Reuben Mamoulian described George's skills at improvisation:

He would draw a lovely melody out of the keyboard like a golden thread, then he would play with it, and juggle it, twist it and toss it around mischievously, weave into unexpected intricate patterns, tie it in knots and hurl it into a cascade of ever-changing rhythms and counterpoints.

The gift of being able to compose to a given text also set him apart from most, and a valued partnership developed from 1924 when his older brother Ira became his lyricist. To broaden his perspective, he visited Paris and Vienna, meeting many important composers. In 1928, Emmerich Kálmán's Duchess of Chicago gave the Charleston rhythms a leading part for the first time in operetta, and Kurt Weill's subversive Threepenny Opera appeared. That year in Vienna, Gershwin met both men and with his feel for stagecraft may have gleaned new ideas.

Popular stage hits slow down dramatic movement, reducing the drama's importance in musicals. One option was to seeking greater cohesion of words, music and action, using a manner more declamatory than traditional ballad. Gershwin would have known Weill's music, though there is no evidence he used it as a model. Some of his later works showed such interesting features, starting with Strike up the Band. They contained fewer lyrical songs and 'hits', which may explain why they have not been so much performed in recent decades. He was moving into 'serious' musicals, more satirical.

Gershwin was studying composition to face the ultimate dramatic challenge. At that time, operettas defined musicals requiring voices of operatic strength, but he would pass over this agreeably escapist option to compose a full-bloodied opera. That had to be the powerful but depressing theme of his choice which came from a novel then adapted as a successful play. Porgy and Bess expressed sympathy for the down-trodden and its protagonist, a disturbed, crippled black beggar.

Many of his associates disapproved of this venture by Gershwin. Should not the first opera about blacks be more elevated? There was no shortage of black composers, especially in the world of jazz. Surely 'popular' arias such as Summertime were more suited to musicals? Yet Romantic operas had always produced catchy, singable hits, and despite being 'modern', this one was also to be in the Romantic fold, notably in his inspired harmonies and rhythmic variety.

Gershwin wrote at least one impressive rag, Rialto Ripples, in the manner of Scott Joplin. He knew of that man's exceptional talents even for musicals. He may have known that only one European had composed an opera displaying the victimisation such people suffered: Delius' Koanga, and that as long back as 1897. Gershwin's long-standing interest in jazz encouraged him to go further, after visiting local communities and listening to speech inflections in the search for musical authenticity. His progress in composition was so rapid that by 1934, Porgy and Bess was ready, performed by an all-black cast and destined to be a long-playing success. It enabled him to prove himself in new areas such as characterisation and ensemble writing. This impressive score seemed to point to ways forward for his restless creativity; but fate decided otherwise.

Many have compared Gershwin's melodic gifts with those of Schubert who died at the age of thirty-one. His last songs were among his greatest; Love walked in perfectly expresses swooning rapture, and his final comment (to his brother) described it as Brahmsian.

London UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: GEORGE GERSHWIN