DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Music and the Visual World, including contributions from Celia Craig, Halida Dinova and Yekaterina Lebedeva.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Music and the Visual World, including contributions from Celia Craig, Halida Dinova and Yekaterina Lebedeva.

VIDEO PODCAST: Discussion about Bernard Haitink (1929-2021), Salzburg, Roger Doyle's Finnegans Wake Project, the English Symphony Orchestra, the Chopin Competition Warsaw, Los Angeles Opera and other subjects.

VIDEO PODCAST: Discussion about Bernard Haitink (1929-2021), Salzburg, Roger Doyle's Finnegans Wake Project, the English Symphony Orchestra, the Chopin Competition Warsaw, Los Angeles Opera and other subjects.

RESOUNDING ECHOES: Beginning in 2022, Robert McCarney's occasional series features little-known twentieth century classical composers.

RESOUNDING ECHOES: Beginning in 2022, Robert McCarney's occasional series features little-known twentieth century classical composers.

Inherent Challenges

JEFFREY NEIL has some issues with San Francisco Opera's production of Wagner's 'Tristan und Isolde'

Richard Wagner's adaptation of the medieval Tristan und Isolde tale was considered unperformable after he completed it, not just because of the exceptional vocal endurance that it requires, but because very little happens. Wagner stripped Gottfried von Strassburg's colorful adventures and distilled it into a Gnostic elixir of love through death, inner light through darkness. As Paul Curran admits in his Director's Note to the San Francisco Opera's production, the opera requires 'ways to keep the audience engaged ... using lighting, set design, and thoughtful movement to create visual interest while staying true to the work's meditative quality'.

Annika Schlicht as Brangäne and Simon O'Neill as Tristan in San Francisco Opera's production of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Curran's production responds to these stringent demands with a brutalist monochromatic set, static blocking, and perplexing choices of costumes; and conductor Eun Sun Kim tamped down the volume and the energy behind the orchestration.

South Korean conductor Eun Sun Kim (born 1980), San Francisco Opera's music director until 2031 (left, photo © 2023 Cody Pickens) and Scottish opera director Paul Curran (born 1964, photo uncredited)

Staging Tristan is, admittedly, not for the faint of heart. Part of this is, ironically, because the music is so engulfing, the Tristan chord with which the opera begins, so mesmerizing and obsessive in its various iterations, that it insulates the listener from dramatic action. But there is also something inherently unpalatable about Arthur Schopenhauer's philosophy, which inspired Wagner: in the 'daytime world', suffering is the norm, because the will of the individual must 'strive against itself' endlessly, tortured and pushed along by insatiable desire and yearning. In death there is a solution because, for example, lovers like Tristan and Isolde, no longer have to battle all the things that separate them in the 'phenomenal world'. When they die, they are 'awakening from the dream of life', according to Schopenhauer.

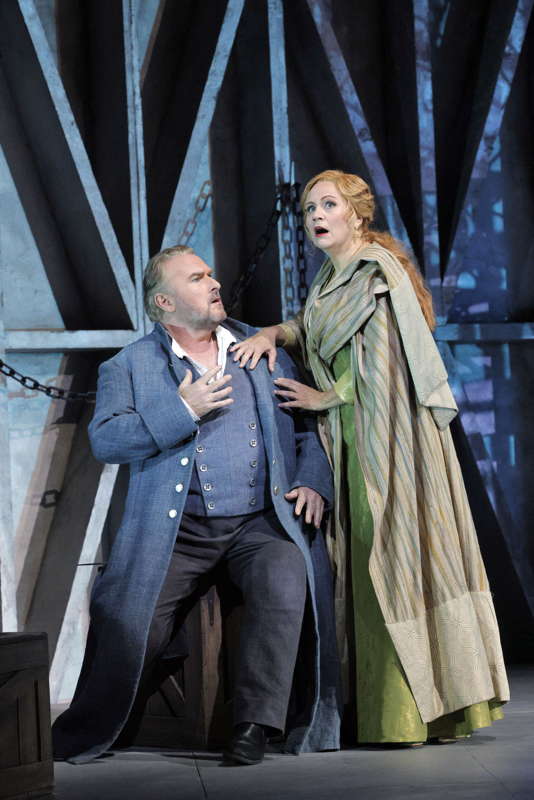

Anja Kampe as Isolde and Simon O'Neill as Tristan in San Francisco Opera's production of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Over five years after Wagner completed Tristan und Isolde King Ludwig II finally brought the opera to life on the stage by pouring his vast resources into producing it in Munich. The Swan King, whose genius was responsible for the fantasy rooms, grottos, and a rooftop garden in various palaces around Bavaria, was also notorious for putting on private opera performances with extravagant sets and costumes. He was such a die-hard aesthete he once had a diva, whom he considered ugly, hide behind a tree while she sang for him. Infatuated with the man and the music, King Ludwig helped Wagner stage his paean to erotic love.

Anja Kampe as Isolde and Simon O'Neill as Tristan

in San Francisco Opera's production of Wagner's

Tristan und Isolde. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

King Ludwig would have been taken aback by Curran's set. Act I reveals the structural scaffolding of the ship's hull, an x-ray into 'bones' of the ship. Everything is colorless, and the lighting is washed out. This does not so much 'update' the experience, as strip the Gesamtkunstwerk - 'Total Work of Art', which Wagner championed - of its immersive quality. If it were possible, the second act further punished the senses with what appeared to be a kitsch interpretation of the Nordic tree of life spray painted silver to blend in monochromatically with the backdrop.

Anja Kampe as Isolde and Simon O'Neill as Tristan

in San Francisco Opera's production of Wagner's

Tristan und Isolde. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

In the third act, the setting for the most sublime music, the coup de grâce was the resurrected ship set from Act I, deconstructed and thrown helter skelter on the stage.

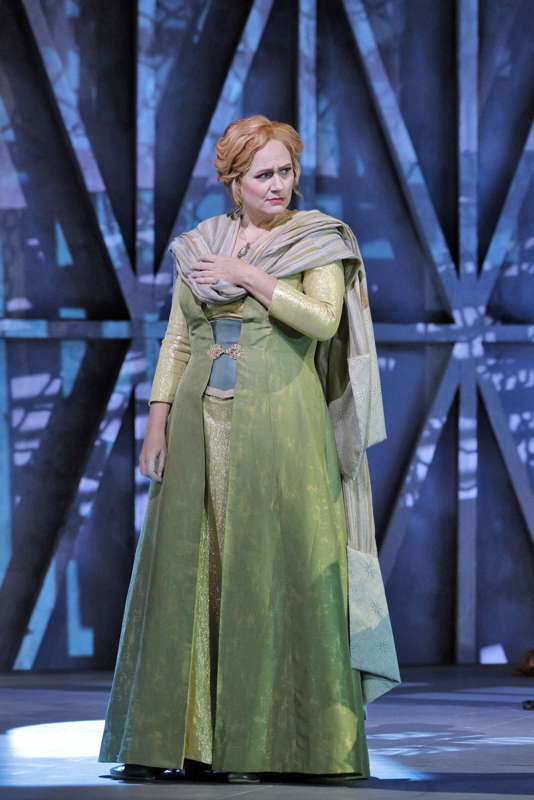

Anja Kampe as Isolde and Simon O'Neill as Tristan in San Francisco Opera's production of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Every Isolde will be judged by her 'Liebestod', and Anja Kampe's interpretation was competent. Wagner actually called that piece the 'Transfiguration', not the Liebestod (which is in the Prelude) and not even an 'aria', since it was supposed to be something so otherworldly it defied operatic convention. This is the piece that Kirsten Flagstad (easily the most famous Isolde) observed had obsessed audiences: '... people in the audience would shout one word: "Liebestod!" That cry, I am sure, will haunt my sleep to the end of my life'. Unsurprisingly, Wagnerites hold high expectations - the echoes of Flagstad and Jessye Norman haunt our sleep. Kampe hit the notes somewhere smack in the middle of them, but there was something tired and grasping, rather than transcendent in her interpretation. She was much better in the feisty 'Long Narrative' in Act I before drinking the love philtre.

Anja Kampe as Isolde

Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

German mezzo-soprano Annika Schlicht, as Brangäne, had the gravitas and vocal prowess to sustain one of the most dramatically interesting parts of the opera in her dynamic with Tristan and Isolde on that painful journey to Cornwall. Given how stony-faced almost all of the players were throughout the opera, Schlicht also stood out for her acting.

Annika Schlicht as Brangäne

Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

The thirty choristers in Act I antagonize Isolde, first by rubbing salt in her wounds for being carried off as a trophy and then, after she drinks the love potion, stressing her about being separated from Tristan. They are essential in conveying that raucous Teutonic spirit that Wagner was bringing to opera. Beautiful as the sound was, I wanted more of it - louder and more enveloping. The same goes for the orchestra, which although it did not skimp on the instrumentalists demanded by the score, nevertheless felt muted and as if the tempo had been dialed down just enough to make it all sound lugubrious.

To Wagner's dismay, his wife Minna pronounced Tristan and Isolde to be an 'odious and slippery couple' - no doubt also because of Wagner's mistreatment of her while having an affair with the patroness of the opera, Mathilde Wesendonk. But it also alludes to the innate danger of the parts. As Tristan, Simon O'Neill kneels down and hugs Isolde's knees or is collapsed pathetically on the floor. In pushing this oedipal take on the relationship, a dynamic emerges that is unsettling, that feels prurient rather than erotic. Act III subverts the potential for romance and transcendence by heaping a mess of blood-soaked towels on the floor while Tristan bastes in his own blood in an armchair.

Wolfgang Koch as Kurwenal (left)

and Simon O'Neill as Tristan.

Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

One could overlook the static blocking with actors and singers frozen in place for long stretches of time, singing with expressionless faces. I might also have been perplexed, but dismissed the strange mish mash of twentieth-century garb and pseudo-medieval costumes had the music soared. But, more seriously, the principals' voices did not complement each other; they did not go from strength to strength together as the vocal marathon requires. In his role as Melot, tenor Thomas Kinch had a strong, youthful clarion voice and in contrast looked the part of Tristan. With the brightness and timbre to carry the part, I would have loved to have seen him as a lead. Audiences, however, will get a chance to see the Adler Fellow take on the role of Don José for one night only, tonight, on 26 November 2024.

Welsh tenor Thomas Kinch

Tristan und Isolde was never going to be easy - because of the length, how few people have the strength and stamina to sing the principal parts, and because of the inherent challenges in staging it. Eun Sun Kim's commitment to presenting one Wagner opera per season for the duration of her contract (until 2031) will present many more opportunities for her and a talented director to bring to life all aspects of Wagnerian Total Works of Art.

Copyright © 26 November 2024

Jeffrey Neil,

California, USA