WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata No 26

- René Jacobs

- Samuel Carl Adams

- Turnage

- Institute for Young Dramatic Voices

- Iuventus Ensemble

- Janis Martin

- Jenni Brandon

ARTICLES BEING VIEWED NOW:

- Régine Crespin

- Hector Berlioz

- Ruth Railton

- Marián Varga

- Profile. A Very Positive Conductor - Paul Bodine talks to Los Angeles Opera's Music Director Designate, Domingo Hindoyan

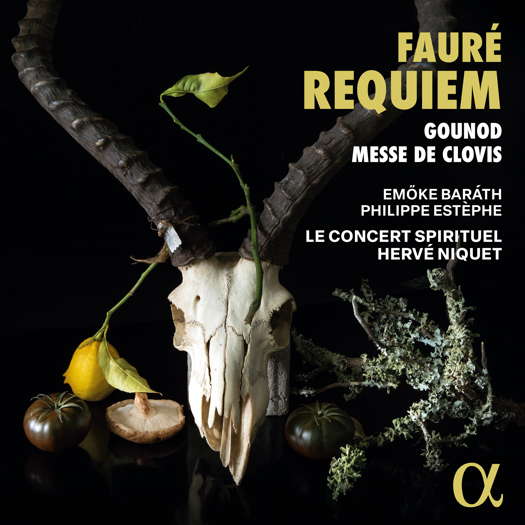

A Superb Compendium

GERALD FENECH listens to Emőke Baráth, Philipe Estèphe and Le Concert Spirituel conducted by Hervé Niquet

'... the best of French late romantic sacred music in vibrant and heartwarming performances.'

After the Revolutionary period, the restoration of religious worship in 1803 brought a renewal of sacred music in France. The first Romantic period of French church music, still adhering to the Classical style, was succeeded by works of highly theatrical character. Unsurprisingly, the standard choral Mass was largely replaced by settings of the Requiem, whose inherent pathos demanded grand harmonic and instrumental effects: its most prominent composers included Berlioz, Thomas and Saint-Saëns.

After 1870, the spectacular gave way to a more ethereal mood of recollection. Intimacy was expressed through a return to a simple purity, ideally embodied in the models of Gregorian chant and the Renaissance motet. It is in this neo-Palestrinian context that Gounod's Messe de Clovis and Fauré's Requiem appeared only a few years apart.

On 7 May 1891 Charles Gounod (1818-1893) began composition of the Messe de Clovis, whose posthumous 1896 edition bears the title page inscription: 'Composed for the 14th Centenary of the Baptism of Clovis of Reims, 25th December 496'. Though the complete version of the score includes a Prelude with grand organ and fanfares for trumpets and trombones, the edition published by Choudens is for the more modest forces of a choir and choir organ. The writing for the voices revives the style Gounod had experimented with in his Viennese Messe vocale: pure Palestrina and neo-Renaissance from start to finish. Gounod is here taking inspiration from a system rather than slavishly copying it. The Kyrie does not adopt the usual supplicatory tone: instead the choir in a resolute forte attack proclaims its confidence in the spirit of the victorious monarch.

Listen — Gounod: Kyrie (Messe de Clovis)

(ALPHA 1014 track 8, 0:10-1:03) ℗ 2024 Alpha Classics /

Outhere Music France / Palazzetto Bru Zane / Le Concert Spirituel :

The Gloria begins by invoking the spirit of traditional French Christmas carols before the entry of the massed choir bringing harmonic complexities and exploiting the lower registers.

Listen — Gounod: Gloria (Messe de Clovis)

(ALPHA 1014 track 9, 0:33-1:26) ℗ 2024 Alpha Classics /

Outhere Music France / Palazzetto Bru Zane / Le Concert Spirituel :

For the rest of the Mass Gounod continues his exploration of a brilliantly handled 'historicizing' style. The final Agnus Dei in particular exhibits a contrapuntal quality entirely free of any rigidity or pedantry.

Listen — Gounod: Agnus Dei (Messe de Clovis)

(ALPHA 1014 track 13, 2:19-3:16) ℗ 2024 Alpha Classics /

Outhere Music France / Palazzetto Bru Zane / Le Concert Spirituel :

Among the many requiems composed in France during the nineteenth century, the one by Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) stands out through its lasting posterity - it has become a musical symbol for French funeral monument - as well as through its structure and the originality of its inspiration. The work departs from the sequence of the pieces from the Ordinary and Proper of the Requiem Mass that composers usually set to music: here is no Gradual, no Prose, there is no Dies Irae and no Benedictus. Here Fauré also avoids the dramatic vein generally cultivated by his predecessors, giving the work instead a rather 'angelic' atmosphere.

Listen — Fauré: In paradisum (Requiem)

(ALPHA 1014 track 7, 0:01-0:48) ℗ 2024 Alpha Classics /

Outhere Music France / Palazzetto Bru Zane / Le Concert Spirituel :

These distinctive traits can scarcely have been dictated by the circumstances of the work's first performance on 16 January 1888 at La Madeleine and conducted by Fauré himself. Yet it seems significant that its composition immediately followed the death of both Fauré's parents. Its incomplete 1888 version was followed in 1893 by a performance including all the movements we know today, but in an orchestration excluding violins and woodwind - as presented in this recording.

Later, at the request of his publisher Hamelle, who found this instrumentation too unsettling, on 12 July 1900 Fauré had a new version for full orchestra performed, an arrangement in which his pupil Jean Roger-Ducasse probably had a hand.

This superb recording additionally presents two further pieces of French late Romantic sacred repertoire. First, 'O Salutaris' by Louis Aubert (1877-1968) for soprano, violin, harp, organ and choir, recalling the luxurious grandeur of the great galleried churches of Paris, with celestial harp arpeggios and an ecstatic chanting in the violin over the mellow piping of the organ: here the soloist and choir are adoring Jesus at the Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament.

Listen — Louis Aubert: O Salutaris

(ALPHA 1014 track 14, 1:15-2:13) ℗ 2024 Alpha Classics /

Outhere Music France / Palazzetto Bru Zane / Le Concert Spirituel :

The Adagio for violin and organ by André Caplet (1878-1925), apparently composed in 1890, was rearranged under the title 'Invocation' as the third movement of his Feuillets d'album for flute and piano published in 1901. It is one example among many of the late nineteenth century instrumental meditations for violin or cello and organ intended for use in services that were rather more elaborate than usual.

Listen — André Caplet: Adagio pour violon et orgue

(ALPHA 1014 track 15, 2:20-3:14) ℗ 2024 Alpha Classics /

Outhere Music France / Palazzetto Bru Zane / Le Concert Spirituel :

This is a superb compendium of works highlighting the best of French late romantic sacred music in vibrant and heartwarming performances. Sound and presentation match the excellence of the music making.

Copyright © 19 August 2024

Gerald Fenech,

Gzira, Malta