DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

THE MAGNANIMITY OF

MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS

JEFFREY NEIL reflects on a performance of Beethoven's Choral Symphony

As part of a surprise birthday gift, my husband took me to see Beethoven's Symphony No 9 at the San Francisco Symphony last Saturday. The Ninth, unadulterated by other pieces on the program, just the Ninth, was the unexpected, but enthusiastically received interloper. Even as I commemorated another year alive in a world so seemingly overwhelmed by strife and the ascendance of the coarse and the ugly, I was reminded by Michael Tilson Thomas of the 'conspiracy' against dissonance and division at Davies Hall.

MTT conducts Beethoven 9 - publicity from the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra website. Michael Tilson Thomas photo © Brigitte Lacombe

The word 'magnanimity' is what comes to mind when I think of my public and personal experiences with San Francisco's long-time conductor. We shared a personal friend who took me backstage a few times after performances. Maestro Thomas had a long line of colleagues, sycophants, and friends queued up to see him. I found it remarkable that he always remembered me and asked me about what projects I was working on. My own relatively unimportant work was given a sense of importance by his curiosity: this is the essence of magnanimity. Instead of the diva-like scorn or cool indifference I have encountered in other accomplished musicians, the magnanimous maestro sweeps everybody up in his generous spirit; he makes us also desire to be creative and industrious.

When the baritone floods the audience with his warm, enveloping, and inescapable 'O, Freunde!' toward the end of the Ninth, he embraces us in a gesture of magnanimity - one that is sorely missing from the world.

Bass-baritone Dashon Burton, who sang in MTT's Beethoven 9 in San Francisco.

Photo © Tatiana Daubek

In my life, I have found that when people who are great in their fields show an interest and curiosity in me, they invite me to feel as if I were part of their own lofty world. Even if the interaction is just for a few minutes, it has the capacity to elevate and provide direction.

The baritone invites the audience, the orchestra, and the large choir:

O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!

Sondern laßt uns angenehmere anstimmen,

Und freudenvollere.

(Oh, friends, no more of these sounds!

But let us sing more pleasantly,

And more joyful.)

It's not that the music has not been beautiful up until this point or that it has not reached ecstatic heights. These are Beethoven's own words, added to Schiller's poem. The symphony is no longer about entertaining, elevating, or awing. It's about enfolding us - 'all those who are good, all those who are evil' - to move into another register of existence - into the commingling of voices of friendship. It's important to note that the German is simple, not like many English translations. The words are meant to penetrate, not perplex.

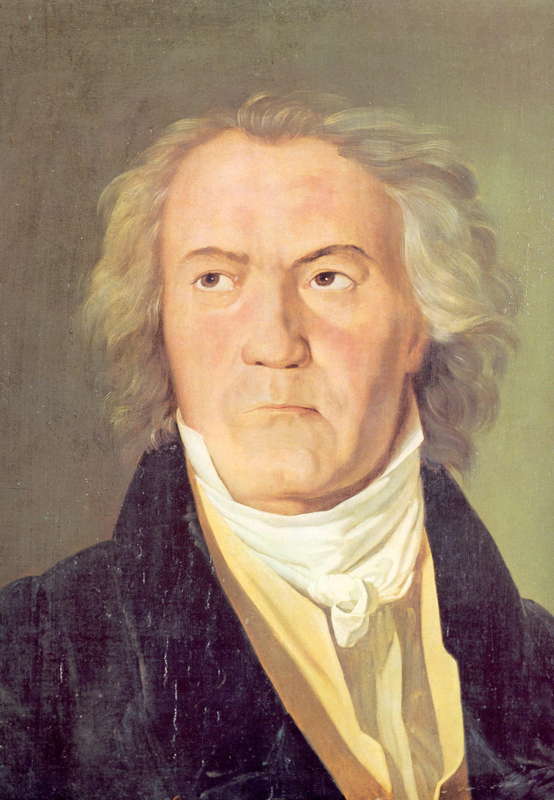

An 1823 oil-on-canvas portrait of

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) by Austrian

painter Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1793-1865)

After his illness, I didn't recognize Mr Thomas when he first walked out. But as he mouthed all the lyrics to the symphony, I could discern the man that I had seen on the stage and backstage. Frail as he seemed, his body was suspended by the meaning of these lyrics. In his parting words to his audience, he spoke of the little 'conspiracy' of bringing together a group of music lovers in San Francisco all these years. The word is perfect in its irony and the clarity of meaning. It is indeed a conspiracy against dissonance and brutality, coarseness and meaninglessness just to come together and listen to classical music.

Michael Tilson Thomas. Photo © Art Streiber

As I consider what values and aspirations I want to take into the latter part of my own life, it is the magnanimous spirit of this conductor's life, this symphony, and especially Beethoven's own words: 'Let us sing more pleasantly, and more joyfully.'

Copyright © 24 October 2023

Jeffrey Neil,

San Francisco Bay Area, California, USA