VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Artificial Intelligence, including contributions from George Coulouris, Michael Stephen Brown, April Fredrick, Adrian Rumson and David Rain.

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Artificial Intelligence, including contributions from George Coulouris, Michael Stephen Brown, April Fredrick, Adrian Rumson and David Rain.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

SPREADING LIGHT AND MAKING DARKNESS VANISH

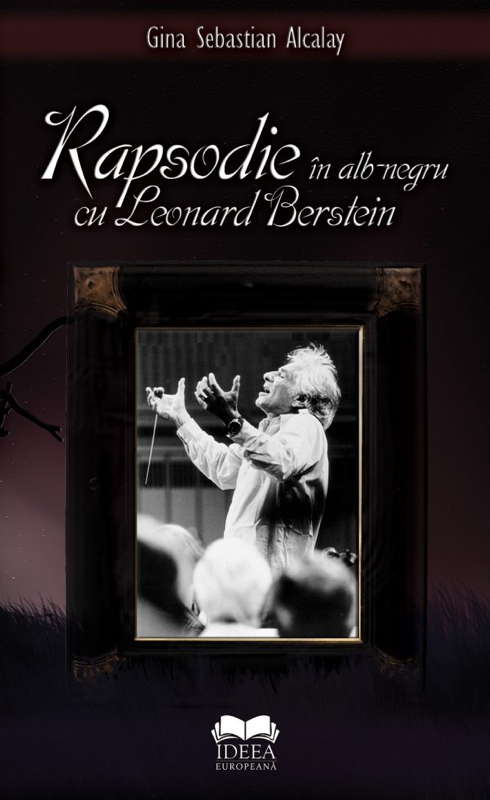

LUIZA CATRINEL MARINESCU remembers her classmate, the Romanian pianist Eugen Alcalay and explores the pianist's mother's book 'Rhapsody in black and white with Leonard Bernstein'

On my way back from Sofia, Christmas Eve 2022, I was riding a cab that passed by a low-rise building once on Nicolae Iorga Street, now Dacia Boulevard in Bucharest, tucked up between Piaţa Romană and the Romanian Academy Library.

Not a particular thought, but when in front of that house, something crossed my mind - Eugen Alcalay, my former mate at High School of Music George Enescu lived here, I wonder what was he up to? ... Got home, Christmas came and went and, despite my intent of not going on the internet, I eventually found out - In Memorium: Eugene Alcalay, DMA, 13 October 1966 - 26 June 2019 - College of the Arts - Azusa Pacific University (apu.edu)

Eugen Alcalay (1966-2019)

Eugen Alcalay was no more. The little genius, his nickname given by his classmates at George Enescu High School in the 1980s, had departed this Earth. He had a tournament in Romania, in Iaşi and, upon his arrival, his soul left him ... Behind, his music on some DVDs to be found on the internet, several recordings uploaded to YouTube and the book written by his mother, Gina Sebastian Alcalay.

Rhapsody in black and white with Leonard Bernstein, the memorialistic novel of Gina Sebastian Alcalay, a Romanian language author, is the portrayal of the price of success paid by a pianist who left Romania during Ceausescu regime, following his crossing paths in Bucharest with some of the greatest personalities in the musical art, such as Sergiu Celibidache and Leonard Bernstein. The author, born in Bacău in 1927, graduate of the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at University of Bucharest, worked as a journalist, translator and English teacher.

Gina Sebastian Alcalay:

O rapsodie în alb şi negru cu Leonard Bernstein

(Rhapsody in black and white with Leonard Bernstein,

Bucharest, Ideea europeană Publishing House, Ideea europeană Library,

Memorii collection, corespondence, diary, 2010)

After Eugen, her son, met Leonard Bernstein, who offered to sponsor and mentor his artistic education in Tel Aviv and America, Gina and her husband, Alexandru Alcalay, arrived in Israel in 1983, to reunite with their son and her mother. Leonard Bernstein, via his solicitor, and a group of 'close' friends suggested their son stay in Tel Aviv for studies. Since most of the contract clauses had not been complied with by Leonard Bernstein's 'friends', the money had run out quickly without reaching the scholarship rightful recipient, and Eugen - the fourteen-year-old having to live on his own, isolated, rejected, famished, looking for shelter in the nursing home where his grandmother was a patient herself, found himself in the impossibility to stick with his study plan and the normal lifestyle stipulated in the contract drafted by Leonard Bernstein's lawyers; therefore his parents are rushing to join him in Tel Aviv and accept the unacceptable, in such some way:

During that year and a half he spent in Tel Aviv, he often found a roof over head in his grandma's house in Beit Avot (nursing home) in the midst of old and ailing people, thus being deprived of the so necessary constancy in piano practice as well of the multiple opportunities provided to other young talents in Israel. 'We also have our own prodigies here!' was the leitmotif always put forward by the then AICF director. In Romania, the young boy had been too Jewish; in Tel Aviv, as it seemed, he was allegedly too Romanian. (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 46)

A member of the Association of Israeli authors of Romanian Language and of the Writers' Union of Romania, Gina Sebastian Alcalay agreed to stay in the Holy Land, kept on writing and teaching English, along with lobbying for her son, and collaborating on publications, such as Viaţa noastră, the later Ultima oră and Jurnalul săptămânii, Minimum, Lumea liberă românească, Izvoare, România literară, Contemporanul Ideea europeană.

Her volumes are Poate mâine, novel, 1994, second edition, revised and completed, with a foreword by Academician Solomon Marcus, 2004; Cei de dincolo, 1996; Pe urmele altora, essays, 1997; Peregrinări, 1997; Singurătatea alergătorului de cursă scurtă, novel, 2003; and Înainte de a fi prea târziu, essays, 2006.

She received the 'Brickman' Award, HOR - Jerusalem; the 'Nicu Palty/Acmeor' Creation Award; the Award of Sara and Haim Ianculovici Foundation, Haifa; Iacob Groper Award, Jerusalem and the 'SION' Award of the Association of Israeli authors of Romanian Language.

The memorialistic novel Rhapsody in black and white with Leonard Bernstein mainly depicts the story of a family of Jewish intellectuals in communist Romania, who had an extremely talented child for the fascinating world of music, in whose creative potential they fully believe, hence supporting him financially, morally and sacrificing themselves for his sake, post-factum asking themselves questions on the decisions they had made - people feeling remorseful for the fact that they let live away at fourteen that child they gave birth to and who, although far from them, as gifted with common sense and a distinguished education received from parents, found his way in the international musical world, like a rare flower with exceptional traits blooming in less known places in the Amazonian jungle (which is not actually Amazonian, but Romanian).

The career of a musician in Romania during the last years of the communist dictatorship was a matter of chance, which Eugen's mother exploited the best possible in favor of the young pianist and composer, who before anything else needed diplomas from prestigious institutions in the Western world, a recognized education, doors to open, classmates to make friends with and work together. Like all the students at High School of Music George Enescu, she also believed in the story of Maestro George Enescu and his disciples, the young Dinu Lipatti, the famous Yehudi Menuhin - yet, no one had told them what the maestro had gone through where he had taken refuge, for fear of communism.

Piano players would be assigned one seat at the National University of Music Bucharest every two years. The assignment of the graduates meant teaching music and physical education in middle schools in the Romanian Plain, with no beginnings or ends. Consequently, sooner or later, students were either staying or fleeing anywhere they could, hoping to resume their careers. It was rather difficult for a piano player, as the absence of the instrument was a real challenge. The players on string, wind instruments or percussionists had it easier when employed by more or less known orchestras in the western countries. All of the above were part of a dime musician's life in the 1980s when I was born. There was no long-term marketing strategy for these educated, talented, childhoodless students. In practice, a pianist had to be financially self-supporting for a long time - they might reach an international status in their late thirties or early forties. As for the female piano players, there was no gender ideology - you were told, in your face, that Schumann was successful, unlike Clara Schumann.

The 1980s generation of pianists in Romania was looking up at national and international musicians, seasoned such as Arthur Rubinstein, Arturo Benedetto Michelangeli, Florica Musicescu, Cella Delavrancea, Aldo Ciccolini and Sofia Cosma, as well as younger ones, eg Radu Lupu, Valentin Gheorghiu, Dan Grigore, Sviatoslav Richter and also prodigies - Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, George Enescu, Dinu Lipatti, Mihaela Ursuleasa. Very little was told to the little pianists and their parents about how much effort should be put into this profession and how selection was made, what their real chances of affirmation were, how able-bodied and well fed piano players should be, financially and spiritually, in order to be able to ride out their training while showing discipline to the point of exhaustion. Nor were they explained what exhaustion meant for a prodigy from the perspective of the other aspects in their life, or that the hasting of the professional pace in the absence of the emotional and intellectual growth would turn them into failed young people in their thirties.

The pianist's maturity is a lengthy process, at times never completed, strewn with apathy, such as coming down from the concert stage to the classroom, to teach piano to pupils, without ever grasping the learning psychology or the music pedagogy. The teachers were sick with rat racing as ever, to prove themselves through their students - and for that purpose they were doing exactly how they had been taught to, for a fast performance. Unaware of the consequences, parents, most of them ignorant, were supporting the actions always depicted as to tame the 'louts' (who wanted to play - as Haydn's baroque sonatas, the album for Ana Magdalena Bach and Clementi's sonatinas for six- to ten-year-olds, Czerny's virtuosity exercises or Hannon's piano technical exercises were taking away their playtime!!!)

The role of the families well connected in the world to lobby for their children, to do marketing for the outstanding, unique, more-than-educated product they were offering and to provide the young musician with the status of living independently for the stage life was paramount. Parents would not communicate among themselves, children were taught to watch, obey and be quiet, not to share their plans, what they are studying, what competition they are going for next. Hence, the role of manager assumed by the mother who will risk everything to make her son known.

When the boy was 11-12 years old, Sergiu Celibidache came to Bucharest for a string of concerts with the George Enescu Philarmonic, a musical event that gripped the entire city. Celibidache himself, more elated than ever, seemed to be caught in a rush of musical patriotism, or maybe because he had seen in the young Romanian musicians a certain receptivity, obedience, thirst to learn and mostly a personal reverence that were scarcely shown abroad, despite his widely recognized genius. (...) a friend he had met as a young musician in Iasi (they used to play in Macabi soccer team) told him about the twelve-year-old pianist and composer and asked Sergiu to meet the child.

All Celibidache rehearsals were open to the public and the whole of Bucharest came to see them. We were there, every morning, carrying a small suitcase with scores, waiting restlessly during the rehearsals. When would be the best time to go to the Maestro? Is he going to welcome us? Every time we left the house, the boy promised to go and meet him, but once in the music hall, he would start trembling and all of his courage was draining from him.

Eventually, at the end of one rehearsal, someone who knew the managing director of the Atheneum practically pushed him from behind to go into Celibidache's room. The boy handed him the compositions, talked for a while. Celibidache was just getting ready to leave, as imposing and massive he was in his shaggy-haired coat - the boy, like the lamb facing the big wolf; he was getting more and more relaxed, happier, vivacious; and the Maestro was not even close to that strict and hard-to-please educator as he had seemed on the stage when scolding one of the orchestra members, but a charming gentleman who was speaking the same language as he was. They agreed to meet again (to find out what the Maestro thought about his compositions) and walked out together, followed by hordes of people who were still frenetically shouting their adoration to the conductor.

P1 (the then head of piano department at G Enescu High School, named L M) was also among the onlookers in the main hall of the Atheneum - it was at that time when Eugen was roaming the roads to her house for private lessons, yet for nothing - barely greeted us back. Instead, she blasted over the phone on the same afternoon. 'What were you doing over there? I was, too, but I didn't go to bother him!' 'We thought it would be good for our son's future to meet the Maestro ... You know, he is offering those great summer courses in Triers, scholarships for some ...' I was stammering, trying to justify myself - it is the first time we are introducing him to a famous artist, just wanted to know which way to go ... And she, a teacher at the peak of her career, was putting herself on the same footing with the pupil at a turning point in his life, blustering against the 'ones of our kind' (not like her, but like us) who are always trying to make a profit.'

'Let me introduce to you a young Romanian composer', Celibidache told the orchestra members, before asking the boy to play his own compositions on the piano when they met a second time. And after that, 'I am going to teach you how to compose without the piano,only in your head, at your desk. When I come back here, stick close to me, wherever I go, you come.'

'So, should we go right ahead and let him pursue music?' 'By all means, on one condition, though - to have good teachers and commonsensical parents. My father left me to my own devices - he was a brilliant guy - I was coming from playing soccer, my clothes torn, no one told me otherwise! Let him live like the other kids, even if his throat hurts ... or his tummy.'

'How do you know, Maestro?'

'That's what happens with these super-talented children. Yes, you heard me well, he is a super-talent. And don't forget - make him eat a lot of garlic.'

Celibidache had a son himself, whom he adored. It was much easier to meet him and talk about the future of our son than with P1. She - well-informed as always - told the story as how her parents asked Maestro to predict whether he was going to have a career in music and he rebuked them all three ... (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 32-34)

I had known Eugen Alcalay since kindergarden. I think I was six when I saw him first, on a September day, 1972. One day, at the kindergarden in the yard of Precupetii Noi Church - the same place of the parochial house where father Gheorghe Holbea was holding his conferences - at the entrance to that kindergarden was a woman who was telling my teacher then, Mrs Pacioca, about her little one whom she had brought there to get him used to being around children. She was Mrs Alcalay, Eugen's mother. Mrs Pacioca, the lady with a name of a Portuguese-Brazilian candy - Paçoca is a dessert made of crushed peanuts, salt and sugar, for 24 June, Saint John's Day - was a gentle teacher, a wonderful human being, considerate towards children as if they were one of her four at home.

Back then, Eugen Alcalay was a fragile child with blue eyes, a pure and innocent smile, and blonde curly hair like a porcelain doll. He was a skinny kid, short, rather scared as are all children coming to kindergarden for the first time, not knowing anyone, who blush and keep quiet when you are asking them something - they are ashamed to answer, lower their eyes, turn their head away as if they did not know you and really have no clue why you are interested in their name. But after that, they would look out of the corner of their eye to see whether you left or not? Are you still looking at them? He was so cute when he smiled.

Eugen's mother was showing our teacher his notebook with drawings and telling her how beautifully the little one was playing. I passed by them, overheard their discussion and I thought why my mom did not show her my drawing notebooks or that dad had taken me to piano lessons. Dad was telling me that I would never be alone if I knew to play the piano. Back then, I was playing all the time, from the bottom of my heart, all the pop music songs on the radio. When they heard how easily I was playing, they asked me to conduct the children's choir in kindergarden, for a school play. Moreover, my parents enrolled me in the piano lessons at Central House of the Army, where a kind, older teacher, Mrs Marinescu, was teaching us piano by the method of Maria Cernodoveanu. Dana Ciocarlie was also a student there. Dad was taking me to that place twice a week. At home, I had a carton keyboard my dad had made on which I was repeating what I had learned. I was a regular child who was learning willingly, easily and happily. The music school I attended made me want to stop playing ... for good.

Eugen's mother, Gina Sebastian Alcalay, recounts and captures the curious atmosphere our parents were living, taking a refuge in the pleasure to teach their children Truth, Beauty and Goodness:

I was trying to forget, as much as possible, what was going on around me while raising my little boy with a total and exclusive dedication, made even more arduous and fanatic with the discovery of his premature talent. So many things were to be done for that little chubby, with his staring blue eyes, wide open to the world, dimples in his cheeks and in the back of his hands, blonde curly hair, plump lips slightly turned down into an angelic smile or a laughter gurgling like a mountain stream, with his short and flabby fingers that were melding one song after another. (Sebastian, Alcalay, 2010: 19, 20)

Eugen Alcalay's maternal grandmother was a piano teacher. She was the one to discover the talent and passion for music of her grandson, the delicate Cri, as they were calling him at home - they understood the imagination and creativity the child was displaying in his game with the piano sounds. His mother dedicated herself completely to his upbringing and healthcare, primarily.

Between Eugen's health concerns - he was incredibly feeble from his first years of life into his teens - and his out-of-this-world gift, my larval fervor exclusively focused one way spewed to the outer consciousness, hurtling with an explosive violence any other urges - either new literary ventures during the so-called thaw years, flirting and love fantasies, or going up the career ladder. (In fact, I have always loathed the well-oiled tongued creeping into everyone's favor, sponging on others, working themselves up to a post and the career schemers; maybe because I had gone back to work then, these were, with rare exceptions, the only ways of social climbing.) (Sebastian, Alcalay, 2010: 21)

Time passed by. I took the entrance exam to the High School of Music George Enescu, a seventh grader in 1979-1980. I was studying piano, one of the twenty others students, in eager rivalry in a music school. I honestly believed that there were only four types of teachers - Jewish, Armenian, Hungarian and Gypsy - lautari/fiddlers call themselves as such - as students were assigned to a teacher of similar ethnicity. The Romanians would go anywhere available places were. Piano: step**** was written on my student card in the first grade. In that school, I learned to stop saying I liked playing, did not matter how good you were unless you had connections and money; parents were told from the get-go that the school was not free, but rather expensive. For me, my primary teacher became the model of what not to do as a teacher, especially at the end of the fourth grade when she scolded me because my parents had sent me with a bouquet of flowers on the last day of school.

As for the music teachers, most of them had no clue about musical pedagogy, child or teen psychology - they would employ pavlovian methods, crude, of trial and error, which were turning the instruments lessons into a sure ordeal, in most cases. We also had lessons on Saturday afternoons, twice a month. Sometimes, they would call us to school on Sunday, too. We were little children, yet our school schedule had six hours of general knowledge and six hours of daily instrument training. We were working twelve hours per day and, in the morning, we would be back for more as nothing happened. The only teacher who was behaving nicely during the music classes was the choir teacher. During a musical tour in Timişoara, he gave us lemons and honey before going on the stage, after he saw how we looked like. It was when the food was rationed in Bucharest, with people waiting in long lines. Only after the Revolution, I found out that the teacher was an Orthodox priest.

There were teachers who had brought their children to this school, enrolling in their classes to mold them academically - Alexandru Tomescu is one of the examples. In those years, his soul fabric, of gift and grace, was weaving with the music sounds in the high school where his mother, Mihaela Tomescu, was a violin teacher and his father, Adrian Tomescu was teaching piano. He was getting ready to come into the world and enjoy his life as a prodigy, awarded at eight with the 'Citta di Stresa' absolute first prize in Stresa, Italy - a prodigy educated by his musician parents, whom I followed fondly, as I had imagined who he was, before he was born ...

There were fewer students in our class. Many of them had dropped, others left for America. Oana Moucha, my best friend, had left to New York with her parents and would become a general medicine doctor, like her parents - Oana Patricia Moucha-Hantar, MD at NewYork-Presbyterian Medical Group Westchester - Primary Care & Specialty Care: Internal Medicine | New York-Presbyterian Doctor in Eastchester, NY (nyp.org). Stavros Deligiorgis's daughters were here - he is the Romanian translator of Greek background, born in Sulina, the author of anthology - Ioana Deligiorgis was the co-author - titled 100 years of Romanian Poetry bilingual series, published in Iasi, Junimea Publishing House in 1982, and Katerina, the younger daughter, is a comparative literature teacher, expert in German idealism and Kant's and Kegel's philosophy (Katerina Deligiorgi : University of Sussex.)

Students from Ardeal were there, for wind instruments, bassoon and trumpet. Two boys had maximum grades in the piano classes. One of them would be the Rector of the National University of Music and the other one, Eugen Alcalay, was sent to our class, in A. We were living in an extraordinary time - we were running during breaks like chickens with our heads off, as we did not have any time for play at home. Apart from the short TV program, they broadcast How to understand music every Sunday morning, at ten, with Leonard Bernstein. He was an outstanding music teacher whom you would just listen to with no bore, as he was smiling, explaining things clearly, no yelling. In the meantime, my mom had bought me How to understand music by Leonard Bernstein, a book we could hardly find, as it was not published by Editura Muzicala, Bucharest until 1982.

At the Romanian Atheneum, Sergiu Celibidache had held rehearsals open to the public, where we went while playing truant two days in a row (with the approval from the teachers on those days). According to the author of the memorialistic novel, malice had started. Eugen was permanently condescended to by some classmates, not academically bright, ear players, as the taraf people were called:

My heart was breaking to see him with tummy aches, when he was afraid to be left home alone, when he was coming back home, horrified by the brutes in his class. I hated Mrs P1, the head of piano department at George Enescu High School, the bête noir of Cri's childhood - she was scoffing and humiliating him in every way possible: I was happy for his happiness, elated to see him next to me, at all times - I had taken a much earlier retirement, just for him - the two of us together - meals, playtime, trips around the country, gardens, skating rink, swimming, piano lessons ... (...) my entire universe was called Cri and Cri had to be taken out of the country. Everything is so tangled and important as well! (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 51)

Some good-for-nothings in his class had nicknamed him 'the little genius', actually repeating as parrots what they had heard their teachers say. Eugen didn't react, but he was upset. I was asking myself why they had to pick a bone with him? They were studying string instruments, not the piano. The answers to my questions back then are coming now, in the book written by his mother.

We would have recitals every trimester, graded very closely, thus leading to animosity and a fierce competition among the pianists. There were music contests and only the chosen from among the best would go there, in the country and abroad. The sponsors for these trips, students and teachers, were of course the parents of some, well connected and wealthy. The music high school had three categories of students - modest families, average and above average. The value hierarchies of the children's work were simply turning upside down the social and economic ranking of their parents, who were doing what they knew had to be done to support their children, some of them tone deaf who would graduate just on the line.

Such hierarchies were kept within the walls of the school. Outside of it, still the money and connections were the motto. In general knowledge classes, we had really good teachers - we were able to learn everything in school and did our homework during the breaks, after every class as we had no time at home for that, due to the instrument training. We would have great results in the Maths and Romanian language olympiads up to the city round easily, to the amazement of our instrumental teachers. They were surprised; moreover, they were humiliating us telling that we cheated in our description of the piano piece we had for homework, but what they did not figure out was that we could visualize the music, that music was moulding our verbal intelligence and expressivity; they simply did not understand that the phrasing, breathing and the nuances of our repertoire were building musical paintings in our minds that we were able to convey through the manuality and fingering skill trained via the pavlovian principles of the Russian school, the alma mater of most of our teachers.

Gina Sebastian Alcalay's book is a miniature fresco of the Romanian music schools in Bucharest during the last-but-one decade of the communist regime, the competition among teachers for students, students among themselves, the politicized national festivals and the attempts to resist through culture, classical music. (The National University of Music in Bucharest would only open only one seat for piano every two years.) The music to be studied was West European, pre-classical, romantic, modern and, of course, Russian. The repertoires of all the students included Romanian music, mandatory for the trimester auditions. The music sheets were relatively easy to procure, as they could be found at Muzica store, coming from East German sources. Sometimes, those sheets were copied manually, as there were no scanners or xerox machines. The teachers themselves were writing them by hand - for instance, Gershwin's music - the arrangement for piano and choir of the Rhapsody in Blue could be made for the choir, with Constantin Sandu (an eleventh grade student) playing the piano.

The students at George Enescu High School were studying theory and solfège starting in the primary years. Later, in junior high, choir classes were added, plus listening and understanding of musical structures. The only lessons when the little musicians were asked to work together were the orchestra and choir. The students of wind, string and percussion instruments attended the orchestra classes - the conductor was a teacher who really had to keep a tight rein on all the energy of young teens, talented yet challenging, most of the time. Coercive means were never in short supply - he was infamous for his rampage, but famous for his concerts. There was a taraf of students, leaving abroad quite often, being looked at the same way the cultured European music would at Roma music - with envy and frustration. The choir classes were mostly aimed at the piano students, trying to build a certain harmony among young people trained separately (different instruments), who would congregate during the theory and general knowledge classes but missing the opportunity to sing, listen and play together, as a whole. The choir for equal voices was called Viva la Musica!

I truly believe that each of us is carrying in our very innermost space some quiet universes labeled 'past', which can be brought back miraculously into the present by an image in a movie, a line in a book or an object you thought lost forever. For me, no matter how curious it seems, the word 'go' had such a catalytic role ...

'Go!' - the choir teacher would say it to my son, when the voice was lagging less than a semitone. The same choir teacher, who would postpone indefinitely to schedule my son's compositions, teased him unmercifully for every absence from his dreary rehearsals - and for most students, totally useless.

'Go!', the piano teachers would say ... (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 21, 22, 23)

Go! - that meant you had to be on guard, to join the choir, to get your voice ready, to follow the tune closely, to match with the keys on the sheet. Go! means here and now.

Music history was studied in high school; nevertheless, short introductions were made any time a composer was to be looked into, for a student in the primary years. The instrument teacher had a special correspondence notebook meant to reach the parents, in which there were explained the student progress and the study methods - types of exercises, etc. The school lessons were followed in private, for a charge, with the school teacher or others recommended - teachers, friends, former students.

For me, among all these people, the only patient person I could talk to was Miss Elena, freshman in the National University of Music - she would give clear answers to the questions I was asking. At the end of the eighth grade, it was mandatory to attend the trimester audition, for my final yearly average, even if I had not been tutored for piano or theoretical knowledge. I had ten in theory and came on second after my piano performance, after a classmate of mine, Aladár Rácz. My teacher, who could not believe my result, curiously asked me who my tutor was - when I told her that I had done it on my own, she called me a liar, as she would usually do. In music, the idea is that the energy transfers from a teacher to students play an essential role to build the disciple's personality and self confidence. What Mrs Alcalay writes about the teachers who tutored her son and had no clue about one another was part of the winning strategy, which avoided fights, airs and graces on part of the teachers who would feel offended if you went to another educator to learn the craft.

In 1982, before going to Israel to meet Leonard Bernstein, upon his invitation, my son had three private piano teachers and one school teacher. No one knew about the others. And I would hear in every lesson, 'Go!' (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 35)

Gina Sebastian Alcalay's book captures the general feeling between the then head of the piano department and the other teachers, more or less young, the attitude towards the preferred students - or disliked - and understood that the school prepared mediocre musicians, with no prospects. She is the one who chose the best path for her son. Eugen Alcalay was a child, shy and introvert, purely horrified when he became the observed of all the observers. He would become clumsy, flustered, shaking, even when he was praised for the accuracy in the musical dictation, for example. He would hear and write music perfectly.

There are two voices in Gina Sebastian Alcalay's memorialistic novel - the mother's and that of the 'boy', which shows to a certain extent the distancing and her influence upon the later psychology of the mature pianist, who grew up among strangers starting with fourteen years of age, due to some hard to anticipate circumstances, impossible to live through and get over.

Eugen Alcalay lived as a stateless person in America and his status was cleared only after the Revolution, when Leonard Bernstein passed away in 1990. As a refugee, he lived under the poverty line after Bernstein's heirs cut off his grant exactly during his junior year in college. That time of extreme need, humiliation in a country where he had no rights, albeit living there since he was fourteen, the Jewish professors who were 'antisemitic' themselves, Leonard Bernstein's friends in Israel who stopped his financial aid, thus breaking their promise made to Eugen Alcalay are proof of lack of benevolence. It is quite unimaginable for you not to understand that the novel is actually a memorialistic crisis, where the mother keeps asking herself whether she did the right thing or not. Except that the reader is not allowed to judge, but only to accept, listen, learn and make a choice.

To confirm that the meeting with Leonard Bernstein that changed Eugen Alcalay and his family's destiny has always been a choice, the author writes:

In this book, I have used, with the necessary adjustments, various fragments in my novel Singurătatea alergătorului de cursă scurtă (The loneliness of the short race runner), in a different format than a transfiguration from the literary fiction. (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 4)

The theme is thus recurrent, since it has not reached its solution. The memorialistic fabric provides a glimpse of Eugen's mother's own childhood in Bacău, during the ugly years of deportation when:

People were saying she was smart, yet she secretly wanted to be told she was beautiful.

Maybe she just wanted to prove her mother wrong when she used to tell her all her life, repeatedly:

You are not beautiful, watch what you're doing! (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 12)

Past her prime quickly, Eugen is a gift for her, the author of these stories and his mother. Life with Eugen is changed through the fated, ominous word. 'The boy' is the sun of the family microcosmos. The mother will use the word 'music' around him as a true fairy. 'The boy' will become the purpose of her universe.

He will become my masterpiece. (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 14)

The magical word, music, will make an entire world resonate.

Now I remember how proud and happy I was, when seeking refuge in the family microcosmos, I heard Eugen (or Cri, his pet name because of his cooing like a relentless cricket and also of his too frequent screams) first cheerful squeaking, more like a longer yip in successive melodic trills while the radio was playing a piece by Chopin. 'He's going to love music, mind my words', said my mother, a piano teacher, picking the baby up and bouncing him a few times.

When he was three, I sat him at the piano; he was already composing short songs at five to six years of age, whose names I would make up - Mother, End of holiday, later - Theme with variations, Fantasy with bells, and more others. (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 17-18)

Gina Sebastian Alcalay's book is also an illustration of the price of success for a pianist, composer and teacher, for a mother who was always concerned with her son's career in its early years, a career that was difficult, if not impossible to fulfill in communist Romania or even afterwards.

1 October 1999

I have been left completely alone. All my loved ones, Alexandru (died in 1994), Lenny, now Remy, too (and the charms of his beloved Paris) are no longer with me. With Cri, now farther and farther from me, I feel, more than ever, abandoned, ready to turn myself into an inert magma. I grew a goiter of tears. (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 265)

The first person voice of this novel is Cri's, the honest artist with a backbone, striving and toiling to graduate with flying colors from all the courses in the famous music schools where Leonard Bernstein had sponsored him to attend, going all out to finish what he had started even if he had been left with no financial means and country, in the aftermath of Leonard Bernstein's demise, on 14 September 1990.

Modesty is in fact the forgotten virtue, the sign of the elect souls. Eugen Alcalay is an example of a memorialistic character who helps us understand that years are needed to comprehend how meaningful minutes are. That between your conscience and reputation, it is esential to make sense of your conscience. Your reputation, what others think about you, 'it's their problem'. Eugen Alcalay's innate modesty, gentleness and spirit finesse, which I had noticed when he was in school, is the perfect demonstration of the art, goodness and truth in whose spirit he was educated. He never reacted when insulted, only had a sad look in his eyes. He was trying not to get smeared or to besmirch anyone. He seems to be writing a letter to his mother and the words validate the maturity of his options as an artist:

'Mom, people may not think of me as very smart - for you to flaunt your intelligence in front of anyone, by tensing up all your brain potential in any moment, like the athletes bombing their chest to brag about their muscles, it ultimately seems to me one of the greatest sins of vanity, similar with chasing glory, in comparison with the tens of thousands of artists more famous than you, while millions and billions of people never did or ever will hear about you?

'Even if I might be wrong, it seems a good argument for your intelligence to play the idiot once in a while - when needed, in other words - just to avoid hostility, fierce rivalry, envy and dangers of all kinds lurking around those who are visibly craving to reach the top of the pyramid. They are wearing themselves out to a frazzle while still young, they are burning out too soon and later in life they are incapable of giving anything to mankind. And, of course, I don't mean certain notable exceptions, Mozart or Goethe like artists, but rather regular young people like me, who Lenny wrongfully labeled as geniuses, making their parents and friends expect God knows what phenomenal things from us.

'I am aware that you, ill-advised as you were by him, blanketed your soul with illusions and had great expectations from me, while chanelling all your unfulfilled ambitions towards me. But I also know that, whilst not letting myself be disrupted and influenced by anything not close enough to my visceral nature (your and Lenny's desire for me to become a famous composer and conductor), I went my own way, slowly but surely, and here I am, today, got to smooth water ... (...) Mom, let's not get us deceived - no matter how happy the circumstances are, they cannot make us other than what we are. You thought I was a Radu Lupu. I am not.' (Sebastian Alcalay, 2010: 218-219)

Eugen Alcalay is the piano music he created by playing it, spreading light and making darkness vanish on its own. His destiny proves we cannot stop the wind, yet we can trim the sails. If you are born with wings, you have to learn in life how to rise above what others think and fly confidently to the world of your imagination that will turn into reality. Eugen Alcalay lived himself the change he wanted to witness in the world through music and convinced everyone that you arrive nowhere without having a dream.

Copyright © 30 August 2023

Luiza Catrinel Marinescu,

Bucharest, Romania