SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Beautifully Apt - Choral music by Herbert Howells, heard by Robert Anderson.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Beautifully Apt - Choral music by Herbert Howells, heard by Robert Anderson.

All sponsored features >>

A hundred not out

Today sees the twentieth instalment of this venture in its present mutation and as each salvo consists of five composers even the most mathematically-challenged won't need too long to figure out that that means that since New Year's Day - with today included - one hundred composers have had their chance to shine here, even more if you factor in what I wrote last year.

The fact that there are still hundreds more wonderful composers and compositions that I haven't as yet found the means to do any kind of justice to just shows the fertility of the soil of oblivion and how resounding the echoes here are. In order to keep it up and keep them coming and to keep things stimulating for myself as much as anyone else I feel I am going to have to change my position somewhat. I don't know what that change will be but there will be no let up in what you have come to expect.

1: Matthijs Vermeulen (1888-1967):

Cello Sonata No 1 (1918)

Not long before Christmas last year I attended a concert by a very young Italian duo. Young they may have been but both pianist Valentina Gabrieli and cellist Emanuele Rigamonti showed no lack of mature talent and abundant charisma. As much as I was impressed by their combined musical ability it was an equal pleasure to see their commitment to unusual programming.

Pianist Valentina Gabrieli and cellist Emanuele Rigamonti

I attend concerts by a lot of young musicians and I have to say it is depressing how similar so many of the programmes which they offer to their listeners tend to be, as if the conservatories are churning out factory-produced musicians who display little individuality in what they choose - and presumably in what they want - to play.

For these reasons when I spoke to Valentina and Emanuele after their concert it was heartwarming to listen to them telling me that a lot of typical music of the eighteenth or nineteenth century doesn't say anything to them. The music of the twentieth century or today is what really excites them and what they love to play the most, especially great music that audiences are not used to being given a chance to hear.

Talking about the repertoire they play I asked them if they knew or played this piece, or Matthijs Vermeulen's second sonata for similar forces. They weren't aware of this music but they gladly took note of my suggestion and I really hope they have investigated this wonderful sonata - and its twin - since, as I feel it suits them perfectly. I say that not being a cellist nor a pianist, so I have no idea of the technical challenges involved. My suspicion is that they are quite considerable. All the more fun to surmount and subdue, even more so as they have youth on their side.

The liner notes for my recording of this piece are wonderful in their withering statements about complacency, mediocrity and provincialism, all things that Vermeulen was never guilty of but because of which he was regularly made to suffer. The writer of the liner notes sees as particularly Dutch how genuinely talented and original composers are ostracised while their peers of lesser talent that slavishly copy the latest imported fashions from fashionable places are lionised. Sadly, true as this state of affairs is there is nothing particularly Dutch about it; it happens in too many places.

This is a simply magical piece. The fact that there are only two instruments gives us a chance to hear with more transparency that usual Vermeulen's exhilarating but often maddeningly complex contrapuntal symphonic writing. I don't know if the year of composition has anything to do with the mood of the first movement, in which case it could be viewed as a brooding elegy but to me it sounds just as much of a luscious langourously intoxicated dreamworld.

The second assez vite movement couldn't be of greater contrast. Notes spill out of the score and on to the floor as the instruments are treated to a severe thrashing until the assez lent feel and that Debussyian dreamscale on the piano of the opening movement finally brings us back full circle. If anyone is new to the genius that was Matthijs Vermeulen I can't think of a better place to start than this passionately prescient sonata for cello and piano.

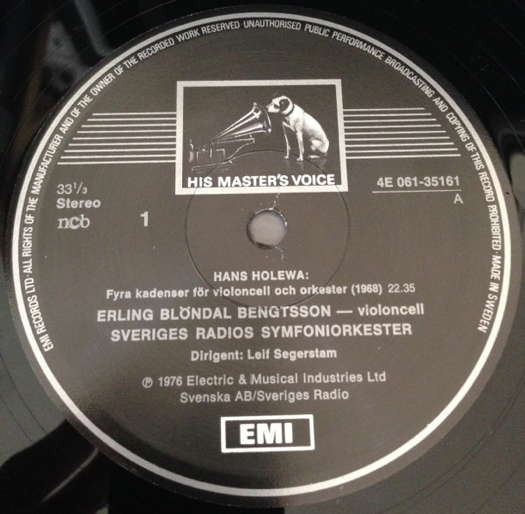

2: Hans Holewa (1905-91):

Four Cadenze (1968)

Displays of purely technical virtuosity for me pale beside those of compositional or imaginative virtuosity, indeed at their most self-indulgent level I find them extremely distasteful and literally hard to stomach. With that in mind it shouldn't come as much of a surprise to know that in general I am not fond of concertos. There are exceptions but too often the fascinating spectacle of integrated musical argument has to suffer at the behest of the empty spectacle of individual technical skill. This cello concerto - in all but name - is one of those exceptions.

Hans Holewa came to manhood in the unique crucible of interwar Vienna but being Jewish he was faced in the 1930s with the stark choice of trying to escape from his homeland or almost certain murder by the benighted Herrenrasse. In Holewa's case he managed to get to Sweden where he and his wife remained for the rest of their lives.

I don't know if it's apt to say that in Sweden Holewa was a big fish in a small pond but he was certainly a fish out of water. His modern musical ideas were not well received in his culturally conservative new home and later on he had to suffer the irony of being seen as out of touch for remaining true to his principles when the avant-garde bandwagon raucously rolled into town in the 1960s.

Hans Holewa: Fyra kadenser för violoncell och orkester (1968). © 1976 EMI

This piece is from the 1960s: whether it's avant-garde or not I will leave that for you to decide but for me it's nothing but Holewa. The fact that he chose the most brazen boast of any concerto: the cadenza, as the central focus of this work is all the more impressive as nothing the soloist does is of any more interest or import than what goes on between the cello and the orchestra or what the orchestra gets up to on its own. The level of integration of idea and execution is fantastically subtle and supple. Indeed this for me is as much a concerto for composer and orchestra as it is a concerto for cello and orchestra.

3: Jaroslav Krček (born 1939):

Symphony No 1, Opus 40 (1974)

Ceremuga, Krček. © 1979 Supraphon

I came to this piece for the first time knowing nothing about it nor its composer. As blissfully happens sometimes with such encounters I was completely bowled over. It puts you in a trance from the beginning. Jaroslav Krček turns the entire orchestra into a throbbing gong. Wisps of vaguely remembered melodies float in and out. The woodwind writing recalls Stravinsky at his most poetically pagan.

As a one movement piece it passes through various moods and tempi. The middle section witnesses a haunting passage for solo harp gradually joined by the rest of the orchestra. Looking at the cover of this album I am set daydreaming of a wonderful world in which clouds sound like this symphony and not like Ludovico Einaudi's soon-to-be released seven CD soporific sledgehammer of insipidness.

4: Malcolm Lipkin (1932-2017)

Piano Sonata No 6 (2002)

Malcolm Lipkin: Piano Music. Nathan Williamson, piano.

© 2023 Lyrita Recorded Edition

I don't believe any of my other esteemed colleagues here at Classical Music Daily - that's right folks, classical music coming at you from all angles morning, noon and night - have as yet reviewed this recent welcome release. This piece firstly comes as blessed relief to hear that in the twenty-first century there are (or in Malcolm Lipkin's case now were) still composers who feel that the piano is valid for anything other than Einaudisms or the most vacuously predictable of soundtracks for the most vacuously predictable movies.

Until I listened to this piece and the rest of the disc I had only known Lipkin through his symphonies but he seems a natural at writing for the piano. This so called 'Fantasy Sonata' is a one movement piece that could have been written a century ago. As I listened to its rhythmic development and harmonic progessions I was reminded of the three Bs: Berg, Bartók and Bridge. No revolutions here but nonetheless enjoyable and worthwhile for all that.

5: Liana Alexandra (1947-2011)

Symphony No 2 (1978)

Liana Alexandra: simphony nr 2, 'anthems'; simphony nr 3, 'diachronics'.

© 1983 Electrecord

I have read Liana Alexandra's music being described with such terrifying words as neoromantic, simplicity, clarity and worst of all accessibility. As regards musicmaking; why anyone after studying the enormously complex subject of musical composition for years and years (and subsequently spending further time trying to hone their craft in an attempt to find the most precious and beautifully human thing about any artist: their unique voice) seemingly doesn't want to do anything more than make music that is immediately and simplistically accessible to all and sounds basically identical to so many other people's music, is enormously disappointing and very hard to comprehend.

Should any of those terrifying words above make you think that from Liana Alexandra you can expect to hear brainless slow tempo minimalist soundtrack porridge, think again. In this absolute masterpiece one may find melodic ideas that possibly could be described as accessible or neoromantic (whatever that means; when did romance go out of fashion?) but if so they make up only a very small part of what is going on here.

Her unique sense of form and orchestration are breathtaking. The confidence with which the music sweeps through its various shapes and sections without the slightest hint of stitching is masterful. Her idiosyncratic harmonic thinking is radiantly beautiful. The distance travelled and the kaleidoscopic range of colours that bloom throughout the orchestra speak volumes as to her compositional skill and extraordinarily rich musical imagination. This music is the unique creation of Liana Alexandra and it sounds like nothing else I have ever heard. Amen to that.

Copyright © 14 May 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain