- Howard Smith

- Nancy Van de Vate

- Ian Bostridge

- Duncan Druce

- Aussies

- Bernard Zaslav

- Olivia Clarke

- Byzantium

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

Bold and Resolute

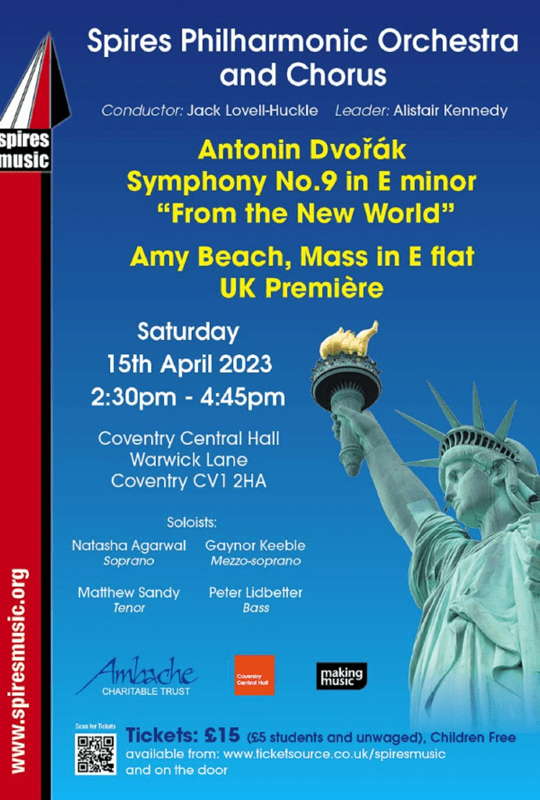

RODERIC DUNNETT is impressed by a performance of Amy Beach's Mass in E flat

The latest concert by The Spires Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus, now best known as Spires Music, and hailing from the famed cathedral city of Coventry, was a highlight of this whole season's choral events throughout England.

Not primarily for Antonín Dvořák's Ninth Symphony, 'From the New World', of which this definitely first-rate orchestra gave a frankly terrific reading, occasioned by the fusing of audibly high-level players with the first-rate, endlessly perceptive and well-communicated conducting of Jack Lovell-Huckle, whose accolades include work with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Welsh National Opera and Scottish Opera.

Including Dvořák's magnetising Eighth Symphony in April 2022, and No 7 in 2019, he has led the ensemble for the past eight years with acuity and insight, and above all a most intensive grasp of each score, revealing detail and insight - with an astonishing and at times unusual freshness - into the works he and his competent management board have had the courage to programme.

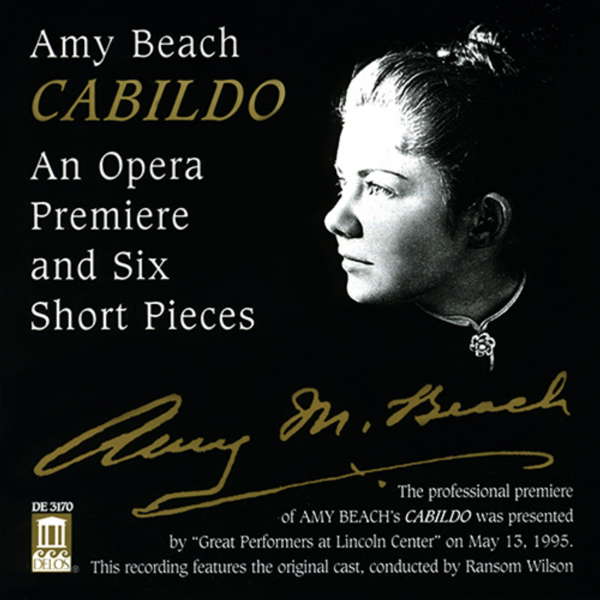

Spires Music's programme for the

15 April 2023 concert reviewed here.

The tenor soloist was in fact Ed Harrisson.

What is their aspiration, indeed their policy? 'We love to uncover pieces of music for chorus and orchestra that have lain untouched, waiting for us to breathe new life into them. We are acoustic adventurers, seeking out unheard gems, and programming them alongside classics we know and love.'

Spires Philharmonic Orchestra & Chorus (Spires Music) pictured in front of the John Piper window and the west window of Coventry Cathedral

Well, having been one of the few choral societies to alight upon Schubert's A flat Mass - Nos 1-3, the F, G and B flat major, await them - they certainly achieved that in 2019, by presenting, Lovell-Huckle conducting, the Mass in D, a stupendous work by Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944) - she insisted her name was pronounced 'Smith' - who also penned some ten books: in the main, collections of entertaining personal memoirs.

Their performance then coincided, aptly, with several recordings of Smyth's music, notably on Chandos (5240, 5279, 9449) and the German label CPO; although Philippe Brunelle's daring approach to her Mass on Virgin Classics (VC 7 911888-2) provided a superb interpretation which The Spires in so many respects matched. Forming something of a pattern, Dvořák's (darker) D minor Symphony was paired with Smyth's mighty and frankly Beethovenian Mass; and his scintillating D major (No 6) - pure joy - preceded that.

This time, an attractive glorious coincidence with both the Smyth (1891) and the Dvořák New World (1893), Amy Beach's Mass in E flat, begun when she was nineteen, received its first public performance in 1892.

An even more recent critical edition of

Amy Beach's Mass in E flat by Matthew Phelps,

University of Cincinnati, Ohio.

© 2014 A R Editions Inc

Beach hailed from Boston, where a bronze plaque celebrates her, and where she is also buried. Her full married name was Amy Marcy Cheney Beach (1867-1944; a further coincidence, as she and Miss Smyth died in the same year). She was a most formidable musician. She is often classed, surely with good reason (unless others remain to be rediscovered), as the first female American classical composer of note.

Amy Beach aged about nineteen,

the year she started her Mass in E

As The Spires Orchestra and Chorus demonstrated here so forcibly and impressively, her Mass is a setting of huge substance: fresh, original, powerful, imaginative, subtly varied from section to section: so that at some points she seems even to look ahead to the initiatives of the fast-approaching twentieth century. The possibility of this UK premiere derived from the expert work of Pennsylvania scholar Paula Zerkle, who completed this masterful performing edition some two decades ago, giving the work an authenticity and certainty it perhaps lacked before. (See her introduction to the edition, linked from the box below.)

Mrs Beach is not quite new to The Spires chorus: her expressive Peace on Earth featured in their autumn concert as recently as 2021. As well as a wealth of piano and chamber music and a host of solo songs, Beach's Gaelic Symphony was hailed by one critic as 'By far the finest symphony by an American composer before Charles Ives and, by a wide margin, better than a lot that came after.'

Amy Beach (centre) in Portland, Oregon

The allusion to Ives (who wrote his First Symphony in 1898-1901) is surely relevant here. The range, audacity, of her musical language displayed in the Mass in many ways even suggests the (soon to follow) proto-Modern pioneering of Ives. Indeed - the same writer hails Beach's language, not least her Piano Concerto in the galvanising, somewhat unusual key of C sharp minor: while the key does feature in some major symphonies - Mahler's Fifth, Bruckner's Ninth - as well as of course in Bach (BWV 849), Beethoven, Liszt and, famously, Rachmaninov, only Joseph Martin Kraus (1756-92), an exact contemporary of Mozart, wrote one initially in that key.

Amy Beach, probably around 1937-38, courtesy of Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH, USA

Beach's Piano Concerto has been applauded in The Gramophone and elsewhere. It is, some suggest, more convincing than works by other American composers now (justly) hailed, including the symphonist George Chadwick and Horatio Parker, whose major choral work - was it Hora Novissima, 1893? - was boldly planned for the COVID-cancelled Worcester Three Choirs Festival.

Amy Beach orchestral works, including her Piano Concerto

in C sharp minor. © Naxos American Classics

What about this magnificent, soaring performance? If The Spires' brave proclaimed ambition is (see above) 'to breathe new life into works that have lain untouched' (the Beach at least in Europe), they certainly displayed it here. The mezzo-soprano Gaynor Keeble is a formidable singer, especially experienced across a wide range of opera, and, as it happens, also starred in this choir's revealing performance of the Ethel Smyth Mass. The line-up for that - great casting - included three fabulous singers: tenor Mark Wilde, baritone Quentin Hayes and the soprano, Jeni Bern. RSAMD and RCM trained, Bern has undertaken an astonishing and fabulous array of stage roles, some of the most striking being Leonard Bernstein's Candide, Strauss's (explosive) Die Frau ohne Schatten - The Woman without a Shadow - and Arabella (plus Rosenkavalier); Kurt Weill's too rarely staged masterpiece Street Scene; the spooked child in Ravel's L'Enfant et les Sortilèges, and much more: an indication of her extraordinary range.

So for Gaynor Keeble this was a welcome return. Beach allocates the mezzo one very extended aria (we may call it), in which she was positively dazzling: treating the audience here to one of the finest performances I have heard her give anywhere. A wonderful bass solo - Peter Leadbitter - led in to full quartet in the Benedictus. In the chorus, what especially impacted was a series of spots where the composer works with just two voices, whether the upper two or conversely the tenors and basses, sometimes in a whole section of their own, sometimes building up to a flooding by the whole chorus.

One listened out for flaws in tuning; there were none. Unevenness in the choir's pacings? None at all. Indeed the only moment of doubt was in a short section for the above praised bass solo, which surprisingly hovered for a moment or two between just above the note and just below. Amid such a performance, a minor and forgivable fault.

Much of Beach's writing is, as mentioned, daringly original: frequent passages of solo woodwind, finely played, especially where allotted to Chloe Peterson's cor anglais, which of course had featured prominently in Dvořák's Largo; significant, indeed appetising, use of trumpet(s) - Martin Gardner and Laura Carvell - to herald full choir inroads; or other vocal solos that again felt as enthralling as operatic arias.

The incredible variety owed much to the conductor's evocation of shading, which showed off this masterly Mass to profoundly inspired effect. Hence the impact of a subtle, exceptionally prolonged, leisurely and intensely alluring treatment, embracing both solo quartet and chorus, of Beach's almost Baroque-quality 'Miserere'. Her Agnus Dei unfolded here with Lovell-Huckle's equally well-judged, measured slow pacing, the harp in particular audibly glowing amid the textures.

The 'Quoniam' of the Gloria emerged vividly and sprightly, helped by Beach's deft use of those tight, even minuscule motifs she deploys and exercises at times. Exploding crescendos - notably in the Credo - were offset by vastly skilled sudden diminuendos. The effect, thanks not least to meticulous rehearsal, was frequently stunning.

Amy Beach (1867-1944)

As with Ethel Smyth, this concert drew a very large audience to a musical rarity few would have heard of. Too many choral societies, whilst delivering fine performances of well-known works, lack the courage to programme in this way. Admittedly their gifted forces do wade into better-known repertoire - Bach Cantatas, Haydn, Vivaldi, Brahms, Charpentier's Messe de Minuit perhaps. But contrast those with other composers they venture into, like the Norwegian Ola Gjeilo, Coleridge-Taylor, Locatelli and Spofforth (both 1700s), Dionigi Erba, Johann Kerll, Stradella (all 1600s), Praetorius (15/1600s), Lili Boulanger, the Luciano Berio pupil Hans Richter: all a risk. These reveal a lot of bravery and pluck.

Spires Music, with their both vigorous and sensitive reading of Amy Beach's masterwork, not only provided delight to an ample audience at Coventry's (Methodist) Central Hall.

Coventry's Methodist Central Hall

They have set an example to choral societies across the country: don't be afraid of risking the unusual. By all means pair it with 'Classics we know and love'. But have the confidence that your audience has confidence in you. Don't shy away. Be bold and resolute.

Copyright © 20 May 2023

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK