ARTICLES BEING VIEWED NOW:

- Rachel Barton Pine

- Igor Stravinsky

- Cedille Records

- Delphian Records Ltd

- Arcangelo Corelli

- Xavier Benguerel i Godó

- Ravello

- Sir Colin Davis

- Sigismondo

- Dieter Schnebel

- Henry Purcell

- Jack Brymer

- Weinzweig

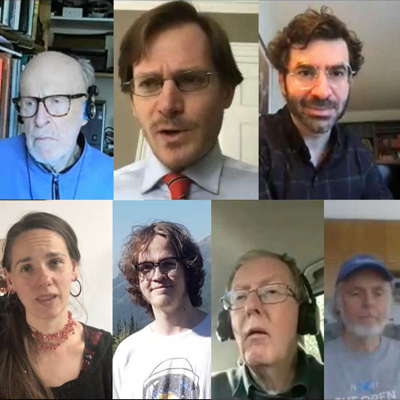

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Artificial Intelligence, including contributions from George Coulouris, Michael Stephen Brown, April Fredrick, Adrian Rumson and David Rain.

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Artificial Intelligence, including contributions from George Coulouris, Michael Stephen Brown, April Fredrick, Adrian Rumson and David Rain.

Rediscovering Scriabin

Italian pianist Mariangela Vacatello plays Scriabin from memory, heard by GIUSEPPE PENNISI

Who was Alexander Scriabin? One might ask, so rare are the performances of his works today. In Rome, on the occasion of the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of his birth, the Istituzione Universitaria dei Concerti (IUC) thought of filling the void, presenting his complete ten sonatas over two seasons. I was at the concert on 4 February 2023, where Sonatas No 2, No 5, No 6 and No 9 were performed alternating with Études (No 1, No 10 and No 11) by Claude Debussy. Mariangela Vacatello was the pianist.

Mariangela Vacatello performing at the Aula Magna della Sapienza in Rome on 4 February 2023. Photo © 2023 Giuseppe Follacchio

The concert hall was not full because of Scriabin's lack of notoriety and because riots, fomented by anarchists, were feared in the university. There were no riots, also because the anarchists are very few and far between: they belong to another era. So, it was possible to rediscover Scriabin. 'Integrals' (total works) are a feature of IUC - an intelligent way of proposing composers often rarely on the billboard.

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) as a composer - he was also an acclaimed pianist - straddles between late-Romanticism and twentieth-century experimentation. Scriabin, who was soon influenced by the works by Fryderyk Chopin, composed music characterized by a strongly tonal idiom associated with an 'early period' of his production. Later in his career, independently of Arnold Schoenberg, Scriabin developed a substantially atonal, or at least much more dissonant, musical system that drew on his personal mysticism. Scriabin associated colors with the various harmonic tones of his atonal scale. He is considered by some to be the greatest Russian symbolist composer.

Scriabin was one of the most innovative and controversial figures among early modern composers. The Soviet Encyclopedia wrote that 'no composer has been more denigrated and loved than he was'. Leo Tolstoy described Scriabin's music as 'a sincere expression of genius'. Scriabin had a greater impact on world music gradually, and influenced composers such as Sergei Prokofiev and Nikolai Roslavets. Scriabin's prominence on the Russian and then international music scene was also associated with the fact that his uncle was Molotov. In fact, however, the beginning of the twentieth century and the years immediately following the Soviet revolution were, in Russia, a period of great musical experimentation and innovation, which was put to an end with the rise of 'socialist realism' as a State poetic.

With 'socialist realism' also the fame of Scriabin, and the performance of his works, declined drastically in the Soviet Union itself. Nevertheless, his aesthetic-musical ideas were re-evaluated, and his ten piano sonatas published; supposedly, they made the most substantial contribution to the genre since the days of Beethoven's sonatas and were increasingly supported by critics and audiences.

He came from an aristocratic family. Despite his rather small hands, he became an accomplished pianist. Scriabin, who had previously been influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche's superman theories, later became interested in theosophy as well, and both of these schools influenced his music. Scriabin was for many years a member of the Theosophical Society and towards the end of his life, he came closer and closer to mysticism. He argued, in fact, that one day, heat would destroy the earth: a theory on which Vers la flamme ('towards the flame') is based, a composition in which an increasingly frightening heat destroys any sort of harmonic and tonal reference.

The theory placed colors in close relation to musical notes: he himself even played on a light keyboard with the keys suitably marked in different colors, weaving melodies outside the common sense, letting himself be carried away by this or that color and not by the note itself. Shortly before his death, he had designed a multimedia work that was to be performed in the Himalayas: 'a grandiose religious synthesis of all the arts intended to proclaim the birth of a new world' and merge all the seductions of the senses - sounds, dances, lighting and perfumes - and would have to be 'celebrated' in a hemispherical temple.

Scriabin's music gradually evolved throughout his life, which relative to other composers, was rapid and short. The evolution of Scriabin's style can be followed through his ten sonatas: the first are written in a typically late-Romantic style, while the later ones testify to the search for a new language, so much so that the last five bear no indication of tonality. Many passages of these can be called atonal.

The concert offered an interesting anthology to rediscover Scriabin. It began with the late Romantic Sonata No 2 in G sharp minor, Op 19: a very delicate andante and a presto virtuoso. This was followed by Claude Debussy's L'Isle Joyeuse, a piece full of rhythm. The first part concluded with Sonata No 5, Op 57: it is dated 1907, in full transition towards Scriabin's way of proposing the atonal scale: an allegro molto rapido, a very tense impetuoso, and a con extravaganza in which the brio blends with melancholy. After the interval, the second part opens with Sonata No 6, Op 62 of 1911, in full atonality - moderé, misterieux and concentré - followed by the sweet but philosophical Études Nos 10 and 11 by Debussy. It ended with the Sonata No 9, Black Mass of 1913: a single tempo - moderato quasi andante - a true masterpiece of dark atmosphere, which grips the listener from the first to the last moment.

Mariangela Vacatello performing at the Aula Magna della Sapienza in Rome on 4 February 2023. Photo © 2023 Giuseppe Follacchio

The pianist Mariangela Vacatello played by heart. For over twenty years, she has had an international career and teaches at the Conservatory of Perugia. She records with Brilliant Classics.

Mariangela Vacatello at the Aula Magna della Sapienza in Rome on 4 February 2023. Photo © 2023 Giuseppe Follacchio

When asked for an encore, she responded with two short excerpts by Scriabin.

Copyright © 6 February 2023

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy