- Victor Ullmann

- Claudio Ambrosini

- From the New World

- Santa Ratniece

- Alistair Hinton

- Donald Hunt

- Amy Beach

- Elizabeth Weigle

FROM ROME: From December 2009 until March 2023, the late Giuseppe Pennisi sent us regular reports from the Italian opera and classical music scene.

FROM ROME: From December 2009 until March 2023, the late Giuseppe Pennisi sent us regular reports from the Italian opera and classical music scene.

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The Creative Spark, including contributions from Ryan Ash, Sean Neukom, Adrian Rumson, Stephen Francis Vasta, David Arditti, Halida Dinova and Andrew Arceci.

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The Creative Spark, including contributions from Ryan Ash, Sean Neukom, Adrian Rumson, Stephen Francis Vasta, David Arditti, Halida Dinova and Andrew Arceci.

What's in a number?

Today's world seems ever more disposed to celebrate or commemorate anniversaries, and seemingly anniversaries that mark the passage of ever shorter periods of time. Reflecting on this phenomenon I am reminded of two things. The first is something famed record producer Joe Boyd said in relation to the 1960s and how they were different from today, or at least what was today when he made the point which is probably about twenty years ago now but the point is still valid I feel. He said that optimism produces creativity whereas pessimism produces nostalgia. I think the need to mark more and more anniversaries is an outward expression of a very pessimistic age. In an optimistic age people are looking forward not back, excited about the future about what might be coming next as in the space age. I think today's world knowing what is coming (climatic catastrophe, possible pandemics, probable wars, economic instability, ever present terrorism) finds far more comfort in looking back rather than forward.

The second thing this phenomenon makes me dwell upon is the whole arbritrary nature of why we give more importance to certain anniversaries than others. Alongside accepted religious dogma, there is little if anything apart from fickle familiarity and capricious custom as to why certain ciphers have earned so much more importance than other numbers. A day and a year are cosmic realities, but a decade, a century or a millennium are completely arbitrary. Likewise, apart from the evident difference between day and night, how we divide up a day is totally random. Other than what the bible says and the reality of the changing seasons, how we divide up a year is also merely dependent on cultural choice and nothing to do with reality. A situation exemplified by the French revolutionary calendar.

For a wonderful reflection on such and related matters, I recommend the late, and still sadly missed Stephen Jay Gould's Questioning The Millennium. As with everything he wrote, it is an enchanting exhibition of erudition, poetry and sheer human and humane effervescence. One of the points he makes in that book is that much of the importance we give to the merely arbitrary stems from our almost biological need to give some kind of order to the mass of phenomena which surround us. This for me, along with our inability to deal with mortality, is at the heart of why people collect things. All that as it may be, for today, these reflections simply serve as a perfectly arbitrary prelude and pretext to shine some light on five marvellous little-known pieces of music which just happen to be celebrating their ten times tenth anniversary in 2023.

1: Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1973):

Le Stagioni Italiche (1923)

There are longer song cycles in the repertoire than Le Stagioni Italiche but being made up of only four songs, all of which run into each other: effectively one song, which, depending on the performers, can last up to forty minutes, this piece is quite unlike anything else I know composed by Gian Francesco Malipiero, or by anyone else for that matter. The four chosen poems are a rather strange blend, maybe chosen to highlight the variety among the four seasons.

We start with a lugubrious autumnal lament on the passing of a loved one, for which Malipiero created some of his most wonderfully brooding music. Winter is represented by a text which compares the fleetingness of women's beauty to snow under the sun. Spring finds us with a poet sick of love, desperate to sing of something, anything else, even though he knows only too well that love is everywhere and in everything and that the only way not to speak of it is to remain silent. Summer is a highly charged, libidinous, indeed delirious, paean written by d'Annunzio. It starts out with pounding, thrusting chords on the piano played at an ever increasing pace and climaxes, literally, with our enflamed poet actually making love to summer itself.

At the very end we hear the opening chords of autumn once again and thus, as with Finnegans Wake (which Joyce started to write in the same year), we return full circle to complete the cycle of the seasons. The whole work is a mighty celebration of Italy's poetic and musical heritage and a forgotten jewel in Malipiero's catalogue.

Malipiero: Complete Sings for Soprano & Piano. © 2021 Brilliant Classics

2: Väinö Raitio (1891-1945):

Moonlight on Jupiter, Opus 24 (1923)

I find this title hypnotically evocative. Apparently it and the music were inspired by a dream Väinö Raitio had. The music does not disappoint in the slightest. Although the influence of Scriabin and Debussy are evident, there is enough individuality here to make this piece light years from being derivative. There is a delicacy I don't find in Scriabin and a transparency unlike Debussy. These aspects are only heightened if you look at the rather beautiful score. The writing for harp alone is quite magical. So strap yourself in and enjoy this short trip from Finland to the further reaches of our solar system.

Aarre Merikanto | Väinö Raitio. © Fennica Nova

3: Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942):

Five Pieces (1923)

This set of short dances for string quartet demonstrates as well as anything the pure musical genius of Erwin Schulhoff. The wealth of melodic, harmonic, rhythmic and stylistic invention displayed within such a short span is quite breathtaking. There are influences, notably from Stravinsky, Bartók and folk music, but from these ingredients he brews up something unique and absolutely original. These pieces must be a joy to perform too.

Ervín Schulhoff: Czech Degenerate Music Vol 4 - Chamber Music.

© 2004 Praga Digitals

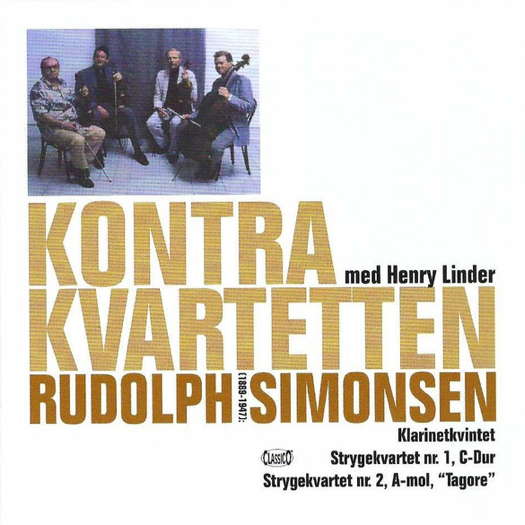

4: Rudolph Simonsen (1889-1947):

String Quartet No 1 (1923)

Rudolph Simonsen's only claim to fame is the fact that his second symphony won a bronze medal for Denmark at the 1928 Olympics. (No gold or silver was awarded that year.) In today's sport obsessed world it seems very hard to imagine awarding medals for artistic achievement alongside athletic prowess at the Olympics. It seems like something from a bygone age, but if that were to make you think that Simonsen's music deserves to be left to gather dust on a shelf beside his bronze medal, that would be a mistake. His output was small but, especially in the case of his chamber music, of high quality. Choosing to write his first string qaurtet in the key of C major may only add to the idea that his music was anachronistic. None of that matters to me: I simply chose to put this work here because I find it a powerful piece of convincing compositional artistry.

Kontra Kvartetten - Rudolph Simonsen. © 2005 Classico

5: Alfredo Casella (1883-1947):

Concerto, Opus 40 (1923)

The first piece I chose today was cyclical, so I have decided to follow suit and end where I began, in Italy. I also started by asking what's in a number?; I could finish be asking what's in a name?, as this Concerto by Alfredo Casella is in reality a straightforward string quartet.

As with the Malipiero above, Casella may have chosen his title in order to connect this piece with the pre-operatic tradition of Italian music and/or likewise in an attempt to renew the idea of what a string quartet could be, especially for an Italian composer at this time. There was a time, more or less a decade ago when Casella was flavour of the month among record companies, with Chandos and Naxos simultaneously releasing most of his orchestral repertoire. This world premiere recording of this very important work in Casella's catalogue is one of the definite highlights of that purple patch.

Alfredo Casella - Guido Turchi - Quartetto di Venezia. © 2013 Naxos Records

So that's your lot for this week: five composers, four countries, three string quartets, and two questions. I am sorry to say, however, that I don't have a partridge in a pear tree to offer – maybe next week.

Copyright © 12 February 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain