- Gustav Mahler

- Egyptian

- Howard Beach

- Siberia

- St John's Smith Square

- Simon Farrugia

- Meyrick Alexander

- Khukhoo Namjil

SPONSORED: An Integral Part - Lindsey Wallis looks forward to the Canadian Music Centre's tribute concert to composer Roberta Stephen.

SPONSORED: An Integral Part - Lindsey Wallis looks forward to the Canadian Music Centre's tribute concert to composer Roberta Stephen.

All sponsored features >>

SPONSORED: A Seasoned Champion of New Music. Argentinian-American pianist Mirian Conti in conversation with Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: A Seasoned Champion of New Music. Argentinian-American pianist Mirian Conti in conversation with Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

The Roots of Magic

One of the very greatest pop songs of the 1960s asked Do You Believe In Magic? To which my answer is, and always has been a resounding yes I do. After what I said about astrology in my last piece in this series, that statement may well surprise. For that reason, before I go any further, allow me to qualify that affirmation somewhat. Magic of the miraculous variety, water into wine shenanigans, along with any kind of hocus pocus, open sesame, mumbo jumbo or voodoo I regard as what it is; a perfectly understandable and logical - but totally erroneous - creation of our minds and imaginations in the distant past that can be explained as a natural, indeed inevitable reaction on the part of our overwhelming ignorance about and fear of our surroundings and the seemingly malevolent or at least capricious forces that controlled them but whose veracity today lies solely within the pages of children's stories or the best fiction.

A 1902 photo of a Yukaghir shaman

Or as William Hazlitt put it more succinctly:

The origin of all false science and imposture is in the desire to accept false causes rather than none, or which is the same thing, the unwillingness to accept our own ignorance.

A Chaos magic ritual involving videoconferencing

However I do believe - in fact I don't think belief is the right word as I feel this is just fact evidenced by experience - in the mysterious, inexplicable (or at least as yet unexplained) capacity of certain phenomena to have a wholly transformative power over us. This is what I consider magic. Love is an example of this kind of phenomenon, which I suppose is a sort of sneaky sloppy spell cast by natural selection upon us in order to ensure we continue to pass on our genes. But the evolutionary explanation and biological reality of love is light years away from how it is actually experienced by human beings. Likewise with music.

Egyptian lute players in circa 1350 BC

Indeed for me music and magic are basically synonymous. Think about it. What actually is music? A series of senseless rapid frequency waves in the air caused when an object is struck or air passes across a membrane of some sort that reaches our eardrums causing them to vibrate in a way that sets off a chain reaction that ultimately leads to the auditory nerve sending an electric signal to our brain which we perceive as sound. That's it. That's all music is. That said however, the gulf between this reality, wonderful as it is - made even more so by the fact that a lot of the intricate machinery in our ear which makes the phenomenon of music possible is just a random evolutionary development of what used to be a jawbone - and how music is actually and viscerally experienced by us is wherein the magic lies. The effect these wavelengths can have on our minds, hearts, souls and bodies is out of all proportion to their rather mundane physical reality. It is akin to the philosopher's stone that alchemists sought in vain for centuries in its ability to transmute base metals (sound) into gold (music). All the music that means the most to me is imbued with a tremendous sense of mystery and strangeness. An ability to create sounds, moods and sensations so utterly different from the everyday, the merely human, an ability to literally create other worlds and new realities. One of the very greatest exponents or practitioners of this otherworldly kind of magic is the subject of this piece: Maurice Ohana.

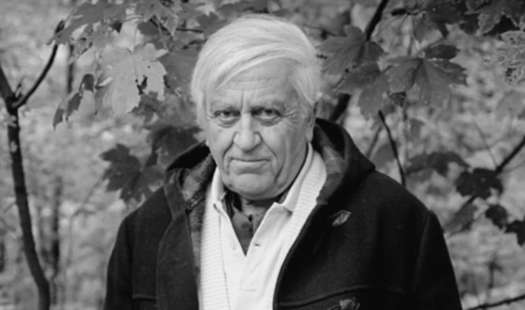

Maurice Ohana (1913-1992). Photo © Dominique Souse (dominiquesouse.com)

Mr Ohana, what nationality are you? Well I was born in Morocco while it was under French occupation in 1913, although all my life I led people to believe it was 1914 because I was superstitious about the number thirteen. My father was an Andalusian Sephardic Jew but having been born in Gibraltar was officially a British subject as was I until I became a French citizen in 1976 and my mother was Spanish, so you tell me.

This imaginary conversation is just one of the many aspects of Ohana that I like so much. Another, I digress, is that while so many of his posing peers did a lot of political posturing during and leading up to the Second World War, Ohana meanwhile left the café and volunteered for and saw active fighting in a British Army uniform against the Nazis. In a world so desperate to put labels on people especially of the nationalistic variety, where - to paraphrase Joseph Roth, everybody wants to know where you come from and nobody cares to know where you are going - Ohana's plural identity from birth is a wonderful antidote to and example of just how wrong-headed, short-sighted and historically ignorant this pigeonholing mentality can be. At best I think we can say that Ohana was Mediterranean or simply European in the sense that despite the apparent differences of language, ethnicty and religion, all the peoples who live and have lived in this region of the world have as much in common with each other as anything that distiguishes them.

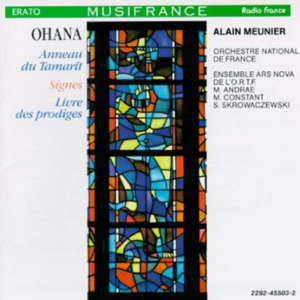

In the late spring and early summer of 1965 - by a blithe stroke of serendipity the very same summer that John Sebastian asked us that question above - Maurice Ohana composed a piece called Signes which bears the subtitle The Tree; a piece which encapsulates as well as anything he ever wrote his shaman-like powers of magic. Like many of his pieces the title begins with the letter S, a letter which had important and powerful symbolic resonance for Ohana. It is a work for chamber ensemble mostly of percussion that includes three important roles for flute, piano and most magically of all a zither tuned in third tones as opposed to the more typical semitone tuning. The three soloists in the first performance were also the three dedicatees of the piece. It is played without a break although it is divided into six sections each of which has a title relating to the tree in different situations and predicaments.

We start with The Tree at Night which is for the full ensemble and lets us know from the opening bars that we are in an utterly unique and utterly magical nocturnal soundworld. A Hymn to the Night indeed. The sound of the zither seems to want to recreate the atmosphere of a lost Mediterranean past. A pre-Christian indeed pre-Roman past, maybe even a pre-human one.

Listen — Maurice Ohana: The Tree at Night (Signes)

(excerpt) Monique Rollin, zither; Ensemble Ars Nova de l'ORTF. ℗ Warner Classics :

This world is also hinted at in his wonderful trio from a decade later titled Sacral D'Ilx. Ohana always maintained that the natural world taught him more about music than anything or anyone of the human variety. Maybe this is what I find so powerful and mesmerising in this music, its totally non-human texture and quality. As extraordinary as the colours and moods of these openings pages are, it is also no surprise to learn - as you can sense a very definite structure underlying all the kaleidoscopic effects - that Ohana studied architecture before he studied music.

The next section is titled The Tree Enlivened with Birds. It is the longest section and one where the flute is the main protagonist. Clearly with all these arabesques there is some attempt at the representation of birdsong here but it is some way from anything like Messiaen's more literal or authentic attempts to do the same. This is Ohana's world, not ours. The untuned percussion leads us into the third section: The Tree Drenched by the Rain. A section where the full battery of tuned and untuned percussion weave their magic and are given their chance, well clearly not to shine but at least to sing in the rain. Then comes The Tree Imprisoned by Gossamer which is zither time. The title alone is hypnotic enough; the music only augments this state. After which we have a wild toccata which, apart from some touches of percussion, is for piano solo - Ohana's own instrument - which is titled The Tree Battered by the Wind.

Listen — Maurice Ohana: The Tree Battered by the Wind (Signes)

(excerpt) Christian Ivaldi, piano. ℗ Warner Classics :

I am not sure if the tree is more battered or bewitched as I have never heard the wind dance with such abandon. Here maybe Ohana is paying his debt to Debussy.

The closing section, The Tree Burnt by the Sun, sees the full ensemble back to bask in the midday heathaze. The percussion here creates a wonderful sense of stasis - a sun-sapped langour, before an almightly blast on the gong leads into the closing bars where the lone flute has the last say, like a little bird scurrying away for protection into the lattice of the tree's foliage rich shelter.

Listen — Maurice Ohana: The Tree Burnt by the Sun (Signes)

(ending) Michel Debost, flute; Ensemble Ars Nova de l'ORTF. ℗ Warner Classics :

In all of these articles I have written, here I have never felt words to be quite so inadequate to give even the merest sense of just what an experience this music is like to listen to. Therein lies the magic.

Copyright © 16 December 2022

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain

ECHOES OF OBLIVION - FURTHER INFORMATION

TWENTIETH CENTURY CLASSICAL MUSIC