- Orphée et Eurydice

- Alan Vaness Chakmakjian

- harpsichordist

- Johan Helmich Roman

- Michele Enrico Carafa di Colobrano

- Teizo Matsumura

- music festivals

- Maya Angelou: A Brave and Startling Truth

Nothing Written in the Stars

Few people, whom I don't know personally, have ever made me laugh as much or as hard as that great Scot Billy Connolly. His quip about 'What star sign are you?', to which his answer was 'Pyrex', just about sums up my attitude to the whole murky world of astrology and horoscopes. Furthermore I am not one of those people who view these phenomena as 'merely a bit of harmless fun'.

Some critics of astrology, from left to right: Cicero, Isidore of Seville, Martin Luther and Billy Connolly. (Billy Connolly photo by Eva Rinaldi, CC BY-SA 2.0, creativecommons.org)

I have never come to terms with the hypocrisy of our society whereby in lecturing our children on the importance of study, in order to prove the point we send them to school for a dozen years or more so that they can learn what is true and what is false, get their bearings in the thornier landscape of what is right and what is wrong and be given the materials, tools and skills that enable them to defend themselves as thinking individuals in the adult world. Yet when we encounter adults who have their brains full of bubblegum and their imaginations inebriated with ideas that frankly amount to a steaming heap of intellectual excrement, we are supposed, indeed expected, to respect such gibberish, thereby showing just how mendacious and disrespectful we can be towards our own children. We do ourselves and society in general no favours by behaving in this hypocritical fashion. I respect most people far too much to have even the slightest respect for a lot of the drivel that drools out of them.

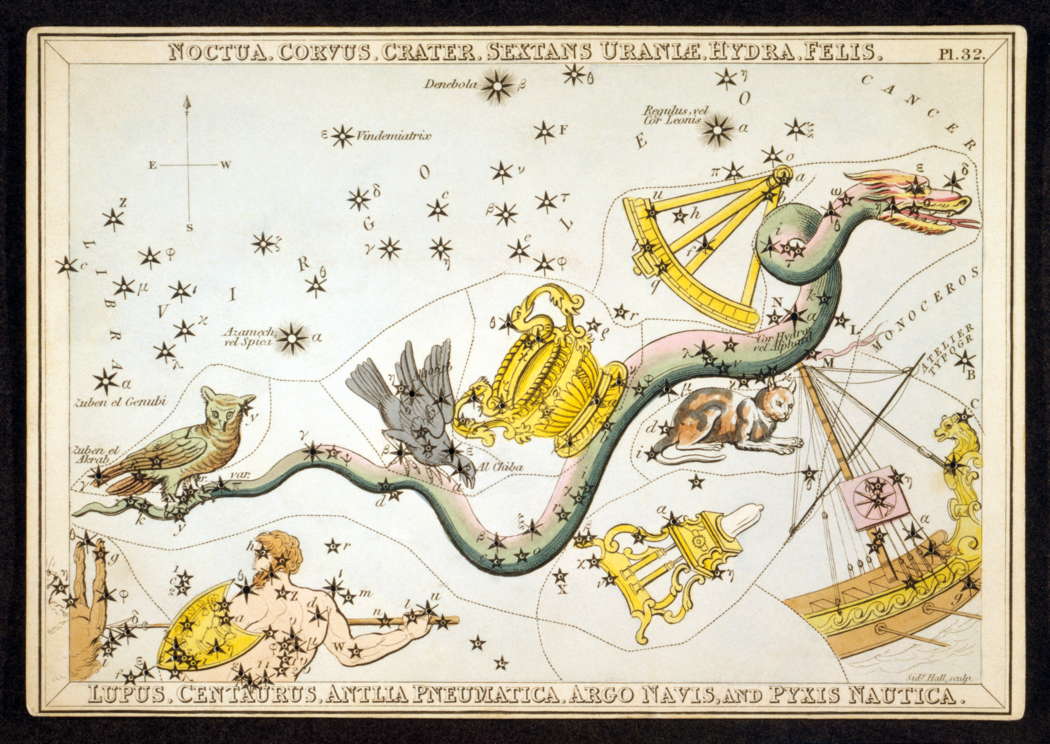

Noctua, Corvus, Crater, Sextans Uraniæ, Hydra, Felis, Lupus, Centaurus, Antlia Pneumatica, Argo Navis and Pyxis Nautica (1825, as depicted in Urania's Mirror) by Reverend Richard Rouse Bloxam (1765-1840), engraved by Sidney Hall (1788-1831)

The late great Carl Sagan, in his excellent The Demon-Haunted World, gives the example of a curious, intelligent well-read taxi driver he met who was totally fascinated by extra-terrestrials, speaking with the dead, crystals, Nostradamus, the shroud of Turin, Atlantis: all manner of hogwash and yet the same curious cabby knew literally next to nothing about science: real science, of how we, the rest of life, planet earth and the universe are made, came to be so or function in reality. Depressing as this state of affairs is, if one reflects, one can see how, despite the best efforts of a public or private education, many people remain, whilst seeking a heart in a heartless world, immune to truth when faced with the array of facile, falsely optimistic answers provided by popular culture and those who wish to maintain power by keeping the masses in thrall to 'their' version of what's real, what's true, what's normal.

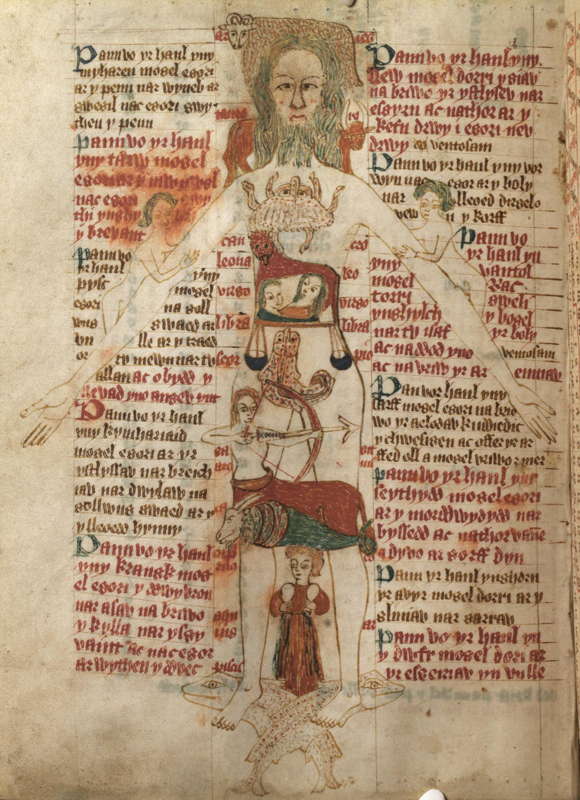

The Zodiac Man by Welsh language poet Gutun Owain (flourished 1456-97)

I could say that it is equally or even more depressing that so many creative geniuses have likewise believed in, accepted the truth of or at least been sufficiently intrigued by utterly fatuous notions. Yet if this had not been the case we would now be much the poorer for it, as astrology and the like have inspired many extraordinary works over the centuries, even in modern times. When we consider that the whole artistic project, creativity in general, has a deeply irrational component, I suppose one should not be too surprised that similarly irrational, mysterious ideas have had and continue to have such a fascination for creative souls. Such is the case with the attractions of astrology to Robert Gerhard. Before I go any further, I will be using the name Robert here rather than Roberto as he was born Catalan and Robert is the Catalan version of his name.

Album cover for Roberto Gerhard: Chamber Music 1 (Métier MSVCD 92012). © 1996 Divine Art Ltd / Diversions LLC. Catalan-born composer Robert Gerhard i Ottenwaelder (1896-1970) later settled in Cambridge, UK

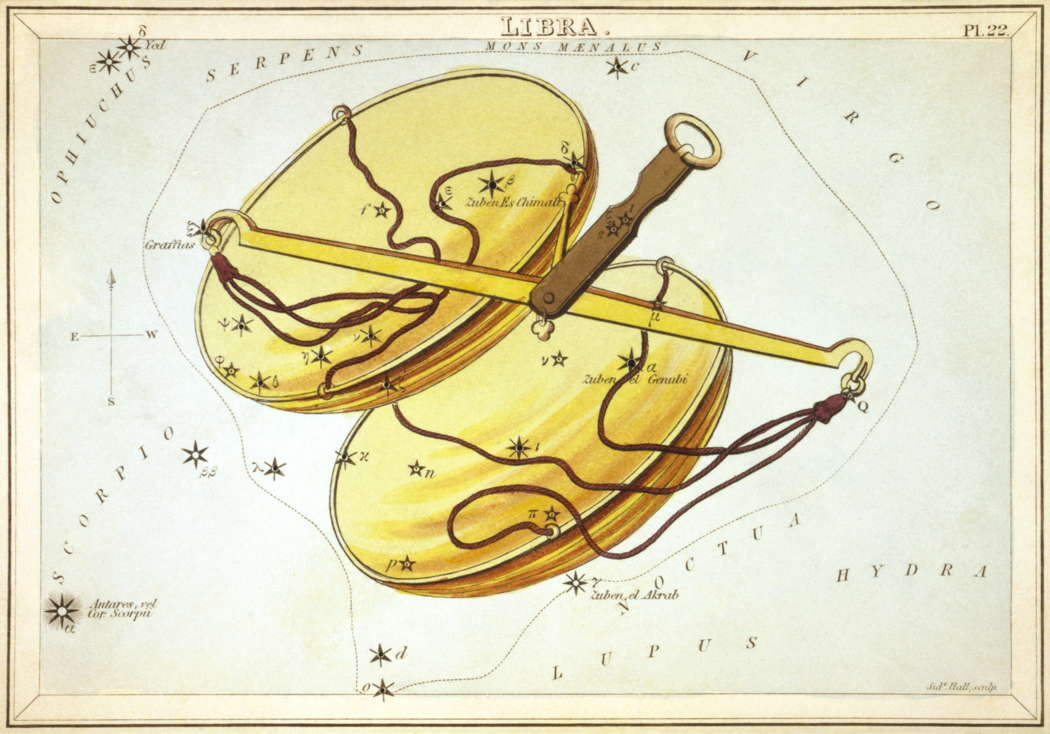

For the astrologists and their faithful followers out there, I not only share a name with this great composer but also a star sign: we are both Librans; indeed as it happens we were both born on exactly the same day of the year. What do all these coincidences mean? Absolutely nothing except pure, random coincidence.

The star sign Libra (1825, as depicted in Urania's Mirror) by Reverend Richard Rouse Bloxam (1765-1840), engraved by Sidney Hall (1788-1831)

My love of and enormous esteem for the music of Robert Gerhard, however, owes absolutely nothing to coincidence nor to the stars, but solely to the sheer creative genius of the man, his mind and his magic.

Gerhard was as averse as any composer to the idea that music could be explained, indeed he thought the whole notion was a fallacy. He always maintained that, as regards music, the sense was in the sound, whereby he meant that if his music didn't mean something, in whatever fashion, to a listener as a purely audible phenomenon and experience, then all the detailed analysis in the world of the work in question would amount to nothing and have no bearing on a listener's opinion of a piece.

With that proviso I will not dare to analyse as such any of Gerhard's works but merely try to describe to a small extent and give my opinion about the works he wrote that are informed or inspired by astrology. The first of these that I wish to comment on is the one that is named after his own star sign: Libra. It is a piece written in 1968, by which time he was a British citizen, for a wonderfully rich-hued ensemble of flute (doubling piccolo), clarinet, violin, guitar, piano and percussion that is divided into nine, more or less, clearly discernible sections that are played without a break. In a piece that lasts no more than a quarter of an hour, the variety of textures and smörgåsbord of sonorities that Gerhard serves up for us to savour is quite breathtaking. Every instrumentalist is given their chance to shine in the same way I have always felt that all his orchestral works are basically concerti for orchestra. The percussion is like an ensemble all on its own.

The haunting heart of this piece is first hinted at by the flute not long after the opening, but it is postponed until the closing minutes. Before then we pass through a kaleidoscopic hall of mirrors of varying combinations of instruments, moods and tempi. Then towards the close the piano sets up a low rumbling ostinato as the clarinet plays the simplest of folk-like melodies accompanied by glissandi on the timpani and what I believe is the high E string of the guitar whilst the piccolo soars and the percussionist caresses a cymbal until the whole ensemble slips into nothingness. The overall effect is simply magical. If this piece is indeed a portrait of the composer in however a conscious or unconscious way and the sense is in the sound, then there are few compositions if any that I have heard that make as much sense as Gerhard's Libra.

Listen — Robert Gerhard: Libra (ending)

℗ Nieuw Ensemble / Ed Spanjaard :

The next piece that Gerhard composed, and sadly the last he was to complete before his death in 1970, was Leo, which was the star sign and name of his wife of forty years whom he had met whilst studying with Schoenberg in Vienna in 1925: Leopoldina Feichtegger. The fact that the Schoenbergs' second daughter was born in Barcelona and bears the name Nuria is testimony to the esteem in which Schoenberg held his young Catalan pupil. Leo is a bigger piece than Libra in every sense. It lasts longer and calls for more musicians. Along with the forces needed to play Libra there is in addition a horn, a trumpet, a trombone and a cello. The pianist also plays celeste and a second percussionist is required.

Leo is arguably the most succinctly sumptuous example of the incredible freedom Gerhard had attained in his hard-won unique style at this stage in his life. In that sense it reminds me of listening to late Elliott Carter. The closing minutes of the work, when you hear it for the first time, or more accurately, when you hear it for the first time after having heard Libra, are literally jaw-dropping. The same music that ends Libra returns at the end of Leo. It's not identical - the cello replaces the guitar - but it's utterly unmistakable.

Listen — Robert Gerhard: Leo (ending)

℗ Sinfonietta ESMRS / Pascal Rophé :

To use the same music to end a musical portrait of himself and a separate piece of music that was a portrait of his wife I find one of the most beautiful and moving things I have ever come across in all my listening. What exactly that clarinet melody is has never been definitively identified, which for me just adds to the romance of the piece, as I like to think it was a secret melody known only to this couple. The fact that these two pieces are the greatest celebration of marriage in music that I can think of is only heightened by the third piece of Gerhard's that bears an astrological title: Gemini. In 1966 he had written a piece for violin and piano which he called simply Duo Concertante. It was not until after he had completed Leo that he renamed this work, for two opposite but complementary personalities, Gemini. What star sign, indeed what title, could be more befitting for the union of two hearts and two souls forever betwined?

Listen — Robert Gerhard: Gemini (extract)

℗ 2022 Miranda Cuckson, violin; Eric Huebner, piano (ps21chatham.org):

'Gemini' design for a 2003 Russian two-Rouble coin

Being as we are in the centenary of the publication of Joyce's Ulysses, there is an anecdote and a completely personal whim that I would like to add to finish this piece. Gerhard, for as long as he knew his wife, always called her 'Poldi' and conversely, in Joyce's Ulysses, Molly Bloom always refers to her husband Leopold as Poldy. In a tale, as this article has been, of the union of man and woman, where two become one or one becomes the other, where man becomes woman and woman becomes man, I find this purely coincidental parallel in the separate lives of a musical and literary genius, of fiction and reality, quite charming. It is even exacerbated in that Leopold Bloom is often viewed, indeed mocked, as a 'womanly man': the ultimate Gemini-like union of opposites.

Copyright © 19 November 2022

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain

ROBERT McCARNEY'S ECHOES OF OBLIVION

CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT CATALUNYA

TWENTIETH CENTURY CLASSICAL MUSIC