- Götz Friedrich

- Lyrita Recorded Edition

- John Bingham

- surtitles

- Lukas Foss

- Norwegian National Opera and Ballet

- Luis Buñuel

- Eric Whitacre: Leonardo Dreams of his Flying Machine

VIOLINIST, TEACHER & STORYTELLER

ANETT FODOR presents two amusing anecdotes which Carl Flesch shared with the readers of Hungarian newspapers

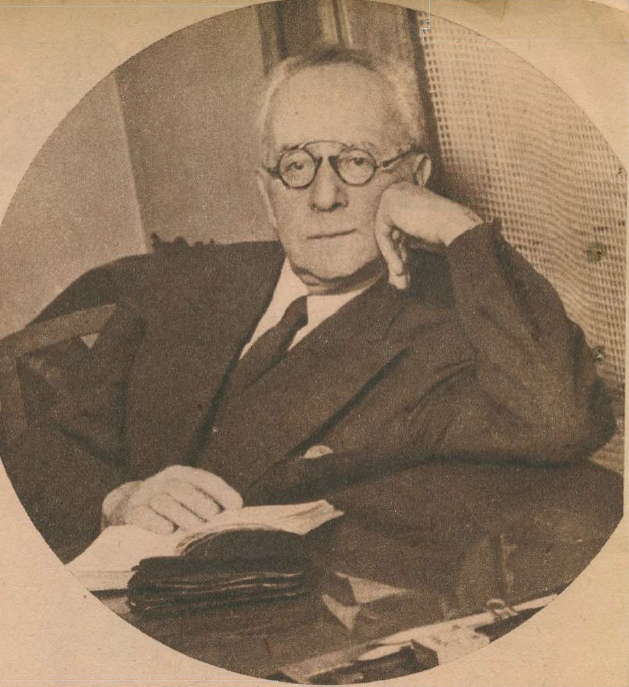

The world-famous violinist and well-renowned teacher Károly/Carl Flesch was born in Moson (today Mosonmagyaróvár), Hungary, on 9 October 1873. At the end of the nineteenth century, he was the student of Jakob Grün in Vienna. Later he was taught by Martin Marsick and Eugene Sauzay at the Paris Conservatory.

Károly/Carl Flesch was born in this house in Mosonmagyaróvár, Hungary.

Photo © Anett Fodor

After completing his studies, Flesch taught at the Conservatory in Bucharest and was the leader of the Romanian Queen's string quartet. For five years he taught at the Amsterdam Conservatory and also held a celebrated series of concerts in Germany. He achieved international recognition as a member of the Schnabel-Flesch-Becker Trio and became a distinguished professor at the Music Academy in Berlin. He also taught at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia.

Carl Flesch (Source: Szinházi Magazin, 13 January 1943)

His students included such world-renowned soloists as Henryk Szeryng and Ida Haendel. Flesch wrote several books including: Urstudien (Ancient Studies), Die Kunst des Violin-Spiels (The Art of Violin-playing), Das Skalensystem (The Scale System), and Das Klangproblem im Geigenspiel (The Problem of Resonance in Violin-playing).

However, apart from his musical publications, he also shared some amusing anecdotes of his twelve stays in America with the readers of Hungarian newspapers. Here I would like to present two of them.

ONE

Thomas Alva Edison was the most famous person I have ever met. In 1923, the director of the Edison Society let me know that Edison wanted to meet me in person. So, one afternoon, I went with my piano accompanist and my violin to Orange near New York where the mysterious inventor lived in his studio.

Edison was a short, stout, snow-white haired old gentleman with wonderfully blue, childish eyes. Our conversation did not flow freely because Edison was completely deaf. He wore a hearing aid on his belly, which he had invented just for himself, but it was his only invention that was absolutely useless. If you wanted to make yourself understood, you had to shout loudly in his ear. Interestingly though, he could hear music well and was more sensitive to musical vibrations than a person with normal hearing.

Unfortunately, however, I must say that Edison's taste in music was extremely poor. He asked me to play many little pieces for him so that he could choose which he could make into a recording. His critiques were always clear and concise. He would either say, 'good seller' (that'll sell) or 'bad seller' (that won't). Sometimes it was the least successful pieces that gained his favour. I stayed with Edison for two and a half hours. A few days later he sent me his photo with a flattering dedication.

I also learned that Edison's best friend was America's other very famous man, the car manufacturer, Henry Ford. Ford always had a passion for the violin. He owned a remarkable collection of precious Italian master violins.

[Source: Szinházi Magazin, 13 January 1943]

TWO

When I gave a concert in the United States this year (1926), my destination was Iowa City. This small town of 20,000 inhabitants has a University attended by at least eight thousand students. It is therefore called a 'University Town'. At such an American university, every imaginable subject the human mind can conceive is taught, eg Medicine, Law, Journalism, even Music and the Fine Arts.

On the morning of the recital, after a thirty-six-hour journey, I arrived at my destination. Two young men were waiting for me at my hotel, introducing themselves as being from the Daily Iowan. They were extremely curious about all sorts of things which were nobody's business. After satisfying their thirst for knowledge as best I could, I went down to the restaurant to fortify myself with all the delicious varieties of dishes that are served at an American breakfast.

But I could not enjoy this pleasant occupation for very long, as two ladies from the Iowan Telegraph appeared, wishing to speak to me urgently. I feared that if I kept them waiting, my popularity in Iowa City would be seriously damaged, so I asked the ladies to come in. The ladies - one blonde, the other brunette - asked me what violin I played, when Stradivarius was born, when he died, if he was married, etc. After I had been helped out of the situation with a few inaccurate replies, I unpacked my tailcoat - and tried to smooth out the careless wrinkles that the garment had acquired on the long journey.

While I was doing this, two correspondents from the Iowan Express appeared and asked me to tell them some intimate details of my family life and whether I was a fan of jazz music. This great and sustained attention of the Iowa press in my regard caused me a certain unease, arising as it did from my sense of artistic responsibility and need to strengthen my self-confidence, which can only be overcome by direct contact with my instrument. Therefore, I decided to have a short rehearsal with my piano accompanist. At the same time, I could not help but acknowledge, with a fitting admiration for the importance of American journalism, the rather large number of newspapers that such a relatively small town as Iowa possessed.

As I was about to leave the hotel with my violin tucked underneath my arm, two ladies stood in my way and, after ascertaining my identity, asked me cordially but forcefully not to deprive the readers of the Iowan Dispatch of my point of view on the difference between American and European concert life.

'This is the fourth interview in an hour', I remarked with self-confidence, 'there can hardly be any more newspapers in Iowa!'

'What do you think', said the reporter, 'there's only one newspaper here.'

'But what the hell', I exclaimed, 'what sort of people have been asking me about all kinds of possible and impossible things since I arrived?'

'Well', said the little one with unshakeable self-confidence, 'we are all students at the Journalism Seminar, and when anybody famous comes to Iowa City, the whole class interviews them in order to practise.

'And how many students are in the Journalism Department', I asked with feigned calm.

'Two hundred and thirty-five', came the reply.

It became clear to me that only a quick escape from the young generation of journalists could save me. I inquired about the address of the nearest steam baths and left its protective haze only just before the concert began.

[Source: Brassói Lapok, 16 May 1926]

Unfortunately, this was not Flesch's only escape – he lived through a more perilous one. Because of his Jewish origins, Flesch had to leave Germany and go to London in the 1930s and was arrested by the Gestapo in the Netherlands after the German invasion. Later, thanks to Furtwängler's active intervention, he was finally released.

Ernő Dohnányi and Géza Kresz successfully managed to re-obtain Flesch's Hungarian citizenship, so that after his dreadful ordeal in the Netherlands, he was again able to return to Hungary, interestingly enough via Germany.

In December 1942, the weary, almost seventy-year-old Flesch gave a concert in Budapest, performing Beethoven and Brahms violin concertos. With the further assistance of Dohnányi, he was offered a position at the newly founded conservatory in Lucerne, but was only able to enjoy his re-established peace of mind for just over a year. He died in Switzerland on 15 November 1944.

Plaque on the wall of the birthplace in Mosonmagyaróvár, Hungary of violinist and teacher Károly/Carl Flesch. Photo © Anett Fodor

Due to the Second World War, news of his death arrived in Hungary rather late. Fifty years later, in 1994, the Community Centre of Mosonmagyaróvár was named after Károly Flesch. The ceremony was attended by Károly Flesch's son and Ida Haendel, his former student who played the Brahms Violin Concerto, which was a huge success. On the same day, the ashes of Károly Flesch and his wife were re-buried in the family tomb at the Jewish cemetery of his hometown.

Copyright © 24 October 2022

Anett Fodor,

Győr-Moson-Sopron, Hungary