ARTICLES BEING VIEWED NOW:

- Régine Crespin

- Hector Berlioz

- Ruth Railton

- Marina Koshetz

- Marián Varga

Time to Become More Widely Known

KEITH BRAMICH listens to orchestral and chamber music by Adrian Williams

Human history is complex. Changes are often not gradual but sudden, in response to game-changing world events.

As children, distant human past can often seem irrelevant, but as we travel through our lives and experience some of these happenings for ourselves, our perspective begins to change. As an example, my first direct involvement with history was the fall of the Berlin Wall and its various knock-on effects, changing the shape of Europe.

Since then, a whole series of dramas, such as the Yugoslav Wars, 9/11 and other acts of terrorism, the Iraq War, the Arab Spring leading to civil war in Libya, Fukushima, the ongoing conflict in Palestine, Crimea, #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, Brexit and, most recently, the Coronavirus pandemic, have all left their mark on an increasingly globalised society.

Even more complicated is each generation's re-writing of history. Sometimes this can mean sudden modifications and omissions, from a new perspective. Colonel Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein, Jimmy Savile's BBC, Harvey Weinstein, the pre-Joe Biden US Presidency and the toppling of slave trader statues all come to mind, as do various hopefuls from the current government of part of a small archipelago near France. Will these colourful characters be forgotten forever, or will some of them be re-invented by later generations along the lines of Billy the Kid, Butch Cassidy, Jesse James or Dick Turpin?

As we travel back in history, so each period's heroes and anti-heroes have been re-invented and re-imagined more and more times. Take Robin Hood, for example. Was he a force for good or evil? The answer clearly depends on one's political leanings, personal wealth and colour preferences, as well as which version(s) of the legend one has experienced. There clearly was no Errol Flynn nor music by Erich Wolfgang Korngold in the fourteenth century.

Then there's the case of one Edward Kelly. Born in Victoria, Australia in December 1854 to Irish parents, life's forces were stacked up against the young lad right from birth. His father, transported from Ireland, died shortly after serving his prison sentence. This left Ned, the third of eight children and the eldest male, as the family's breadwinner, and so began a colourful life of murderous crime as outlaw, gang leader and bushranger which ended, aged twenty-five, when he was captured and hanged following a shootout with the police. Kelly, notoriously wearing a bullet-proof suit at the time, was his gang's only survivor of the gun battle, and with his reported final words on the scaffold of 'such is life', he was catapulted, in Pythonesque fashion, straight into Australian legend.

Ned Kelly, aged fifteen

As with Robin Hood, Ned Kelly's hero/anti-hero status is unclear and vehemently argued by Australians, past and present. It seems that this ambiguity is a requirement for legendhood. Kelly, an icon of the Irish Catholic, working-class struggle against British colonial establishment, is now an international cult figure, and his story has been told countless times in various media. His many on-screen appearances, none involving Flynn or Korngold, to my knowledge, began with the world's first dramatic feature length film, The Story of the Kelly Gang, a silent movie from 1906. Various incidents from the Kelly legend also inspired a now famous series of 1940s Australian paintings by Victoria-born Sidney Nolan (1917-1992).

Australian artist Sidney Nolan in the 1940s. Photo: Albert Tucker

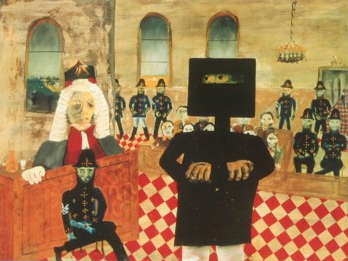

The works are, in fact, the best-known of Nolan's diverse output, and his angular depictions of Kelly in armour have themselves become an Australian icon. Although they depict various episodes from Ned Kelly's short life, Nolan produced stylised and generalised images of betrayal, injustice and love. See what I mean about the re-inventing of history and legends?

Sidney Nolan's painting of the trial of Ned Kelly

Sydney Nolan moved to England, initially London, in 1951, and in 1983 he moved to Herefordshire, making his home and studio at The Rodd, north of Kington, near the Welsh border. In 1985 the Sidney Nolan Trust was founded. It was designed to support artists and musicians, and to provide exhibition space for work by Nolan and others. Nolan met the young English composer Adrian Williams (born 1956), one of the founders of the Presteigne Festival, who was living in the area, and who used to practise on Nolan's piano.

Adrian Williams at home in the Welsh Borders, close to Hergest Ridge.

Photo © 2018 Keith Bramich

In 1998, Williams, fascinated by Nolan's work, wrote the chamber concerto Portraits of Ned Kelly, based on Nolan's paintings, and this concerto received a rare performance recently, streamed last night (11 June 2021) via the English Symphony Orchestra (ESO) website. The performance was recorded on 8 April 2021 at Wyastone Hall, Monmouth, Herefordshire UK by members of the English Symphony Orchestra, guest leader Emily Davis, conducted by Kenneth Woods.

Before attempting to describe the music and the performance, I should, for reasons of transparency, tell you that I've known Adrian Williams personally since 1989, and that I'm writing this without access to scores. Williams describes the work as a kind of modern-day Till Eulenspiegel - another legendary hero/anti-hero, notice - and conductor Ken Woods adds the words 'on acid', also calling it 'brilliant and exceptionally virtuosic'. The work is scored for eleven instruments - single strings with woodwind quintet (plus usual doublings) and harp. Judging by the high standard of performance, I suspect that quite a bit of rehearsal time went into making this recording.

Members of the English Symphony Orchestra and Kenneth Woods performing Adrian Williams' chamber concerto Portraits of Ned Kelly at Wyastone Concert Hall

The video stream of the performance contains views of many of Nolan's Ned Kelly paintings - albeit only in very low resolution - and the music, running for just over twenty minutes in what sounds like one continuous movement, is extraordinary for its variety of moods and depiction of the various fantastic-sounding scenes in an almost second-Viennese-school style which sounds, to me, extraordinarily different from any of Williams' other works, or at least those that I know. It's as if Williams has been gripped and transformed by the contents of these Australian scenes. (Another re-invention of the legend?)

Williams is the ESO's current John McCabe Composer-in-Association, and has drawn the short straw, unfortunately, by holding this position during the current pandemic period, although Ken Woods has also programmed other works by and arranged by Williams recently. The title of last night's concert was A Composer Portrait: Adrian Williams, and it's a huge pity that this couldn't have been a live concert with a local audience. There were two other works on the programme, recorded on a different occasion - 21 September 2020 - with an exactly twice larger incarnation of the English Symphony Orchestra, this time strings only, still conducted by Ken Woods, but this time led by Zoë Beyers. It was great to see friends Alice McVeigh and Anna Joubert at the back of the cello section!

The nearly ten-minute Russells' Elegy for string orchestra is a 2011 adaptation of the slow movement of Williams' String Quartet No 4 (2009). The title refers to the passing of two men who have been important in Adrian Williams' career. Williams worked briefly with film director Ken Russell (1927-2011) in the 1990s and they discovered a shared love for wild places and late Romantic British music. Conductor, pianist and close friend of Finzi, John Russell (1916-1990) was one of Williams' teachers at the Royal College of Music. (Read more about Williams' association with John Russell here.) The music, with its important viola solo, and in a much more traditional style, is mostly quiet, reflective, poised and pastoral-sounding, but with a climactic outpouring of grief towards the end.

Lastly, in this superb fifty-minute online concert, Migrations for twenty-two solo string instruments, very different again, is a fragile and almost minimalist-sounding meditation on the migration of birds - not humans (although at one point in the music I thought this could also represent human migration, and we shouldn't be big-headed enough to always treat homo sapiens differently from other species). It's well worth quoting conductor Ken Woods here:

In this piece, his meditation on the migrations of birds evokes both wonder and sorrow, and a profound mixture of connection and isolation. It's one of the most moving works I've come across, from any generation, in a long, long time, and you can see in the performance the depth of the players' emotional engagement with it as well.

Ken Woods discovered Williams' music fairly recently, spelling out what those of us close to him have known for some time:

I checked out his website, and within 24 hours I was convinced he was one of the finest composers of our time and I immediately asked him to succeed David [Matthews] at the ESO.

It's certainly time for Adrian Williams' music to become more widely known. Last night's concert is available to stream free-of-charge from the ESO website until Tuesday. After that, it's available with many other valuable ESO digital concerts via an ESO subscription.

Copyright © 12 June 2021

Keith Bramich,

London UK