- Hollywood

- Morton Feldman

- Sarah Frances Beamish

- Otello

- Simon Rattle

- Verbier

- Andrea Fages Saiz

- Kungsbacka Trio

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

SPONSORED: A Seasoned Champion of New Music. Argentinian-American pianist Mirian Conti in conversation with Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: A Seasoned Champion of New Music. Argentinian-American pianist Mirian Conti in conversation with Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

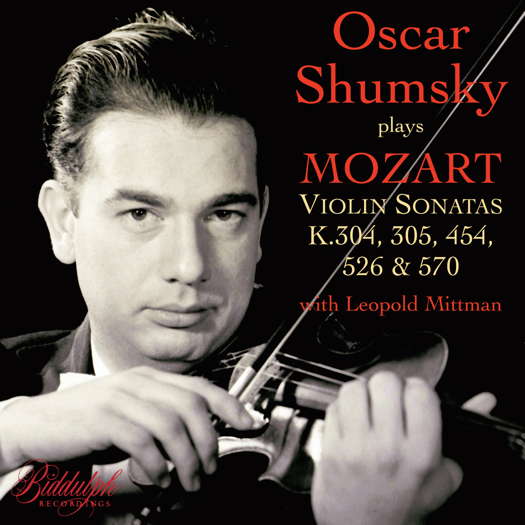

Magical Equilibrium

PATRICK MAXWELL listens to Mozart Violin Sonatas played by Oscar Shumsky and Leopold Mittman

'... a striking hold over tone and articulation ...'

The fact that Mozart's Violin Sonatas were one of Albert Einstein's first musical loves surely tells us enough about both the mind of the scientist and the pieces themselves. And it is not hard to see the attraction, the reasons why the both streaky yet refined genius of Mozart was so appealing to another man also searching for a different kind of order among chaos. Einstein said he often found solace in Mozart - inspiration, if we must - when lost in the abyss of his problems, and went to him for a reminder of the seeming simplicity with which Mozart managed to do what he did. There is not only the instinctive nature of this music, with the two parts caught in some magical equilibrium, but the equally powerful combination of the beauty of maths and the maths of beauty.

But that's enough highfalutin stuff for now; it doesn't particularly need the theory of relativity to show how great a composer Mozart was. This recording from 1951 takes a selection of the Violin Sonatas written at the peak of Mozart's productivity. The soloist Oscar Shumsky was one of the most renowned in his day, and the adulation he received for a striking hold over tone and articulation is fully justified here. Impressively accompanied by Leopold Mittman, the sound here is a distinctively twentieth-century one, with a clarity and direction which is somewhat replaced by the smoothness of tone and broad brush strokes of much modern playing; true as much with Mozart recordings as with Schubert ones.

Yet that should not diminish the exemplary standard of playing here, just as fresh as it was seventy years ago. The first Sonata, in the unusual key of E minor, starts with an equally unfamiliar sense of isolation which fades away as fast as it arrives.

Listen — Mozart: Allegro (Violin Sonata in E minor, K 304)

(track 1, 0:00-0:46) ℗ 2021 Biddulph Recordings :

Both players create a contrast between each phrase; each one has a specific identity within the piece, clearly set out by the dynamics and articulation. That the overall tonality and attentiveness of the pieces is brilliant almost goes without comment. The only hindrance to the sound quality is the age of this disc, which should never, with such music despite it, discourage anyone from buying it.

The Sonata No 22 in A major has a more immediately characteristic feel to it, brought out by the innate musicality of this pair, whether that's in the homophonic phrases of the major opening or the crescendos of the violin as it holds out over the building piano.

Listen — Mozart: Allegro di molto (Violin Sonata in A, K 305)

(track 3, 0:35-1:14) ℗ 2021 Biddulph Recordings :

More of a lilt and sensitivity is sometimes wanted however, as the more relentless sections of this piece come across as brusque when a more musical sense of the whole is needed.

The B flat major Sonata No 32 is the best loved of these works, and the one with the best history. Folklore has it that Mozart had a piano part, but had not got round to actually putting it on paper for the premiere, and merely played it 'from memory'. Emperor Joseph II, presumably at the front of the audience, noticed that the piece of paper Mozart placed at the piano seemed rather empty, and inquired, perhaps in jest, whether he could have the part after the performance. It was hastily arranged.

Listen — Mozart: Largo - Allegro (Violin Sonata in B flat, K 454)

(track 5, 0:00-0:50) ℗ 2021 Biddulph Recordings :

Einstein had it that 'one cannot conceive of any more perfect alternation between the two instruments than that of the first Allegro' when discussing this piece, and it is easy to ask who could disagree.

The majestic opening is followed by the various journeys through the keys, in this Sonata filled with the most constant sense of Mozartian rhythmic energy, as if any of the others were missing any. Barring any of the few stray notes, such an energy is given its full due, and the same applies to the incredible serenity of the second movement. This movement, although premised on a simple major melody, fills up with the quintessential polyphony of Mozart's texture, and Shumsky evokes a more sensitive feel than before to each phrase, backed up by the precious subtlety of Mittman's piano playing. The dream-like held notes of the violin in the minor section are masterfully played, as Mozart takes us into the world which feels much more like that of his later works.

Listen — Mozart: Andante (Violin Sonata in B flat, K 454)

(track 6, 2:50-3:45) ℗ 2021 Biddulph Recordings :

The Sonata No 35 in A major bears much of this maturity, with more of an impulsive and jaunty tone with it. The meditative middle movement again combines the different voices to its seemingly light texture, with a theme reminiscent of the Eighteenth Piano Sonata in its sprightly arpeggiated figures.

The arrangement of the Seventeenth Piano Sonata into a piece for two instruments does not always pay off; whether the new piece is intended as a duet or solo piece seems uncertain, as does the overall texture of voices, devoid of the right pianistic tone Mozart first intended. It is nevertheless carried off with both players' recognisable spirit and vitality.

This is a very individualistic recording of both players' styles and, at times, techniques. That both were masters of their instruments, fully in control of this music, is not open to much question. Whether it is so suited to the styles which have come after it certainly is, but that cannot diminish such musical stature as on show here. Shumsky's playing, not given the acclaim of his most illustrious contemporaries, certainly deserves the exploration of a great deal more listeners.

Copyright © 22 June 2021

Patrick Maxwell,

Oxford UK

CD INFORMATION: OSCAR SHUMSKY PLAYS MOZART