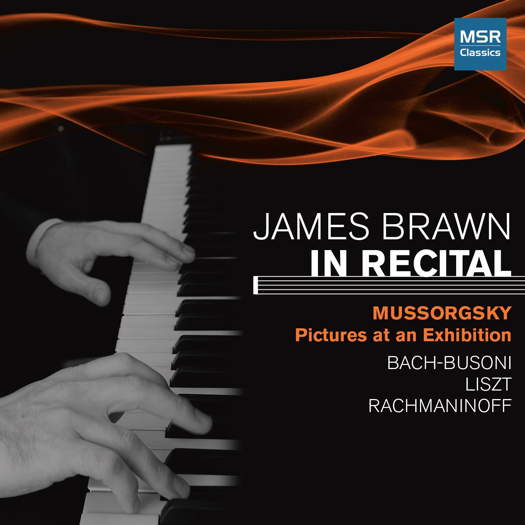

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. True Command - James Brawn plays Bach, Liszt, Musorgsky and Rachmaninov - recommended by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. True Command - James Brawn plays Bach, Liszt, Musorgsky and Rachmaninov - recommended by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

SPONSORED: An Integral Part - Lindsey Wallis looks forward to the Canadian Music Centre's tribute concert to composer Roberta Stephen.

SPONSORED: An Integral Part - Lindsey Wallis looks forward to the Canadian Music Centre's tribute concert to composer Roberta Stephen.

All sponsored features >>

- Andreas Nicolai Tarkmann

- Bent Lorentzen

- Dmitri Hvorostovsky

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Gerardo Guevara

- Lydia Griffiths

- Vladimir De Pachmann

- Friday Voices

Star Wars

GIUSEPPE PENNISI recommends listening to but not watching Maggio Musicale Fiorentino's production of Verdi's 'La forza del destino'

La forza del destino is not one of Verdi's most frequently staged operas. It requires at least six high-level voices - an 'absolute' soprano, a strong tenor, a baritone, a mezzo, a dramatic bass and a funny baritone-bass, plus quite a few secondary characters and dancers. It is the prototype of the 'grand opéra Po valley style' which had some success in the last decades of the nineteenth century in Northern Italy. It has a poorly credible libretto with a very cumbersome action that takes place between various parts of Spain and Italy in the war between Madrid and Vienna for the control of the Italian peninsula. There are two basic versions (and many interpolations): the first version dated 1862, composed for St Petersburg, is Byronian and desperately atheist; the second version, revised and adapted for La Scala in 1869, opens the door to faith and has a Manzoni style ending on forgiveness.

In the seven years between the two versions, Verdi had befriended Alessandro Manzoni; this explains the sense of doubt in front of the Highness - a feature of the 1869 edition. Finally, about La forza del destino there is the saying of it having bad luck for theatres and performers: a well-known baritone died on stage at the Metropolitan in New York while singing it and on other occasions several misadventures took place. In Parma at the 2001 Verdi Festival, for example, both the soprano and the tenor fell sick just before the opening night.

In the edition staged at the Festival del Maggio Musical Fiorentino, Philip Gossett's critical version of the 1869 Scala staging is used. All so-called 'tradition cuts' are opened, with the result that the show lasts about four hours, including intervals. There is a change asked for, it seems, by the stage director. The first duet between Don Alvaro and Don Carlo in St Petersburg was placed at the end of the third act, crowned by the tenor's cabaletta, while in Milan a soldiers' choir preceded it; in this production, it was moved to before the great ensemble with a loss of dramaturgical unity in Act III.

The staging of La forza del destino is always difficult: I saw one at New York Metropolitan Opera with, in the second act, Leonora dressed as a traveller in zouave pants and everything else was ridiculous. Among my memories, a very beautiful 1982 staging at the Rome Opera with scenes by the distinguished painter Renato Guttuso and set in the Spanish Civil War of 1936; it was shown at La Scala too. Why not revive this instead of searching novelty for - as the French say - épater le bourgeois?

In this new production, the already complicated story is set in a period of time between 1758 in Seville (Act I) and 3333 (Act IV), after a nuclear war that reduced humanity to the primitive state, so much so that the final duel between Don Carlo and Don Alvaro is fought by means of pre-historical clubs. Star Wars does not fit La forza del destino: the plot and libretto have enough problems in themselves. Despite the beautiful videos of Franc Aleu (which can be fine for a dozen operas), I would suggest to Carlus Padrissa and his closest associates a 'sabbatical year'. They would learn the link between music, libretto, and stage action and how to make singers act. Instead of keeping them in poses like those of operas staged in provincial theatres in the 1950s.

A scene from La Forza del Destino at Maggio Musicale Fiorentino

Fortunately, there are the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino forces and Zubin Mehta. The conducting is, in some respects innovative - it is the fifth production of La forza del destino that Mehta has conducted at Maggio Musicale and I have had the pleasure of enjoying a couple of them. In the symphony, the tempos are tight, but in the rest of the opera, they are dilated almost to make one perceive the depth of the opera's inspiring concepts (despite a rather mediocre libretto). Mehta never covers the singers but helps and supports them. He emphasizes the ability of groups of instruments: the horns were magnificent.

Zubin Mehta

This reminds us that the recurring theme is not a Wagnerian leitmotif but a magnificent Verdi mnemonic theme which anticipates developments in Don Carlos and especially in Aida. The chorus, prepared by Lorenzo Fratini, was superb, particularly at the end of Act II and in Act III. The audience responded to Mehta and Fratini not only with applause but with ovations.

As in Il Trovatore recently seen and heard in Rome - read Black and White, 17 June 2021 - among the protagonists, the women's voices were a few inches taller than the men's. Saioa Hernández debuts the role of Leonora with enviable security of the high register and good management of her centre register. She was very good in the Act I 'Me pellegrina ed orfana' and soaring in the Act II choral prayer; she showed a good dynamic in 'Pace mio Dio' in Act IV. She had a lot of open scene applause.

Roberto Aronica as Don Alvaro and Saioa Hernández as Leonora in La Forza del Destino at Maggio Musicale Fiorentino

Annalisa Stroppa is an all-round Preziosilla: soaring, seductive, mischievous, made almost like a prostitute - not a gypsy - with a slight Brechtian tone, and therefore a little sinister, in 'Viva la guerra'.

Annalisa Stroppa as Preziosilla in La Forza del Destino at Maggio Musicale Fiorentino

The Rataplan was dampened by the director's manipulation of Act III. I have listened to Roberto Aronica several times as Don Alvaro; he began almost faintly in the duet and scene of Act I. He intoned with fragrance 'Ho tu che in seno agli angeli' at the start of Act III but seems to have lost strength in the rest of the act, to take it back in the duet 'Invano, Alvaro' in Act IV.

In short, this was a mature but discontinuous performance. Amartuvshin Enkhbat, designated as the next Rigoletto at La Scala, has, without any doubt, imposing vocal means and a capacity for power and timbre but seemed to lack nuances, especially phrasing.

There are two big names in the roles, so to speak, secondary: Nicola Alaimo is an almost Donizettian Fra Melitone and Ferruccio Furlanetto a still imposing Padre Guardiano, despite having turned seventy-three. Both (especially Furlanetto) earned applause.

In short, this is a Forza del destino to listen to, without watching.

Copyright © 23 June 2021

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy

MORE ARTICLES ABOUT THE MAGGIO MUSICALE FIORENTINO