DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

- Rodolfo Saglimbeni

- Haydn: The Creation

- Cyril Rootham

- Vicki Field

- Walton: The Twelve

- Peter Gilbert

- Netherlands Beethoven Prize

- Japan Kapustin Association

A Philological Discovery

GIUSEPPE PENNISI writes about the seventeenth century Italian architect and global musician Carlo Rainaldi

Some ten years ago, Music & Vision magazine published a review of the first ever recording of music by a well-known seventeenth century Roman architect, Carlo Rainaldi (1611-1691) who, for his own pleasure, composed and played music too. (See 'Praise and attention', 21 September 2010.) Since then another CD of his music has been issued, and a third is on its way, to complete the cycle. More importantly, the Italian Institute of The History of Music is about to publish a volume that is, in fact, a discovery: the critical edition, by music critic and scholar of the Roman Baroque, Lorenzo Tozzi, of Rainaldi's cantatas. This is a musical world largely unknown as it was dealt with only in an article by the German musicologist Hans Joachim Marx back in 1969, then published in Italian in the Italian Journal of Musicology. The volume will also contain the two existing CDs containing part of Rainaldi's cantatas.

Rainaldi is in the hall of fame as a leading architect of the Roman Baroque, not as a musician. He is one of the six greatest architects of that time. To him, we owe, among other things, masterpieces such as the Church of Santa Maria in Portico in Campitelli (1633-1667).

The façade of Santa Maria in Campitelli

He also designed the façade of Sant'Andrea della Valle (1661-1665), the project of considerable value for two twin churches in Piazza del Popolo (1662-1675), projects for Sant'Agnese in Agone (where he was replaced by Francesco Borromini), the apse of Santa Maria Maggiore and the façade of the cathedral of Monte Compatri. In 1666, he took care of the design and construction of the Church of San Gregorio Magno in Monte Porzio Catone. There's also the Church of Suffrage in Via Giulia (1669-1675), the Spada Chapel at the New Church and the high altar in San Gerolamo della Carità. Also his work is the monumental tomb of Pope Clement IX, also in Santa Maria Maggiore. These works are studied in the major texts of architecture and they are also the object of pilgrimages by tourists visiting the Italian capital.

the interior of Santa Maria in Campitelli

Only a few experts, indeed erudite scholars, are aware of his musical activity. In the preface to the volume now in print, well-known architect Paolo Portoghesi writes:

It is not surprising that a sensitive and refined character cultivated, as a second love, that for music. Moreover, music offered him a means of personal approach to the world of nobility and the Papal Court that offered the architect precious opportunities for work. Documented is his familiarity with some of the great Roman families such as the Orsini, dukes of Bracciano, the Barberini, the Borghese, the Maidalchini and the Pamphili.

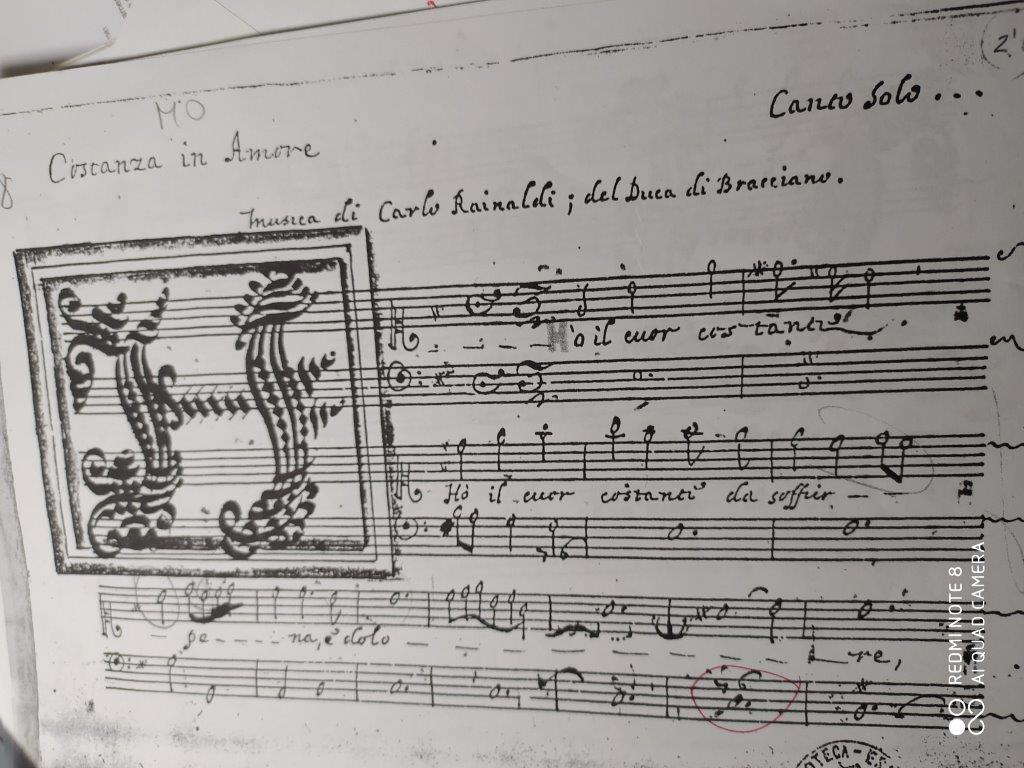

'Costanza in Amore', written for the Duke of Bracciano by Carlo Rainaldi

One of the instruments that Carlo Rainaldi played, in addition to the harp, the organ, the harpsichord and the lyre, was the mysterious rosidra invention of Paolo Giordano Orsini, Duke of Bracciano, an instrument of which we know nothing.

In Rainaldi's musical language stand out lyrical intonation, grace and vivacity, but also an inclination to admit dissonances that, in the context of the cantatas, foreshadow future developments of musical history. Portoghesi identifies affinities with Rainaldi's architectural language. From the intimate and sentimental intonation of the cantatas you can also grasp a reflection in his architecture for the intensity with which they address the observer 'opening up' towards him through forms of concave and convex curvatures that identify and favour an area of frontal use.

Very little is known about Rainaldi's life; there's not even an image of him. The insistence in the lyrics of the cantatas on love disappointments, punishments, disillusionments, the coincidence of love and suffering make one think of a celibacy full of love relationships; but perhaps it is a homage to a then prevailing style. Rainaldi, of course, operated in a globalized Rome from a cultural point of view: four of his cantatas are on texts by the British poet Patrick Carey, appropriately translated into Italian. These were the years in which Christina of Sweden (in exile from her Nordic Kingdom) had created a real international academy in Rome. This culminated in the construction of the first theatre open to the public. Rainaldi was probably part of the former Queen's entourage; one of his works - of sacred music and therefore not included in this edition - is in the Swedish language.

I talked about the critical edition with Lorenzo Tozzi who edited it. He commented :

The choice of texts puts wings to Rainaldi's compositional fantasy: they are baroque texts with pathetic images, often metaphorical, but easy to read beyond the humanistic and archaic mythological curtain. A prominent element is the tonal consistency between the different components of the cantatas. Rainaldi's predilection for some poets is clear. In only about a third of Rainaldi's cantatas, the name of the author of the poetic text is indicated. They are eg Francesco Melosio for E chi mel crederà and the duet Vaghi rai, pupille ardenti, Carlo Eustachio for Uccidetemi pur, fieri tormenti, Giorgio Giustiniani for the duet Che di dici, Amore?, Mario Cevoli for Deh, lasciatemi in preda al mio tormento and Patrick Carey for Non replicarmi, Amor, Con lusinghe di sirena, Dì, mio cor e Pupillette, ben avvede.

No wonder that certain harmonic licenses are often dictated by expressive purposes. Neither the lack of instrumentation because the practice of basso continuo was then consolidated. Interesting features are the anticipation of delays, the not high extension of acute voices, certain residues of 'madrigalisms' in the writing corresponding to certain words, simple melodic underlining, in lieu of bel canto, indications of instrumental refrains. In addition, the cantatas are identified with the incipit, never with the chosen form - madrigal, song, air or the like. In the strophic variations, in which singing and bass remain the same but the lyrics are different, the second verse is not transcribed musically in full, but only annotated for the poetic part. When the second stanza is written in full, this offers interesting documentation on the art of seventeenth century variations. It should also be noted that in general the cantatas were written by musicians or at most by celebrated singers, but Rainaldi dedicated himself to it in the rare spaces of time granted to him by the many commitments he had as an architect. For him, therefore, music was leisure, but it could serve to create new important contacts and to make himself even more appreciated by the noble Roman patrons.

Lorenzo Tozzi

In Rainaldi's cantatas, the dominant theme is that of a contrasted or unreciprocated love. There is a certain indeterminacy, both tonal and modal, but above all in some places a more contrapuntal-horizontal than harmonic-vertical mentality being the most melodically plausible musical discourse that can sometimes be justified harmonically.

A discovery, therefore, to be savoured by all.

Copyright © 24 January 2021

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy

MORE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY MUSIC ARTICLES

MORE CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT ITALY

FURTHER INTERVIEWS, PROFILES AND TRIBUTES