DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

- piano trio

- Bru Zane

- operetta

- La forza del destino

- Akustiikka

- Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Negro Melodies

- Ian Stephens: Springhead Echoes

- Sidney Marquez Boquiren: Five Prayers of Hope

RESOUNDING ECHOES: Beginning in 2022, Robert McCarney's occasional series features little-known twentieth century classical composers.

RESOUNDING ECHOES: Beginning in 2022, Robert McCarney's occasional series features little-known twentieth century classical composers.

Sheer Contrast

Prokofiev and Beethoven symphonies from

the Hallé Orchestra and Mark Elder,

impressing MIKE WHEELER

Prokofiev's and Beethoven's last symphonies might seem to have little else in common, but it was a pairing that worked by sheer contrast.

Prokofiev's Seventh used to be regarded as a bit of a let-down after Nos 5 and 6. But it's more than just a light-weight piece of fluff, as the Hallé Orchestra and conductor Sir Mark Elder made clear right from the start, investing the arching melodic lines of the opening with both poignant lyricism and tensile strength - Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, UK, 29 February 2020. There was an agreeable transparency to the sound with, contrary to the orchestra's usual practice these days, the second violins seated next to the firsts, and the violas front-right. (They reverted to their usual seating, with seconds on the right, for the Beethoven.)

After its hesitant opening the second movement waltz, parts of which wouldn't sound out of place in Prokofiev's Cinderella, went with a swing. The spikier moments were given their due as well, conjuring up all sorts of imps and gargoyles. There was real poignancy in the third movement, and breath-stopping magic in the soft shimmering close, for which harpist Marie Leenhardt deserves much of the credit.

Marie Leenhardt, the Hallé Orchestra's

Principal Harpist. Photo © 2016 Peter Warren

The finale made its entrance like an exuberantly high-kicking chorus line, and the bouncy comic march later had plenty of spring in its heels. The return of the big tune from the first movement was given space to expand, and the wry, ticking figure from the end of the movement - Mark Elder's spoken introduction referred to this as 'fairy-tale, castles in the air' music - that also reappeared, was allowed make its statement without undue emphasis. Rightly, we got the original quiet ending, without the fast half-minute that Prokofiev added later.

Some like Beethoven's Ninth to open in a haze of mystery. I prefer it charged with rhythmic definition, however quiet, and that's what we got after the interval. Buzzing with activity from the word go, it launched a performance marked by, on the whole, brisk tempi but still with a sense of the work's epic scale. Elder was clearly playing the long game, keeping power in reserve, constantly looking forward to the next big moment. The recapitulation, when it came, blazed like a supernova.

In the middle two movements, orchestra and conductor eased off the emotional pressure without letting the momentum slip. The Scherzo was athletic, Beethoven's artful silences full of expectation, and the trio section airy.

I became aware as never before of how much Mahler owed to the third movement, and of the echoes of Beethoven's own 'Pastoral' symphony - the violins' descant in the later variations recalling the Pastoral's brook, and with suggestions of the Shepherds' Thanksgiving elsewhere. The big fanfare-like passage felt aptly strange and monolithic.

The horns were allowed to cut through the savage outburst that begins the finale, giving it extra bite. There was a genuinely vocal feel to the phrasing in the cello and bass recitatives that followed, and as the strings gently crooned the well-known tune, the bassoons' descant was a delight. (Beethoven's bassoon writing is always worth paying attention to.)

Come the vocal section, bass Neal Davies made his opening 'O, Freunde' - 'Not these sounds, let's sing something more pleasant and agreeable' - not hectoring, more like friendly encouragement. The 'Turkish' episode was brisk, though tenor Stuart Jackson sounded slightly underpowered from where I was sitting. Elizabeth Atherton's clear, gleaming soprano and Sarah Castle's warm mezzo completed the quartet.

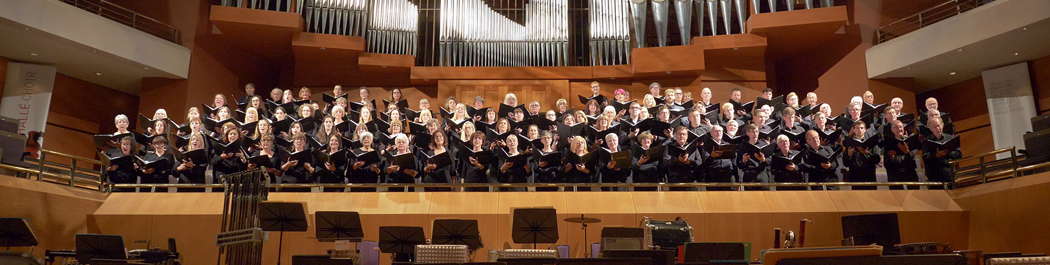

In many ways the members of Hallé Choir were the stars of the show, singing from memory, as the CBSO Chorus did here some years ago, and with just as much impact, and holding the big double fugue steady without losing impetus; the sopranos held their sustained top A with no sign of either strain or flagging. And they gave the more intimate moments a nice feeling of expectation.

The Hallé Choir in Manchester in 2019

There were moments when I felt I was listening to parts of this work properly for the first time, and you can't ask more of a performance of it than that.

Copyright © 9 March 2020

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: SERGEI PROKOFIEV

FURTHER INFORMATION: LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN