- North Korea

- Aurèle Nicolet

- Elijah

- Gloucester

- Los Angeles Opera

- Gerd Albrecht

- Lester Lynch

- Edward Nesbit: Wycliffe Carols

Back to the Future

GIUSEPPE PENNISI attends a gala evening in Rome

dedicated to two experimental works

Whilst La Scala opened its September through November season with a traditional and quite old-fashioned Rigoletto - read 'A Star is Born', 7 September 2019 - Teatro dell'Opera di Roma began its Autumn program on 10 September 2019 with a Gala evening dedicated to two experimental works. It was a special occasion. Tickets were not sold at the box office, as usual; they were, instead, given to those who had donated at least 200 euros to a foundation. The other five performances of the double bill are available at regular prices. In addition, during the intermission, sparkling white Italian wine was offered to the audience. The house was full, with the exception of the upper tier which, in practice, was not operative.

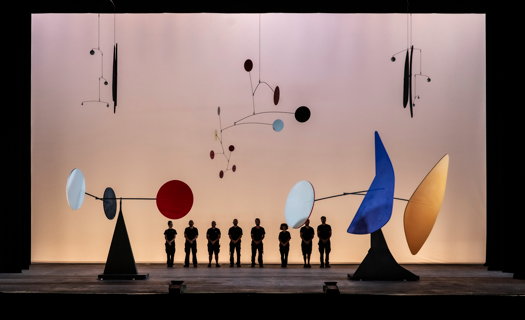

The double bill was titled Calder/Kentridge after two visual art artists, not musicians or their works. The first of two single-act works performed is Work in Progress - a theatrical images show created in 1968 by American scultptor Alexander Calder (1898-1976) on taped electronic music by Niccolò Castiglioni, Aldo Clementi and Bruno Maderna - three prominent composers of European experimental music at the time.

A scene from Alexander Calder's Work in Progress at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Yasuko Kageyama

Work in Progress is a theatrical occasion : the projection to the stage of a poetical fantasy in which the creations of one of the most important sculptors of the twentieth century, Alexander Calder (who calls his sculptures 'objects'), move and function to the electronic music of the time. There are neither singers nor actors on stage, but only a few mimes (and a moment of a fascinating bicycle ride). There is action: by the 'mobiles' - Calder's well known approach to sculpture - and by the design on painted drop sets. The visual part is, of course, abstract and perfectly in line with the composite and well-moulded electronic score. Together, they intend to recreate the infinity of the universe. The performance lasts about twenty minutes. The audience was very attentive and exploded in long ovations.

A scene from Alexander Calder's Work in Progress at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Yasuko Kageyama

Since 1968, as far as I know, Work in Progress has been revived by Teatro dell'Opera only once, in 1983 (when I saw and heard it as a part of a program of contemporary music). The stage director was Filippo Crivelli, now ninety years old, but still very active in drama and opera staging. He was the director now as in 1968 and in 1983. Teatro dell'Opera has a copyright on Work in Progress, which has been performed only in Rome so far. Staging it is, of course, a difficult enterprise. It may be useful to provide a high definition DVD, for showing it also on television channels especially dedicated to classical music, because it is a real joy for both the eyes and the ears.

A scene from Alexander Calder's Work in Progress at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Yasuko Kageyama

The second work is the world premiere of a special one-act opera, Waiting for the Sibyl, created by South African visual artist William Kentridge (born 1955) on music composed and elaborated by two South African musicians, Nhlanhala Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd. It is a commission by Teatro dell'Opera di Roma as well by the Swedish Royal Dramatic Theatre and by Luxembourg's Théâtre de La Ville.

William Kentridge, rehearsing Waiting for the Sibyl at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Stella Olivier

Thus, the double bill looks at experimental theatre and music: both in the late 1960s and now (or rather in the future, because South Africa is anticipating some American and European trends). So in a sense, a look at the past, to better grasp what is coming.

A scene from William Kentridge's Waiting for the Sibyl at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Stella Olivier

Waiting for the Sibyl is a fifty-minute opera based on the Sybil's myth, as described in Dante's Paradiso. There is no plot and the central character, the Sibyl, is a dancer. Those who want to know their future go to the Cumaean Sibyl, who writes her predictions on oak leaves. In Paradiso, the leaves are blown in a circle around the Sibyl and, collected by the wind, turn into the pages of Dante's book. In Kentridge's opera, the leaves are blown too, but the Sibyl's clients can catch them. They remain unsatisfied, however, because, intimately, they long for something more than a machine - the modern Sibyl is an algorithm - to guide them on how they see, and mould, their future. The apologue is engrossing mainly because of Kentridge's staging - sets and design - and the very intense score by Nhlanhala Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd. On stage, South African singers and dancers perform, sing and play, but part of the music - the piano score - is taped. It is tonal music, alternating between a strong rhythm and a melodious adagio, as well as with African traditional songs.

A scene from William Kentridge's Waiting for the Sibyl at Teatro dell'Opera di Roma. Photo © 2019 Stella Olivier

It was warmly applauded. I trust that success will accompany this new and original opera in Stockholm and Luxembourg as well as on a world tour now being finalized.

Copyright © 12 September 2019

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy