- Sir Colin Davis

- Charles Kennaway

- Hector Berlioz

- Ferris

- Robert Starer

- Quebec

- Shaker melodies

- Britten: The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Pure Magic - James Brawn's continued Beethoven Odyssey, awaited by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Pure Magic - James Brawn's continued Beethoven Odyssey, awaited by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

Fierce Commitment

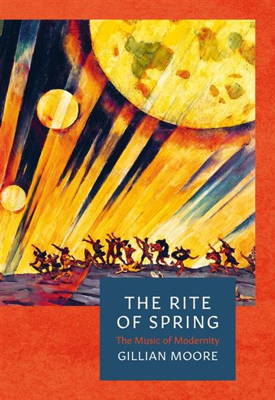

Gillian Moore talks about her book

'The Rite of Spring. The Music of Modernity'

and then Philip Moore and Hugh Watkins play

Stravinsky's 'Le sacre du printemps',

preceded by John Adams' 'Hallelujah Junction',

all reviewed by MIKE WHEELER

The strand of literary talks at the Buxton Festival this year included Gillian Moore, Director of Music at London's Southbank Centre, talking us through her recently-published book on The Rite of Spring, illustrating her musical points with recorded excerpts and on the piano - Pavilion Arts Centre, Buxton, UK, 8 July 2019.

She confessed that she found it intimidating to write about at first, not least because of her feminist side reacting against the idea of a female sacrifice to the god of Spring. It also meant working her way through the huge amount of previous literature on the work - what she disarmingly described as 'twenty times my body-weight of scholarship'.

Setting the work in its wider contemporary context, she invoked cubism, poet Gertrude Stein, the publication of Volume 1 of Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu, and the paintings of Sonia Delaunay. In addition, 1913, the year of The Rite's premiere, was, she pointed out, 'the year modern art reached New York'. Italian futurist Luigi Russolo was exploring the art of noise, and the first Model Ts were rolling off Henry Ford's production line, suggesting an industrial, mechanised aspect to the The Rite's rhythmic organisation.

Sketching in its cultural-historical background, Moore took us from Peter the Great's westernising influence in the early eighteenth century to the eventual counter-moves in literature and painting, and in music, principally through the group of composers known as The Five. Dyaghilev inherited all this, creating a craze for Russian culture in Paris in the few years before The Rite's premiere, promoting concerts of Russian music, and staging Borodin's opera Prince Igor.

Accounts of The Rite of Spring's origins differ, with Stravinsky's well-known claim to have had an initial vision of what became the final scene apparently contradicted by stage designer and expert on Russian pre-history Nikolay Roerich's recollection of what seems to have amounted to little more than a committee meeting between him, Stravinsky and Dyaghilev.

Moore then considered what was new about the work, choreography as well as music. Stravinsky's handling of his large orchestra, treating it in places like a huge percussion instrument, and in his foregrounding of rhythm, were two aspects singled out by composer George Benjamin, quoted by Moore as she later considered the work's far-reaching influence, what she termed the 'aftershocks'. The dancers not only found the music's complexity bewildering, but Nijinsky's choreography went against everything they had been trained to do, demanding they direct their energies downwards instead of upwards.

Among the 'aftershocks', Moore drew our attention to a range of music, from Varèse's Amériques, through jazz and popular music luminaries such as Ornette Coleman, Joni Mitchell, Frank Zappa and Alice Coltrane, to The Rite's palpable influence on film scores including Psycho, Jaws and the first Star Wars film. She ended with a brief consideration of recent work by choreographers looking for new ways of presenting the work.

Moore's book The Rite of Spring. The Music of Modernity compresses a huge amount of information, illustration and shrewd judgement into its modest size. The author gave us a substantial taster, charged with her obviously still undimmed enthusiasm for the piece.

The Rite of Spring. The Music of Modernity by Gillian Moore, Head of Zeus Ltd, 2019, ISBN 9 781786 696823

Following an hour's break, Philip Moore and Huw Watkins were on stage to play The Rite in a version for two pianos.

They prefaced it with a more recent work with quite a few Stravinskian echoes, John Adams' Hallelujah Junction, bringing out the first section's rhythmic affinities, along with its shifting colours and textures, and giving an edge to the abrupt staccato writing as they bounced material backwards and forwards between them. In the second section they played with the gentle skipping figure that emerges from more flowing music. As metrical shifts start making themselves felt, Moore and Watkins allowed Adams' humorous side to come through, and navigated a passage of extraordinary harmonic complexity as it drew to an end.

Buxton Opera House and Pavilion Arts Centre online publicity for Philip Moore and Hugh Watkins' recital

The gains and losses in versions of The Rite on the piano don't just concern orchestral colour in itself. That celebrated opening sounds weird and unearthly as originally scored for solo bassoon, but there is simply no point on a piano keyboard where it can project a comparable sense of strain. But as Stravinsky builds his opening nature-music mosaic, Moore and Watkins threaded their way clearly through the accumulating layers, keeping a tight rein on the pounding rhythms of 'Auguries of Spring', with fierce stabbing accents from Watkins as a one-man horn section. 'Spring Rounds' sounded unexpectedly stark in this form, but the sheer density of the rhythmic layers in 'Sage's Cortege' were as lucid as we had any right to expect, while the Sage planting a kiss on the earth was a moment of stillness every bit as eerie as in its orchestral guise. The Introduction to Part 2 was invested with a mesmerising sense of expectation. Moore and Watkins juggled the demands of the culminating 'Sacrificial Dance' - differentiating the elements of texture while allowing the repetitiveness to accumulate tension - with fierce commitment.

Copyright © 27 July 2019

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK

REVIEW OF GILLIAN MOORE'S BOOK 'THE RITE OF SPRING'