- Parry

- Wellington

- Gerald Finley

- New Jersey Pro Arte Chorale

- George Dannatt

- Salieri: Piano Concerto in B flat

- Minnesota University

- Jenni Brandon

A MULTI-ART EXTRAVAGANZA

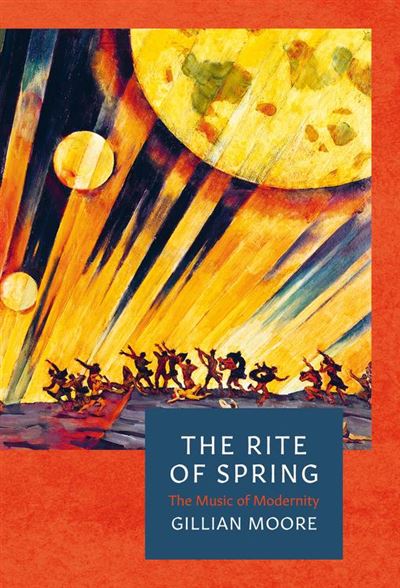

RON BIERMAN reads Gillian Moore's

'The Rite of Spring, the Music of Modernity'

'It is one of the most documented artistic events of all time' writes Gillian Moore. But Moore's addition to the literature about the 1913 blastoff of The Rite of Spring is welcome nonetheless. Though only 208 pages long, it's a more complete picture than usual, written in a clear style, with useful references and footnotes. The handsome, artfully done book includes many photos and colorful images to add to the pleasure of reading. They include a black and white photo of Stravinsky and his wife Vera with Jackie and John F Kennedy, color sketches of costumes designed by Nicholas Roerich for The Rite of Spring, and pages of the score in the composer's handwriting.

Moore begins with a brief biographical sketch of Stravinsky and the effect renewed Russian interest in the country's folk culture had on his music. She follows this with a description of the composer's collaborators and how The Rite of Spring came to be written. The stage is thus set for the premiere itself, the story the ballet and music tell, and the musical structure and orchestration Stravinsky chose for the piece. The concluding chapter sketches the ripples from the 1913 premiere still being felt today.

In an era of bubbling change and creativity, the music world was already abuzz over the daring departures of Schoenberg and Debussy. Painting and literature were alive with similar startling breaks with tradition. Diaghilev, well respected by Russia's modern artists, first attracted notice outside of Russia with a Paris exhibition of their paintings and sculptures. Effective showman that he was, he seized an opportunity to combine French society's craze for all things Russian with the prevalent thirst for the sensationally different in multiple arts. His Ballets Russes was the hugely successful result. It combined modern ballet with colorful sets and costumes by successful contemporary artists, and avant-garde music by audacious young composers such as Stravinsky, Prokofiev and Satie.

And so, although The Rite of Spring survives primarily as a concert piece, its premiere was a multi-art extravaganza designed by Diaghilev to be a magnet for publicity. Nijinsky, the best known male dancer of the early twentieth century, choreographed steps very unlike those of traditional ballet, and Nicholas Roerich, a Russian painter and writer who had had colorfully flamboyant successes in Russia and Paris, designed both sets and costumes. Stravinsky had already stunned the music world with The Firebird and Petrushka for earlier Ballets Russes productions. Rite solidified his reputation for startling invention and, depending on which critic you believed, his fame or notoriety.

Supporters and members of Ballets Russes in 1911, including Vaslav Nijinski (fourth from left), Igor Stravinsky (fifth from left) and Sergei Diaghilev (second from right)

Diaghilev ensured attention with open rehearsals to which he invited selected critics, musicians and writers. There is no doubt the following premiere caused a sensation, but for all that's been written about audience reaction on that night, what has been reported depends on who was doing the remembering. Was the commotion a riot that stopped the music and required gendarme intervention? Some of those who wrote yes with authority weren't even there, and the concert in fact continued after The Rite of Spring with two additional, non-controversial ballets. Nijinsky starred in these after having been backstage during the premiere, beating time for the dancers when he knew the noise was drowning out the orchestra.

Ballets Russes (1912, painting, oil on cardboard) by August Macke (1887-1914)

Moore does an excellent job of sifting through newspaper reports and other written descriptions of the evening, choosing some of the most striking accounts. She quotes writer Carl van Vechten as saying a young man at one point stood behind him so excited by the music that, 'He began beating rhythmically on my head with his fists. My own emotion was so great that I did not feel the blows for some time.'

We'll never know if that was a bit of an exaggeration, but over a hundred years later at a performance of the now familiar piece by the San Diego Symphony Orchestra led by Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, I was myself so lost in the savage fury of some passages that I'm not sure I would have noticed someone behind me following in the head pounding tradition. (As an aside, I happened to speak with a conductor a few weeks after the performance who complained Mirga, as she may someday be known, wasn't entirely accurate in the work's complex rhythms, which may well have been true, but perhaps beside the point?)

Stravinsky's score is often cited as the reason for boisterous jeers; Nijinsky's choreography may have been a bigger factor. Dance movements were meant to help establish an atmosphere of primitive pagan abandon. Stravinsky said the storm broke, 'When the curtain opened on the group of knock-kneed and long-braided Lolitas jumping up and down'.

Igor Stravinsky

Unsurprisingly, since its premiere The Rite of Spring has influenced the work of many classical composers. Prokofiev, Varese and Antheil, as cited by Moore, were among the first to write pieces that made use of similar harmonic and rhythmic effects. Her chapter also discusses less expected aftershocks. A screen shot from Disney's Fantasia, a photo of rock musician Frank Zappa and another of jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker help make the point.

Today it's impossible to imagine a ballet, no matter how radical and outrageous, that would get even a peep out of today's staid, respectful audiences. Displeasure is expressed by the absence of a standing ovation amidst polite applause when the performance ends. Moore recalls a time when audiences for ballet, opera and classical music felt free to become more visibly involved in a performance. It's a time worth remembering, and Gillian Moore, award winner and Director of Music at the Southbank Centre, describes it well.

Copyright © 17 April 2019

Ron Bierman,

San Diego, USA