CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

CENTRAL ENGLAND: Mike Wheeler's concert reviews from Nottingham and Derbyshire feature high profile artists on the UK circuit - often quite early on their tours.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

- Francisco Savín

- Carlos Cipa

- Nikolai Tcherepnin

- Peter Sculthorpe

- Gabriel Jackson

- Vato Klemera: Yours and Mine

- Mozart: Variations on 'Ah vous dirai-je Maman'

- David Wright

Roads of Genius

MIKE WHEELER listens to

Bohuslav Martinů's Fourth Symphony

Bohuslav Martinů's Fourth Symphony

Stephen Johnson's latest 'Discovering Music' event with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, with John Storgårds the conductor on this occasion, focused on Martinů's Fourth Symphony - Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, UK, 22 March 2019.

Inevitably the remarkable circumstances of the composer's childhood, born and growing up in a flat in a church tower (where his father was sexton and firewatcher) was our starting-point. The 'amazing views' of the surrounding countryside this gave him fed, in time, into his enjoyment of country walks, and Johnson linked this to William Blake's 'Improvement makes strait roads, but the crooked roads without Improvement, are roads of Genius.'

He went on to describe the make-up of Martinů's orchestra for this symphony - 'top-heavy' with upper woodwind, giving plenty of scope for mimicking birdsong, together with his characteristic use of the piano, and the influence of the jazz harmonies that he had enjoyed since his years in Paris. Johnson quoted a friend's description of the opening as 'a great crescendo of happiness', pointed out the 'pulse of life' sounds in the texture, and drew our attention to the 'awestruck' moment when the music suddenly becomes quiet and still.

Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) as a child, playing the violin, circa 1896

The piano 'springs centre-stage' for the second movement, darker but full of rhythmic inventiveness, while the more lyrical Trio section, Johnson suggested, is a tribute to Martinů's great predecessor, Dvořák.

The third movement is remarkable, he said, for 'the way Martinů controls light and shade'. He drew our attention to the 'ravishing transformation' in the passage where two solo violins and a cello add their own strands to the texture, plausibly making a connection with Vaughan Williams' Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. He could also have pointed to a link to the baroque concerto grosso. Martinů once described himself as a 'concerto grosso type', and the solo group here echoes the typical concertino ensemble in concertos by, say, Corelli and Handel. The music's key, B flat, was, Johnson said, the composer's 'key of hope and triumph', and the coda he described as 'transcendent'.

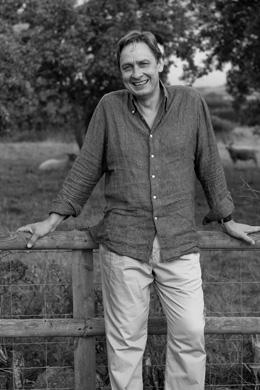

Stephen Johnson

After three movements in some form of triple time, the finale sees a switch to 4/4 time 'at last'. A 'sense of mounting strife' underlies the music, but the symphony ends with at least the 'possibility of joy.'

The complete performance, after the interval, was prefaced by an early Martinů work, Dream of the Past. A pity we weren't give any information about it, especially as the work-list accompanying the Grove Online entry on the composer tantalisingly lists it as incomplete. From its quiet, sombre opening, it moves to a flute solo with clear echoes of Debussy's Prélude à l'Après-midi d'un Faune. Later passages include some curiously Sibelius-like string writing, and a striking episode for cor anglais and lower strings. The clamorous build-up to the main climax was firmly controlled.

The BBC Philharmonic

The Symphony itself opened in a pertly boisterous mood, full of chattering woodwind, and a keen sense of rhythmic edginess. The start of the second movement was infectiously bouncy, with the two bassoons chortling away as only bassoons can. As it proceeded, the rhythmic drive was playful one moment, shot through with a menace worthy of Shostakovich the next. The Trio - unusually for a mid-twentieth-century symphony, it is actually marked as such in the score - was calmer and brighter, but always those active textures were kept full of vitality.

Nottingham Royal Concert Hall's online publicity for the Discovering Martinů concert, featuring the Finnish violinist and conductor John Storgårds (born 1963)

John Storgårds and the BBC Philharmonic brought an expansively song-like feel to the third movement, particularly in the string writing, and ensured a gripping approach to the central climax. The finale caught the celebratory tone alongside an awareness of the music's shadows. If the Fourth is Martinů's 'pastoral' symphony, as has been suggested (though not on this occasion), his country roads occasionally harbour some darker things.

Bohuslav Martinů in New York, 1945

With Opera North recently announcing a production of his last opera, The Greek Passion, in the autumn, it's good to see Martinů receiving increasing attention.

Derby UK