UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

A PERFECT FOOL

GEORGE COLERICK discusses Gustav Holst and his Richard Wagner parody

During World War I, Gustav Holst used to encourage his students to compose parodies, especially when classes had to retire to Morley College's air-raid shelter. For him, they were extensions of his researches into the music of other times and cultures; one of the reasons for the popularity of his Planets is that for once, he took opportunities to parody appealing composers of recent times.

As a young man, he had been a Wagner enthusiast, and in his maturity, wrote a sophisticated parody of his operatic style and that of Verdi. The Perfect Fool introduces magic, love potions and an absurd figure whose very insensitivity eventually gives him status. The Wagnerian allusions include Wotan, the god disguised in one opera as an earthly wanderer, his daughter, Brünnhilde, whom for disobedience he encased in a protective ring of fire, and her heroic lover, Siegfried.

In Richard Wagner's 'Der Ring des Nibelungen' and in Norse mythology, Siegfried awakens Brunhilde. Engraving by R Bong of original artwork by Otto Donner von Richter (1828-1911)

This is a tale of inadequate characters involved in a relentless sequence of anti-climaxes, and a peasant cunning enough to promote her indolent, half-witted son. Stereotypes take centre ground, with a contest for a Princess involving two self-styled operatic heroes and a wizard who can't produce even a little black magic on time.

Aion (or Uranus), the God of Eternity, with Terra (the Greek God Gaia), depicted in a section from a mosaic in Sassoferrato, Italy. According to Music Sales Classical's programme notes for 'The Perfect Fool', the wizard is obviously related to 'Uranus the Magician' from Holst's 'The Planets' Suite.

There is a melodramatic orchestral introduction, with the wizard conjuring the Spirits of Earth and Air to provide a cup filled with the essence of love distilled, whilst the Spirits of Fire shall dwell within it. By boasting how this magic will gain him possession of the Princess, he sets off events which will bring to an end his appalling existence. The listener is a poor Woman whose son has been the subject of a prophecy, that one day the intensity of his gaze will win a bride and kill a foe.

The first page of the full score for Holst's ballet music from The Perfect Fool, showing the opening trombone invocation representing the wizard summoning the Earth Spirits

It is said that all who look at the Princess fall in love, so this pathological villain intends to kill at a glance every man he meets. Fortunately, he considers all females witless and beneath contempt, so on meeting this one, he merely demands unquestioning servitude after demonstrating power over her. He orders her to teach him the courtesy necessary for wooing, then he acts out with her the courtship of the Princess. His singing of a 'prize song' is not his best effort because he is saving all his magic for the big day. Like Beckmesser in The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, he is absurdly over-confident, promptly blaming the woman:

But why are you so stiff? That's the great point of the song and you've missed it. We must go back and do it properly ... You're the worst actress I've ever met: no feeling, no imagination, no sense of style.

(Note: Beckmesser was a bad critic but a worse singer. He attempted to steal a song prepared for the Mastersingers' competition, but landed a spoof version, and sang it, only to earn the ridicule of the whole town.)

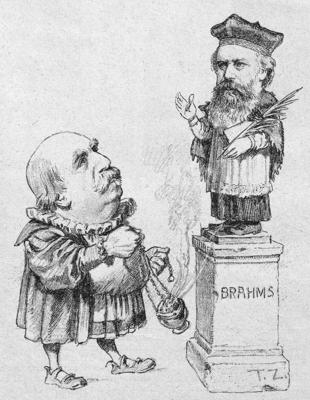

An 1890 cartoon from the Viennese satirical magazine Figaro showing music critic Eduard Hanslick offering incense to Johannes Brahms. Hanslick was known to praise Brahms' music but to have a low opinion of Wagner's output. Wagner probably took his revenge by basing the Beckmesser character in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg on Hanslick himself.

Now he needs her even more so, proposing she should be a surrogate wife (not a romantic figure in opera), and falls asleep confident that she will watch over him like a good fairy. So all she has to do is conceal her son, and steal the potion, replacing it with pure water which she praises in an ode of surprising delicacy. The Fool is duly instructed to drink the potent brew.

The Princess arrives with a splendid cortège, confident this is the day she will choose her husband, who will be the bravest of all, capable of an act no other can achieve. The wizard offers himself as the first suitor, but he is greeted by the assembled ladies with ridicule, mainly because he is too old and ugly, according to the Princess who does not mince her words.

He is not discouraged because he will be rejuvenated, and starts his serenade which has such a discordant note that the Princess calls for help. Deflated that the drink has not done the trick, the wizard retires with threats that he will wreak vengeance on the entire community.

The next suitor is an Italian Troubadour who woos the Princess with a melody reminiscent of Arthur Sullivan out of the drinking song from Traviata. His attempts to bring gaiety to the scene show that he is just one more boastful suitor. With such posturing, he provokes the Princess to compete against his high notes, but she beats him hands down and with a final flourish of rich coloratura, he is unceremoniously given the push. As prize songs go, the Troubadour's must be the one most rapidly and melodiously seen off.

Italian singing by the 'twenties hardly needed further burlesquing in Britain, but on this occasion the performance of an ineffectual Troubadour throws the ponderous Germanic music which follows into amusing contrast. Its heavy orchestral chromaticism descends into appalling gloom, then instead of a youthful tenor voice, a bass, more Wotan than Siegfried, is heard from the self-styled Traveller. In singing of his 'bride to be', he confidently uses familiar Wagnerian phrases, but all to no effect. He then drifts towards Tristanesque despair, a theme from Act III no less. Does he enjoy suffering, or is he, like Wotan, too old for the ecstasy of love? Either way, this Princess has no time for niceties and crushes him with a few words: 'Sir, I think we have heard this before.'

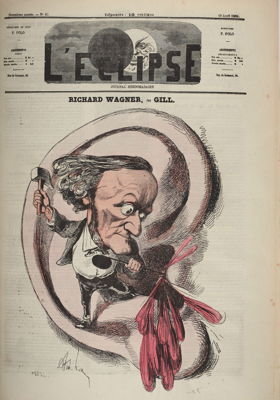

A hand-coloured engraving by André Gill, published as the front cover of the French magazine L'Eclipse, dated 18 April 1869, using a caricature of Richard Wagner to suggest that his music was ear-splitting

The Traveller exits to music from The Twilight of the Gods. This is the moment for Wotan to ensure that the Princess sees her son, and in no time at all the cortège is wailing that she has fallen for a beggar. Against this new threat, the suitors protest, drawing encouragement from more Wagner and a snatch of the sexual catalogue from Don Giovanni.

Terrified by the news that the wizard has set fire to the district, the courtiers flee, leaving the Princess to face him, but serenely she sings of her indifference to earthly dangers. Directed by his mother, the Fool's glance is targeted at the wizard who is consumed by fire. The Fool must be the most inept hero in opera, but the Princess implores his eternal love with some very high operatic notes indeed. He responds with an expressionless 'NO'!!!

This is his unique vocal contribution to the whole text. The mother and the chorus celebrate, repeating time again that he has performed the impossible by not falling in love with the Princess. A single note, on full orchestra, matches the Fool - the final anti-climax.

The wizard's music, and what represents the magic fire, is rhythmically most inventive, with an intriguing seven beats to the bar section, and it forms the outer movements of a ballet suite, an orchestral tour de force, far better known than the complete opera. The middle section has ethereal music associated with the Princess's search for love.

A royal bride should be the most popular of operatic clichés, but one who neither gets her man nor dies of grief is an outsider. This one is not endowed with immense charm, or seemingly much imagination, but the ironies of the story did not satisfy The Perfect Fool's first audience. They had not expected one which broke so many conventions and just faded out. Was it incomprehensively 'modern' or just a joke? Holst was not trendy but very committed and consistently adventurous in his choice of themes.

Portrait by Herbert Lambert (1881-1936) of Gustav Holst, circa 1921, around the time that he composed The Perfect Fool

Successful Wagner parodies are scarce and the work is unique; apart from that and the Italian episodes, the rest of the music suggests that this magical realm lies within the British Isles. Considering the English social scene of the 'twenties, an amusing explanation of the plot was offered by musicologist Sir Donald Tovey, that the Princess represents Opera, and the Fool the British public.

Holst lived at The Manze in Thaxted, Essex, England from 1917 until 1925. He wrote The Perfect Fool between 1918 and 1922.

If the work had appeared some fifty years later, it would have been thought in part as an assertion of feminine superiority, an interpretation which would not have displeased the composer.

London UK